Provisioning the Corps

Portable Soup

Historical interpretation by John W. Fisher. Photo © 2018 Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

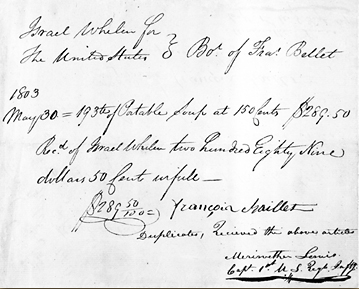

On 15 April 1803, while provisioning for the expedition he would soon be leading across the continent, Meriwether Lewis wrote to General William Irvine, the superintendent of military stores in Philadelphia, regarding the purchase of 200 pounds of portable soup, an item he regarded as “one of the most essential articles” on his list of needs.[2]Steve Harrison, “Meriwether Lewis’s First Written Reference to the Expedition—April 15, 1803,” We Proceeded On, October 1983, pp. 10-11. Lewis wound up paying $289.50 for 193 pounds of portable soup, all of it prepared by a Philadelphia cook named François Baillet and stored in 32 tin canisters purchased for eight dollars.[3]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, pp. 78, 79, 81, and 95. Contrary to … Continue reading

Anyone who has planned an extended wilderness back-packing trip involving a mixed group of hikers knows the difficulty of estimating the amount and types of food required. Simple mistakes in planning are difficult to correct once in the field and can lead to problems down a distant bend in the trail. Lewis was faced with a much more difficult planning exercise—one that called for a lot of guesswork in determining provisions for a party of still undetermined size bound on a journey of unknown length. He knew they would be living off the land to some considerable extent. Still, whatever game was shot in the field would have to be supplemented by preserved food carried on the trail.

A Recipe

Also known, among other names, as pocket soup and veal glue, portable soup is the ancestor of the modern bouillon cube and a close cousin to the grace de viande used in French cooking. Ingredients and proportions may vary slightly from one recipe to another, but all result in the same end product: a small, rubbery slab with an intense, meaty taste. Although we don’t know the exact formulation of Lewis’s portable soup, it was probably similar to the following recipe, which appears in a cookbook by Ann Shackleford published in London in the 1760s:

Take four calves feet; buttock of beef, twelve pounds; fillet of veal, three pounds; leg of mutton, ten pounds. Stew them in a sufficient quantity of water, over a gentle fire, and carefully take off the skum, pass the broth through a cullender, then boil the remaining meat in fresh water, which strain off likewise, and put the two liquors together, let them cool, in order to take off the fat; and clarify the broth with the whites of five or six eggs, adding resquisite quantity of salt; then pass the liquor through a flannel bag, and evaporate it in a tin vessel in boiling water, to the consistence of a very thick paste; turn it out of the vessel on a smooth even slab, and spread it thin: when cold, cut it in lozenges of a considerable size; which may be dried in the heat of boiling water, or in a stove, till they are perfectly hard, and somewhat brittle. Lastly, put them into wide-mouth glass bottles, and cork them well for use. These lozenges, or cakes, will keep good four or five years. You may, if you please, add to the composition, fowl, leguminous roots, or spices, as a few cloves, a little cinnamon, pepper, &c.[4]Ann Shackleford, The Modern Art of Cookery Improved (London: J. Newbery, ca. 1767), as quoted by Paul Jones on the Web site http://alt.xmission.com/~drudy/hist_text-arch/ 0373.html. The same … Continue reading

Later, the “glue” resulting from this recipe would be reconstituted as needed by adding boiling water, probably at a one-to-one ratio.

Nutritive Value

How nourishing was the portable soup carried on the expedition? Nutritional science provides an interesting answer. Some years ago, I asked Dr. Alison Eldridge, the associate director of the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota, to conduct a nutritional assay of a sample of portable soup based on the Shackleford recipe. The results are shown in the table on page 26.

At a one-to-one ratio, 125 grams of dehydrated portable soup mixed with 125 grams (a half cup) of boiling water yields one cup of broth. This is the amount one would expect for a single serving, or ration.[5]This assumes that in its dehydrated state the expedition’s portable soup was 61 percent water, as noted in the accompanying table. The recipe makes 8.3 kilograms (18.3 pounds) of dehydrated soup, which combined with an equal quantity of water would yield 66 rations.[6]The figure of 8.3 kilograms is rounded off from 8,294 grams. The exact yield is 66.35 rations (8,294 grams of protein, fat, and salt, plus 8,294 grams of water, divided by 250). Each ration would provide one person with 231 calories contained in 36 grams of protein and 8.5 grams of fat. With these proportions as a guide, one can estimate that the 193 pounds (87.6 kilograms) of portable soup carried on the expedition would have provided about 700 rations, or roughly 21 rations for each of the 33 members of the permanent party.[7]The precise number of rations is 696. In the calculations for rations per person I am including Sacagawea‘s infant, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, and excluding Toby and his son, the two Lemhi … Continue reading

The metabolic reduction of food in the body to yield energy is an oxidative process, analogous to the combustion of fuel but much more complex. The energy needs of a 25-year-old person engaged in strenuous physical labor of the sort endured by members of the Corps of Discovery can reach as high as 6,000 calories per day.

Those needs were surely at their maximum during the 11 days in late September 1805 when the explorers followed the Lolo Trail across the rugged Bitterroot Mountains.[8]The party left Travelers’ Rest, near present-day Missoula, Montana, on 11 September 1805. Clark led an advance group onto Weippe Prairie on 20 September 1805, and Lewis arrived there on 22 … Continue reading Until this time they had lived mostly off the land, which had been easy to do on the game-rich high plains of the upper Missouri. But once in the mountains they found game scarce, and they had cached the bulk of their remaining stores of corn, wheat, and salt pork below the Great Falls. Facing conditions of near-starvation in the Bitterroots, they killed some of their horses for meat and—almost certainly for the first time—turned to their supply of portable soup for sustenance.[9]In his journal entry for 29 June 1805, Sergeant John Ordway says that the party, after a drenching in a hard rain at the Great Falls of the Missouri, “revived with a dram of grog and got some … Continue reading

Assuming that no carbohydrates in the form of grains or vegetables were added to the re-hydrated soup when the explorers first began consuming it on the Lolo Trail, it would have taken 26 rations per person per day to give each of them the 6,000 calories their bodies required. This is five more rations per person than the number provided for the entire trip.[10]There is no evidence in the journals that carbohydrates—energy-packing nutrients that ought to make up 55-60 percent of a balanced diet—were added to the soup.

Nutrient Profile

Ingredients

- 4 pork hocks (substituted for 4 calves feet) 12 lbs. beef

- 3 lbs. veal

- 10 lbs. mutton

- 1/2 cup (250 grams) salt

The pork hocks were substituted for calves feet, which are not in the NCC’s database. The cuts of beef, veal, and mutton were fairly lean—they had no visible fat, although of course some fat would have been present. Shackleford’s recipe mentions that egg whites are used to clarify the broth, but because they coagulate and are then removed, they contribute no nutrients to the end product. The recipe doesn’t state the amount of salt added; relative to the total ingredients, a half cup is consistent with commercial beef-based condensed soups.

The recipe doesn’t say how much water to use in rendering the ingredients into the “thick paste” that is subsequently cut into lozenges and stored in sealed glass bottles. When cooking down the ingredients in the series of steps called for by the recipe, we used a “sufficient quantity” of water, as required. The dehydrated end product turned out to be 61 percent water—considerably drier than modern condensed soups, which are 72-92 percent water.

Yield

- Protein: 2,391 grams

- Fat: 563 grams

- Sodium: 61 grams

- Water: 5,090 grams

- Additional ingredients: 186 grams[11]Additional ingredients include a variety of other soluble salts besides sodium, as well as vitamins, amino acids, and cholesterol. 3 For a complete list, contact the author at 5551 Cottonwood Road, … Continue reading

- Total weight of all ingredients:

- 8,291 grams (8.3 kilograms, or about 18.3 pounds)

- Energy: 15,312 calories

- Calories from protein: 62 percent

- Calories from fat: 33 percent

- Other nutrients (selective list):

- Cholesterol: 7,351 milligrams

- Niacin: 520 milligrams

- Iron: 189 milligrams

- Vitamin B-6: 29 milligrams

- Riboflavin: 24 milligrams

- Thiamin: 10 milligrams

- Vitamin C: 1 milligram[12]Assay by the Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), University of Minnesota based on Ann Shackleford’s recipe for portable soup. Values are rounded off to eliminate decimal points.

Usage on the Trail

Among the supplies and provisions purchased for Captain Lewis in the spring of 1803 by Israel Whelan, the Purveyor of Public Supplies, was 193 pounds of portable soup made in Philadelphia by a cook named François Baillet,[13]Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2 vols, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:81. at a cost of $289.50. In the 1750s the British Navy had begun issuing 50 pounds of portable soup for every 100 sailors on long voyages, partly to vary the daily diet of salt-cured meats, and partly in the mistaken belief that it would prevent scurvy.[14]Meryl Rutz, “Salt Horse and Ship’s Biscuit: A Short Essay on the Diet of the Royal Navy Seaman During the American Revolution,” … Continue reading It was also widely used as a supplement and an emergency ration during the Revolutionary Era.

—Joseph Mussulman

The journals reveal that while in the Bitterroots the expedition members dined on portable soup for seven straight days—14 September 1805 to 20 September 1805.[15]Moulton, Vol. 9, pp. 223-226 (Ordway) and Vol. 11, pp. 315-324 (Whitehouse). The entries don’t tell us anything about the size of the rations, and there is no indication that the explorers had soup more than once a day. Almost certainly they consumed several cups at a time, for most of it was gone by the 20th, when Lewis tells us that only “a few” of the 32 canisters remained.[16]Moulton, Vol. 5, p. 211. Food historian Leandra Holland estimates that the explorers consumed 130 of the 193 pounds of portable soup they carried while in the Bitterroots. See her article … Continue reading

The portable soup helped keep metabolic fires burning, but it was no one’s favorite fare. Sergeant Patrick Gass noted in his journal entry for 14 September 1805, “Capt. Lewis gave out some portable soup, which he had along, to be used in cases of necessity.” Because “Some of the men did not relish this soup,” they killed a colt “and set about roasting it.[17]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), Vol. 9, p. 142. On the same day, his fellow sergeant John Ordway observed that they “had nothing to eat but Some portable Soup,” which “did not Satisfy.”[18]Ibid., p. 223. Although there is no direct evidence for it, one cannot rule out the possibility that the expedition’s portable soup was contaminated by bacteria. If so, it may have been unfit … Continue reading The journals state that they made soup by mixing the dehydrated glue in hot water, but the entries also suggest they sometimes took it straight, dissolved on the tongue: Private Joseph Whitehouse refers to drinking soup and also to eating it.[19]Moulton, Vol. 11, pp. 317 and 322 (drinking) and pp. 315-316, 320, and 323 (eating) There was certainly precedent for this. In a passage on portable soup in his History of the Dividing Line (1729), William Byrd of Virginia advised, “if you shou’d be faint with Fasting or Fatigued, let a small Piece of this Glue melt in your Mouth, and you will find yourself surprisingly refreshed.”[20]Quoted from Paul Jones’s Web site.

Whether taken as a drink or a lozenge, we can only guess how “refreshed” portable soup may have left Whitehouse and the others, but after at last emerging from the Bitterroots, none of the journal-keepers mentions partaking of it again. On the homeward journey the following spring, while waiting for the mountain snows to melt, the captains gave an ailing Nez Perce chief “a little portable soup”—not as food, however, but as medicine, in prescribed doses along with laudanum, flour of sulfur, and cream of tartar.[21]Moulton, Vol. 7, p. 284 (Lewis’s entry for 24 May 1806) and p. 289 (entry for 26 May 1806).

Portable soup: whatever its nutritional values or healing powers, for the Corps of Discovery it was the ration of last resort.

Notes

| ↑1 | Kenneth C. Walcheck, “Portable Soup: Ration of Last Resort,” We Proceeded On, August 2003, Volume 29, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol29no3.pdf#page=25. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Steve Harrison, “Meriwether Lewis’s First Written Reference to the Expedition—April 15, 1803,” We Proceeded On, October 1983, pp. 10-11. |

| ↑3 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, pp. 78, 79, 81, and 95. Contrary to speculation in some published accounts of the expedition, it is clear from the “Camp Equipage” list compiled by Lewis (Jackson, Vol. 1, p. 95) that the canisters were made of tin and not lead. See, for example, Eldon G. Chuinard, Only One Man Died: The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur Clark Co., 1980), p. 160, and Albert Furtwangler, Acts of Discovery: Visions of America in the Lewis and Clark Journals (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), p. 107. Also, according to food historian Leandra Holland, examination of a photocopy of Lewis’s camp-equipage list shows that the “of” in line “32 [Tin] Cannisters of P. Soup” has been overwritten with the word “for,” making it clear that the portable soup and the canisters were purchased separately. |

| ↑4 | Ann Shackleford, The Modern Art of Cookery Improved (London: J. Newbery, ca. 1767), as quoted by Paul Jones on the Web site http://alt.xmission.com/~drudy/hist_text-arch/ 0373.html. The same quotation, along with other recipes for portable soup, can be found on the Web site http://world.std.com/~ata/soup.htm. A similar recipe from 1753 also appears in Harrison, p. 11. |

| ↑5 | This assumes that in its dehydrated state the expedition’s portable soup was 61 percent water, as noted in the accompanying table. |

| ↑6 | The figure of 8.3 kilograms is rounded off from 8,294 grams. The exact yield is 66.35 rations (8,294 grams of protein, fat, and salt, plus 8,294 grams of water, divided by 250). |

| ↑7 | The precise number of rations is 696. In the calculations for rations per person I am including Sacagawea‘s infant, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, and excluding Toby and his son, the two Lemhi Shoshones who guided the explorers across the Bitterroots. |

| ↑8 | The party left Travelers’ Rest, near present-day Missoula, Montana, on 11 September 1805. Clark led an advance group onto Weippe Prairie on 20 September 1805, and Lewis arrived there on 22 September 1805. |

| ↑9 | In his journal entry for 29 June 1805, Sergeant John Ordway says that the party, after a drenching in a hard rain at the Great Falls of the Missouri, “revived with a dram of grog and got some warm Soup.” This might have been portable soup, but given the abundance of game at the Great Falls, it was almost certainly made from fresh meat. On 26 June 1805, when listing items carried in canoes, Ordway refers specifically to “portable Soup.” Moulton, Vol. 9, pp. 174 and 177. |

| ↑10 | There is no evidence in the journals that carbohydrates—energy-packing nutrients that ought to make up 55-60 percent of a balanced diet—were added to the soup. |

| ↑11 | Additional ingredients include a variety of other soluble salts besides sodium, as well as vitamins, amino acids, and cholesterol. 3 For a complete list, contact the author at 5551 Cottonwood Road, Bozeman, MT 59718. |

| ↑12 | Assay by the Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), University of Minnesota based on Ann Shackleford’s recipe for portable soup. Values are rounded off to eliminate decimal points. |

| ↑13 | Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2 vols, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:81. |

| ↑14 | Meryl Rutz, “Salt Horse and Ship’s Biscuit: A Short Essay on the Diet of the Royal Navy Seaman During the American Revolution,” http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1776salthorse.htm, accessed November 27, 2004. “Salt horse” was Navy slang for salt pork or beef. See also Leandra Zim Holland, Feasting and Fasting with Lewis & Clark: A Food and Social History of the Early 1800s (Emigrant, Montana: Old Yellowstone Publishing, 2003), 8-9. |

| ↑15 | Moulton, Vol. 9, pp. 223-226 (Ordway) and Vol. 11, pp. 315-324 (Whitehouse). |

| ↑16 | Moulton, Vol. 5, p. 211. Food historian Leandra Holland estimates that the explorers consumed 130 of the 193 pounds of portable soup they carried while in the Bitterroots. See her article “Empty Kettles in the Bitterroots, pp. 18-23 of this issue of WPO. |

| ↑17 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), Vol. 9, p. 142. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., p. 223. Although there is no direct evidence for it, one cannot rule out the possibility that the expedition’s portable soup was contaminated by bacteria. If so, it may have been unfit for consumption. All cooked meat products, including gravy and stock, are classified as high-risk foods which can support the growth of harmful pathogens. Bacteria could have entered the portable soup when it was being made in Philadelphia. |

| ↑19 | Moulton, Vol. 11, pp. 317 and 322 (drinking) and pp. 315-316, 320, and 323 (eating) |

| ↑20 | Quoted from Paul Jones’s Web site. |

| ↑21 | Moulton, Vol. 7, p. 284 (Lewis’s entry for 24 May 1806) and p. 289 (entry for 26 May 1806). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.