Eastern Beginnings

10 January–30 August 1803

The Lewis and Clark Expedition ostensibly began in February 1801 when President Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Army commander General James Wilkinson requesting that Lieutenant Meriwether Lewis become the President’s personal secretary. Exploration of North America’s western half had long been a goal of the president, and now he had a young protégé who might lead such an expedition.

On 18 January 1803, Lewis hand-delivers to the U.S. Congress the President’s request to fund what would become known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The President works in Washington City and Monticello to craft instructions and line up the best talent to assist Lewis. In France, three diplomats negotiate with Napoleon Bonaparte to purchase the Louisiana Territory.

Meriwether receives training, supplies and equipment in Philadelphia and avails himself of armaments and specialized equipment—including a collapsable iron-framed boat—at the Schuylkill and Harpers Ferry arsenals. By July 1803, everything is at Fort Fayette in Pittsburgh. All Lewis needs is a large boat to carry everything down the Ohio. He also needs to know if William Clark will accept his invitation to join him.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Down the Ohio

31 August–13 November 1803

On 31 August 1803, after months of preparation, Lewis and his crew finally head down the Ohio River. Unfortunately, the water is so low that they must frequently unload and tow the overloaded barge with horses and oxen.

At the request of President Jefferson, Lewis disembarks at Cincinnati and travels overland to gather fossils at Big Bone Lick. He meets the boats, and together they continue to the Falls of the Ohio to pick up William Clark and several new recruits.

The expedition arrives at Fort Massac near the mouth of the Ohio on 11 November. There, they meet George Drouillard and immediately hire him as an interpreter. His first mission is to find the missing army recruits from Fort Southwest Point in Tennessee.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Up the Mississippi

14 November—11 December 1803

On 20 November 1803—after the expedition encamps nearly a week at the mouth of the Ohio—the barge and boats are moved against the Mississippi current.

The crews work their way to Fort Kaskaskia—recently constructed in the Illinois Territory to support the transfer of the Louisiana Territory—ceded to France on 30 November yet still controlled by Spain. At Kaskaskia, the captains recruit twelve soldiers. They are also told that Spain will not allow them to continue up the Missouri until at least the next spring.

In early December, Lewis negotiates winter arrangements with the Spanish governor in St. Louis. Then, on 11 December, Clark arrives with the boats displaying full sails and colors. The American soldiers could visit the city, but the expedition would not be able to build winter quarters there.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Winter at Wood River

12 December 1803–13 May 1804

In mid-December 1803, construction of winter quarters begins. In accordance with the wishes of the Spanish Governor, Lewis could work in St. Louis and the soldiers could build a garrison in Illinois across from the mouth of the Missouri. The Wood river cantonment is known today as Camp River Dubois.

In St. Louis, Lewis learns about the Missouri River from established St. Louis traders and purchases more Indian gifts and equipment from local merchants. Across the river, the captains would need ot establish military discipline and the soldiers would need to become a team.

Both captains and key personnel cross the Mississippi frequently, and in March, Lewis and Clark witness the official transfer of Upper Louisiana from Spain to France. One day later, France transfers the territory to the United States.

With the arrival of several St. Charles French boatmen from St. Charles on 11 May 1804, departure up the Missouri is imminent.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Up the Missouri

14 May–20 July 1804

On 14 May 1804—after more than a year of preparation and travel—the boats leave Camp River Dubois and head up the Missouri River. At St. Charles, the two captains, Clark’s slave York, interpreter George Drouillard, eight or nine French engagés, 34 enlisted men, and Lewis’s dog Seaman depart in three boats: the barge and two large pirogues.

Everyone quickly learns of the struggles and hazards of moving up the Missouri with its many sawyers and sandbars. Despite the overloaded boats and several close calls, they safely pass many landmarks made familiar by earlier traders from St. Louis.

Crossing the present state of Missouri and then heading north along the Kansas-Missouri border, they pass the homelands of the Omaha, Kansa, Otoe, and Pawnee. On 21 July, they reach the mouth of the Platte where only a handful of traders had ever continued north towards the Knife River Villages.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Past the Omahas

21 July–20 August 1804

Following the Missouri River north along the present Nebraska-Iowa border, the expedition passes the homelands of the Otoes and Omahas. The captains pay their respects to the late Omaha Chief Blackbird and conduct their first two councils, one with the Otoes and another with the Omaha.

Strong currents, heat, sandbars, sawyers, and masses of driftwood make hard days for the enlisted men and engagés, and Pvt. Moses Reed and an engagé desert.

Shortly after the council with the Omahas, Sgt. Charles Floyd becomes ill, and passes away. He is buried “with all the honors of War” on a bluff overlooking the river in present Sioux City, Iowa.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Among the Yanktons

21 August–8 September 1804

Moving along the present border between Nebraska and South Dakota, the expedition turns its ‘enlightened‘ attention to several features in the upper Missouri River mythology.

Instead of a volcano, they find blue earth, cliffs of white marl, and burning bluffs. Lewis becomes ill while testing one of the minerals he found. Instead of La Véndrye’s Golden Sands, they find hills of wind-blown loess. Instead of a Spirit Moundmountain of little people and devilish spirits, they find birds feeding on pissants atop present Spirit Mound.

Pvt. George Shannon fails to return from a hunting trip, and Patrick Gass is promoted to sergeant. At Calumet Bluff, their attention turns to receiving the Yankton Sioux. For two days, a council with speeches, gifts, songs, and dances is held.

At Old Baldy—present The Tower in South Dakota—everybody but the camp guard visits a prairie dog town, and they manage to capture one as a live specimen. He would travel to the Knife River Villages, Washington City, and reside in Peale’s Museum in Philadelphia.

Their encounters here had been encouraging, but Shannon is still missing, and the Lakota Sioux homelands are just ahead.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Crossing the Lakotas

9 September–25 Oct 1804

Moving the flotilla of boats up the Missouri in the present states of South and North Dakota, the expedition encounters several nations with limited experience with St. Louis-based traders.

Soon after going around the Big Bend of the Missouri, they meet the Lakota Sioux, and a multi-day encounter goes badly for both peoples. They proceed on to some Arikara villages where they hold a council and invite Too Né (Eagle Feather) to travel with them. He provides useful information and would eventually visit Washington City.

In late October, they reach the Knife River Villages—a complex of Hidatsa and Mandan villages. With winter quickly approaching, they must act fast to establish winter quarters.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Winter at Fort Mandan

26 October 1804–6 April 1805

On 2 November 1804 below the Knife River Villages, work begins on the expedition’s winter fortification. The men’s quarters, storage rooms, and the 16-foot pickets, are designed for defense against hostile Indians, especially the Sioux, who would be quite troublesome, although they never attacked the fort directly. “This place we have named Fort Mandan,” Lewis recorded, “in honour of our Neighbours”—their kind and congenial Mandan Indians. Here they celebrate their second Christmas and New Year’s Day.

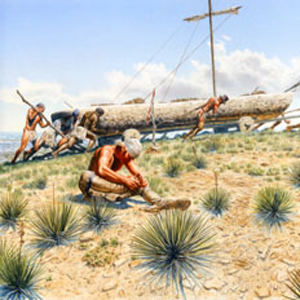

On 28 February 1805, sixteen enlisted men are assigned to hew six canoes from cottonwood logs, and they finish them in 22 days. Meanwhile, the rest of the men make rope, leather clothing and moccasins, cured meat, and battle axes to trade for corn. Lewis prepares botanical, zoological, and mineralogical specimens for shipping back to President Jefferson. Clark works on his Fort Mandan maps.

By the time they are ready to leave Fort Mandan, they add some key members to the permanent party: Toussaint Charbonneau, his wife and infant son—Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste, and French trader Jean-Baptiste Lepage. Each would play critical roles in the expedition’s journey to the Pacific Ocean.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Along the Northern Reach

7 April–12 June 1805

At 4 p.m. on 7 April 1805, the permanent party heads their six canoes and two pirogues up the Missouri toward the Rocky Mountain barrier. At the same moment, Corp. Warfington and a small crew accompanied by Too Né’s delegation bound for a meeting with President Jefferson head downriver in the barge.

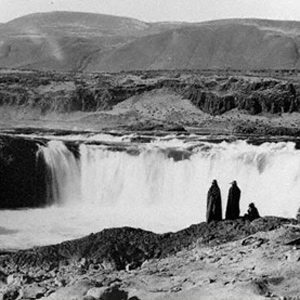

The Missouri River reaches it most northern position flowing from the Great Falls of the Missouri across present Montana and North Dakota. Moving through this stretch, the expedition passes the Yellowstone, Milk, Poplar, and Musselshell rivers. In the Upper Missouri River Breaks, the journalists describe both “scenes of barrenness and desolation” and “seens of visionary inchantment”.

At the mouth of the Marias, they come to a river they did not expect. They are unsure which fork is the true Missouri. After ten days exploring each, the captains decide to take the left fork.

Lewis scouts ahead to find the Falls of the Missouri that they are expecting. Sacagawea becomes dangerously ill and travels with Clark and the boats until they can go no farther—below present Belt Creek.

If the expedition is to be successful, Sacagawea will need gain her health, and the heavy boats will need to be carted around not one, but several waterfalls on a long and difficult portage.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Portaging the Falls

13 June–12 July 1805

On 12 June 1805, Lewis leaves Decision Point at the mouth of the Marias to find the Great Falls of the Missouri. He finds them “truly magnifficent and sublimely grand”.

After traveling separate routes from Decision Point, Clark and Lewis reunite at what would become known as Lower Portage Camp. Clark leaves to survey a portage route, and Lewis attends to Sacagawea whose condition has become “Somewhat dangerous”.

Wheels and trucks are built from cottonwood trees, and the dugouts are hauled two miles up Belt Creek. Lewis leads the first canoe overland to the White Bear Islands where he focuses on construction of the iron-framed boat.

Several trips are needed—as are several truck repairs—to get all the canoes and baggage to the upper portage camp. While site seeing during the last stage, Clark, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste are nearly swept away in a flash flood.

Celebrating the Fourth of July, they drink the last of whiskey. Then, due to a lack of pitch pine in the area, the cover of the iron-framed boat leaks too much water to be of practical use and is cached.

Clark moves a few miles up the river and his crew builds two more canoes so that they can continue up the Missouri.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Gates of the Rockies

13 July–17 August 1805

Above the Great Falls of the Missouri, the expedition continues up the Missouri River in eight dugout canoes. There, the river flows along and through the eastern arms of the Rocky Mountains. Clark lists each river constriction as a gate, gap, or narrow.

| Clark’s description | Date | Present-day name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Rockey Mountains at Pine Island rapid | 16 July 1805 | Tower Rock |

| 2. | Great Gate of the Rock Mouts. | 19 July 1805 | Gates of the Mountains |

| 3. | Little Gate of the Mountain | 25 July 1805 | Toston Dam, Lombard |

| – | three forks of Missouri | 27 July 1805 | Three Forks, Headwaters of the Missouri |

| 4. | Narrows of the 3d Mountain | 1 August 1805 | Jefferson Canyon |

| 5. | 4th Gap of the Mountain | 15 August 1805 | Rattlesnake Cliffs |

| 6. | Rapid at the narrows of 5th Mtn. | 16 August 1805 | Beaverhead Canyon Gateway |

1 From Clark’s list of “Estimated Distances”.

Below Three Forks, Montana, the Missouri River ends—fed by three forks named by the captains: the Gallatin, Madison, and Jefferson. They continue up the Jefferson until it too forks into three rivers.

The Beaverhead River is only a sixth the size of the Missouri, and the enlisted men must walk the heavy dugouts up the shallow rapids. They are encouraged when Sacagawea sees familiar landmarks such as Beaverhead Rock.

To get to the waters of the Columbia, they would need horses. The captains take turns scouting ahead by land to find the Shoshones who they hope will have horses. While crossing the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass, Lewis finally meets them.

Clark would continue with most of the party moving the boats up the shallow Beaverhead. By the time they reach the end of the navigable river, Lewis and a group of Shoshones are waiting for them. One journalist would later name the place Fortunate Camp.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Down the Western Valleys

11 August–10 September 1805

Having reached the end of the navigable Missouri, the captains—aided by Lemhi Shoshone Chief Cameahwait, Sacagawea‘s brother—begin acquiring horses, making pack saddles, and caching supplies they can no longer take with them.

With the help of the Lemhi Shoshones, everything is carried across the Continental Divide. Clark and their new guide they call Toby, scout the Salmon River and find it is not navigable.

After nearly three weeks with the Shoshones, the expedition moves down the Lemhi River valley and heads up the North Fork Salmon River. The captains ignore Toby’s advice to follow the Indian Road, and they are forced to spend a snowy night near the summit of Lost Trail Pass.

Dropping down from Lost Trail Pass, the Flathead Salish give them a warm welcome and sell them some horses. The expedition then proceeds down the Bitterroot River Valley to Travelers’ Rest where they have yet to cross the Bitterroot Mountains.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Over the Bitterroots

11 September–22 September 1805

On 11 September 1805, the expedition leaves Travelers’ Rest and follows a trail high above Lolo Creek in Montana. After passing some hot springs, they follow a trail to the Bitterroot divide at Packer Meadows.

They briefly follow the Lochsa River, but due to its steep canyons, they must climb to the ridges high above. It then commences snowing and there is virtually no game to be had. At one point, Clark writes “I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life”.

The travelers subsist on portable soup, tallow melted from candles, and their own precious horses. Clark and a small party scout ahead eventually reaching two Nez Perce villages at Weippe Prairie. They are welcomed and given food, much of which is sent back to Lewis with the main party.

The expedition moves down to the Clearwater River where a camp is established to build canoes. Unfortunately, most of the men are too sick to help.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Among the Nez Perce

20 September–17 October 1805

Fatigued and physically sick after crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, the expedition is aided by the Nez Perce. With their help, they find a location on the Clearwater River to build five dugout canoes and employ the Nez Perce method of burning out the Ponderosa pine logs.

The Nez Perce agree to take care of the expedition’s horses while they continue to the Pacific Ocean. Two Nez Perce chiefs volunteer to guide them down the Clearwater and Snake to the Columbia. The guides help scout the rapids and introduce the expedition to the various Nez Perce and Palouse bands fishing in the many rapids.

On 16 October 1805, they negotiate the last Snake River rapid and arrive at the Columbia River where many Yakamas and Wanapums are gathered. About two hundred men approach, singing and beating their drums.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Down the Columbia

18 October–6 December 1805

In five battered dugout canoes, the expedition paddles down the Columbia River—a river that they know will take them to the Pacific Ocean. They safely pass a series of rapids and falls between Celilo Falls and the Cascades of the Columbia. In the Columbia River Gorge, they see stunning geologic features.

The river calms, and they enter one of the most populated areas of their entire journey with numerous villages of Upper and Lower Chinook. Nearing the ocean, they find the Columbia River estuary is miles long and miles wide. They must hunker down in small nitches on the northern shore several days before they can reach the end of their water journey at Baker Bay.

At Station Camp, the captains survey the party as to where they would like to spend the winter. Everyone’s opinion—including York and Sacagawea—are written down. They decide to cross the river where according to the Clatsops, there are many elk. They set up a camp on a narrow spit of land on the opposite side—present Tongue Point at Astoria, Oregon. Lewis takes a small party to find a suitable location to build a fort, but when he fails to return after five days, Clark begins to worry.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Winter at Fort Clatsop

7 December 1805–22 March 1806

The expedition leaves Tongue Point on 7 December 1805, and immediately upon their arrival at a small point of land above the Netul River, begin to construct winter quarters. They would name it Fort Clatsop in honor of their neighbors.

The weather is sometimes snowy, sometimes icy, but almost always rainy. Their diet is typically elk, which quickly spoils in the warm, wet climate. Visiting Clatsops and Kathlamets sell them sturgeon, wapato, and eulachon as well as woven mats, bags, and waterproof conical hats.

A saltworks near present Seaside, Oregon is established to make salt by boiling seawater. In early January, Clark visits the salt works on his way to get blubber from a beached whale. Sacagawea, who hadn’t yet seen the ocean, insists she be included in his group.

After the dark and damp coastal winter and nearly two years since leaving St. Louis, everyone is anxious to head back.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Return to the Clearwater

23 March–9 June 1806

The desire to return to St. Louis motivates the paddlers as they head up the Columbia River. Across from the Sandy River, they stop to hunt and dry meat. They explore the Willamette and Sandy hoping that one of them is the fabled river that comes from California.

Below Celilo Falls, they begin trading for horses and by the time they reach the Walla Walla River, they have enough horses to take the overland Travois Trail back to the Snake River. They then continue by horse up the Clearwater River.

At Kamiah in present Idaho, they establish a “Long Camp” among the Nez Perce to wait for mountain snows to melt. Sgt. Ordway takes a side trip to the Salmon and Snake rivers where some Nez Perce fishers are catching salmon.

After five weeks sharing with the Nez Perce, they head to the mountain trails that will take them to the land of the buffalo.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Roads to the Buffalo

10 June–14 July 1806

With the acquisition of horses, Native Nations crossing the Rocky Mountains to hunt for bison became more common. Two of their trails are used by the captains—in separate groups—to return to the bison-rich plains.

After crossing the Bitterroot Mountains on what is known today as the Lolo Trail, the expedition divides forces at Travelers’ Rest. Lewis takes one group east and north up the Blackfoot River and then over Lewis and Clark Pass. They return to their old camp above the Great Falls of the Missouri to retrieve supplies and specimens cached there.

From Travelers’ Rest, Clark goes up the Bitterroot River and crosses the Continental Divide at present Gibbons Pass. They cross the Big Hole Valley and return to Fortunate Camp where they had cached tobacco, food, and most of the canoes.

At the Headwaters of the Missouri, Sgt. Ordway’s detachment paddles the canoes down the Missouri destined for the portage of the Great Falls. Clark’s group–along with all the horses—travel up the Gallatin River valley on their way to the Yellowstone River.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Clark on the Yellowstone

15 July–11 August 1806

Having traveled up the Gallatin River and over Bozeman Pass, Clark, York, the Charbonneau family, and eight enlisted men arrive at the Yellowstone River near present Livingston, Montana.

They travel by horse for several days before finding cottonwood trees large enough to make canoes. By the time they finish two small dugouts, most of their horses are stolen—likely by Crows.

Sgt. Pryor and three privates take the remaining horses across the river and follow an Indian road leading to the Knife River Villages. They would not get far before all their horses are stolen. The small detachment returns to the river where they construct two bull boats from willow and bison hides. Now far behind Clark, they would need to paddle hard if they are to ever rejoin the expedition.

In the two new dugouts, Clark’s party of nine encounter large herds of bison as they paddle down the river. They reach the Missouri River on 3 August with relative safety. Chased by swarms of mosquitoes, they move slowly down the Missouri for several days, but they can find no sign of Lewis and his group.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Lewis on the Marias

16 July–11 August 1806

Lewis can’t leave finding the source of the Marias River alone. If it comes from the far north, then that region will be considered part of the Louisiana Territory. With only three men, Lewis risks traveling through Blackfeet homelands to find the river’s source.

On 16 July, Lewis directs Sgt. Gass to portage the dugouts around the falls. Those boats are coming down the Missouri—paddled by a detachment lead by Sgt. Ordway. Lewis and his small group then leave the Great Falls of the Missouri bound for the Marias.

On Cutbank Creek, a small tributary, Lewis determines the headwaters will not extend America’s reach into present Canada. Attempts to take celestial observations are obscured by clouds, and the entire junket becomes a big disappointment.

Now in the heart of Blackfeet country, Lewis meets a group of young men, and when the latter attempt to steal rifles, a fatal encounter ensues. Both groups flee.

Riding all day and through the night, Lewis can only hope that he will find the relative safety of Gass and Ordway’s detachments and that together, they can paddle down the Missouri to reunite with William Clark at the mouth of the Yellowstone.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

The Final Leg

11 August–26 September 1806

While hunting on the Missouri River below present Williston, North Dakota, Lewis is accidentally shot through the flesh of his buttocks. The next day, they catch up to Clark’s party at Reunion Bay. As one united force, they are ready to sprint down the river to St. Louis.

At the Knife River Villages, they drop off the Charbonneau family and pick up Chief Sheheke and interpreter René Jusseaume who will visit Washington City.

The faithful paddlers meet several traders and receive flour, whiskey, woven shirts, and most importantly, news of the United States.

On 23 September 1806, the citizens of St. Louis—having given them up for dead—provide a boisterous welcome. The captains commence writing.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.