In 1809, the Charbonneaus traveled to St Louis. Jean Baptiste was baptized, Toussaint would try farming, and Sacagawea would become sickly.[1]This is an extract from Bob Moore, “Pompey’s Baptism,” We Proceeded On, February 2000, Volume 26, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The … Continue reading

Jean Baptist’s Baptism

On December 28, 1809, a small group of people gathered in the old vertical log church at St. Louis, near the site of today’s Old Cathedral beneath the Gateway Arch. Prayers were said and the sign of the eras was made with holy water on the forehead of a four-and-a-half-year-old boy. Words were spoken in French. “I baptize thee in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost,” intoned Father Urbain Guillet, a Trappist monk who stood before the group dressed in his plain white robe. Close by the young boy stood his father, Toussaint Charbonneau, and his mother, Sacagawea. Fifty-nine-year-old Auguste Chouteau, the co-founder of St. Louis, was present as godfather to the child, along with his twelve-year-old daughter, Eulalie. Conspicuously missing were Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Governor Lewis had died tragically along the Natchez Trace on 11 October 1809, just over two months earlier. General Clark had left St. Louis in September to travel to Washington, D.C., and was still there on 28 December, the date of the baptism.[2]See Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), pp. 468-469. After Charbonneau, Father Guillet, and the two Chouteaus signed the record book, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau the little boy whom William Clark called Pomp or Pompey, the toddler who shared the perils and adventures of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was a member of the Roman Catholic faith.

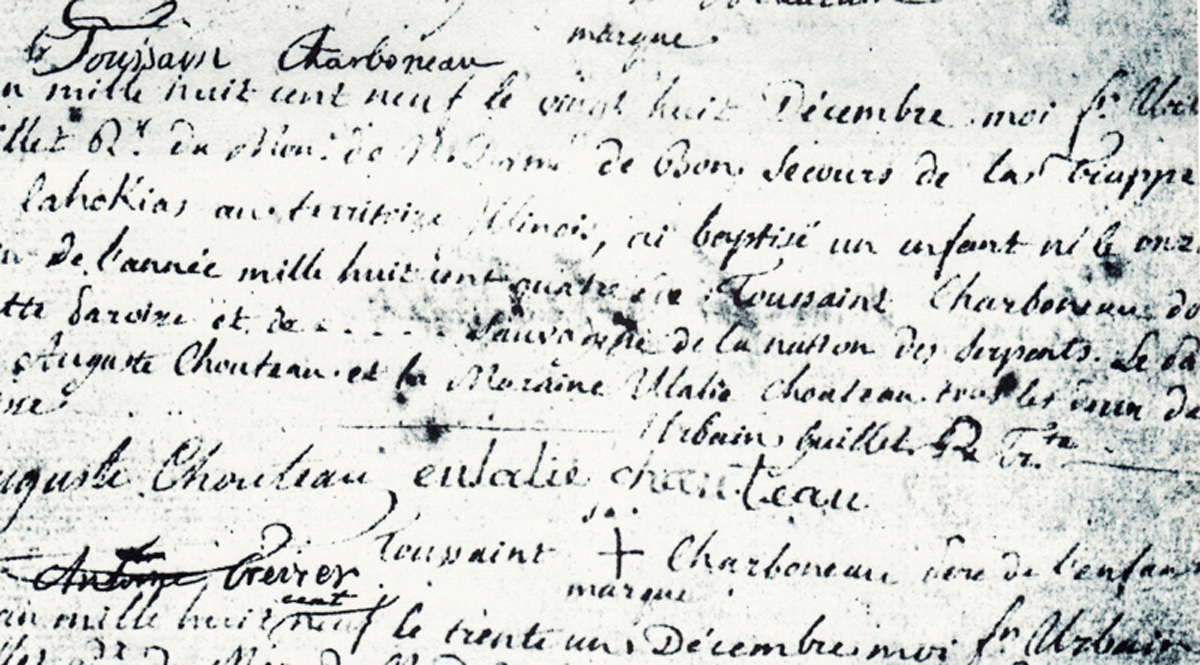

In researching the early records of St. Louis‘s Old Cathedral parish last winter, the author stumbled upon the baptismal record that is my basis for the preceding paragraph. The record, in French, is interesting for what it says and for what it does not say. It appears below in the original French and below that, a translation by Frank Mares of the National Park Service.[3]The record is included in the Register of Baptisms of the Old Cathedral Parish. My research was conducted with the kind permission of Monsignor Bernard Sandheinrich, pastor of the Old Cathedral.

Baptismal Record Transcript

[French]

Toussain Charboneau

L’an mille huit cent neuf le vingt huit Dccembre, moi, Fr. Urbain Guillet R + du mon de N. Dame de Bon Secours de la Trappe pris Cahokia, au Territoire Illinois, au baptise un enfant né le onze fevrier de l’année mille huit cent quatre de Toussaint Charboneau domicilié de cette patoisse et de __________ Sauvagesse de la nation des Serpents. Le parain a été Auguste Chouteau et la maraine Ulalie Chouteau tous les deux de cette paroisse.

Urbain Guillet R + Tr.te

Auguste Chouteau [signature]

Eulalie Chouteau [signature]

Toussaint X [sa marque] Charbonneau père de l’enfant

[English]

Toussain Charboneau

The year eighteen hundred nine the twenty-eighth of December, I, brother Urbain Guillet Reu of the Trappist monastery of Our Lady of Good Help near Cahokia, in the Illinois Territory, baptized a child born the eleventh of February in the year eighteen hundred four of Toussaint Charboneau, living in this parish and of __________ savage of the Snake Nation. The godfather was Auguste Chouteau and the godmother Ulalie Chouteau both of this parish.

Urbain Guillet R + Tr.te

Auguste Chouteau [signature]

Eulalie Chouteau [signature]

Toussaint X [his mark] Charbonneau father of the child

Why the Delay?

The birth of Sacagawea’s baby at the expedition’s Fort Mandan was chronicled by Meriwether Lewis in his journal on 11 February 1805. Subsequently, as Toussaint Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and the child shared in the trials and adventures of the expedition, traveling to the Pacific Coast and back in 1805–06, Clark took a particular interest in the boy. Upon the party’s return to the Knife River Villages, located near modern Stanton, North Dakota, the Charbonneaus chose not to continue to St. Louis. As Clark recorded in his journal on 17 August 1806: “we offered to convey him [Toussaint Charbonneau] down to the Illinois if he chose to go, he declined, proceeding on at present, observing that he had no acquaintance or prospects of making a liveing below, and must continue to live in the way that he had done. I offered to take his little son a butiful promising child who is 19 month old to which they both himself & wife wer willing provided the child had been weened. They observed chat in one year the boy would be sufficiently old to leave his mother & he would then take him to me if I would be so friendly as to raise the child for him in such a manner as I thought proper, to which I agreed &c.”[4]17 August 1806, Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), Vol. 8, June 9-September 26, 1806.

In reading this account, one might wonder why the Charbonneaus did not bring Pomp downriver in 1807, as Clark indicated they might do. It is well known that the Charbonneau family did not arrive in St. Louis until 1809 or 1810 to bring the boy to Clark to receive his promised education. The Charbonneaus were probably prevented from traveling to St. Louis by the hostilities of the Arikara nation, whose principal villages were located below the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, near modern Wakpala, South Dakota. This hypothesis make even more sense in the light of che discovery of Pomp’s baptismal record, which seems to pinpoint the arrival of the Charbonneau family in St. Louis in the autumn of 1809.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Charbonneau wanted his son to be baptized. St. Louis at that time was predominantly irreligious, and because we know the town had no resident priest in 1809, it took some effort to have the baptism performed. The man who did so, Father Urbain Guillet, was a Trappist monk who had to travel co St. Louis from an area near present-day Collinsville, Illinois, a winter journey of nearly twenty miles involving a crossing of the frozen Mississippi River. The Old Cathedral parish records show that Father Guillet was in St. Louis only between 24 and 31 December 1809, probably to celebrate Christmas Mass and perform any baptisms or weddings needed by parishioners. Therefore, the Charbonneaus had to make an extra effort to arrange Pomp’s baptism on 28 December, which was probably the soonest date after their arrival in St. Louis that the sacrament could have been administered. This means that the Charbonneaus must have arrived in St. Louis sometime between the visit of the priest from the Ste. Genevieve parish in the late summer of 1809 and the last week in December, when Father Guillet was in town.

Arikara Complications

There also may be a tie between the appearance of the Charbonneau in St. Louis and Pierre Chouteau‘s expedition of 1809 up the Missouri River to return Sheheke, a Mandan chief who had journeyed to St. Louis with the Corps of Discovery on its homeward journey in 1806.

Pierre, a half-brother of Auguste Chouteau, returned to St. Louis on 16 November 1809, just one month before the baptism.[5]See the letter of Pierre Chouteau to Secretary of War William Eustis, December 14, 1809, in The Territorial Papers of the United States, edited by Clarence Edwin Caner (Washington, D.C.: U.S. … Continue reading For the previous two years, passage on the Missouri River had been blocked by the Arikara, who were angry about the death of their chief, Ankedoucharo, during his 1805–6 visit to Washington, D.C. As a result, parties from St. Louis had been unable to travel upriver and parties at the Mandan villages—including the Charbonneaus—had been prevented from descending in safety.

The problems had started in September 1807, when Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor, a former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, had been promoted to ensign and given responsibility for delivering Sheheke to his people. Pryor’s party was attacked by the Arikara and forced to turn back.[6]Three men were killed and eight wounded, including George Shannon, who had to have his leg amputated as a result of his wounds. See Nathaniel Pryor to William Clark, 16 October 1807, in Donald … Continue reading In his capacity as governor of Louisiana, Meriwether Lewis in the spring of 1809 sent Pierre Chouteau on a second mission to deliver Sheheke. This involved chartering a private fur company, which was paid in part with government funds totaling $7,000. Lewis’s action prompted Secretary of War William Eustis to warn him that the government would no longer honor his letters of credit. This led in part to Lewis’s trip to Washington D.C., to clear his name—the trip on which be died at Grinder’s Stand.

In a letter to Pierre Chouteau dated 8 June 1809, Lewis stated that Chouteau’s primary mission was to return Sheheke whether he had to fight his way through the Arikaras or use diplomacy to restore peaceful relations with them.[7]See Gov. Meriwether Lewis to Pierre Chouteau, 8 June 1809, and Pierre Chouteau to the Secretary of War, 14 December 1809, in The Territorial Papers of the United States, edited by Clarence Edwin … Continue reading Choosing diplomacy, Chouteau was successful in his mission, arriving at the Mandan village on 24 September. The people of the Knife River villages, as well as the traders from St. Louis, must have been overjoyed that the river was open once again. As the expedition prepared to return downriver, it seems likely that the Charbonneaus would have sensed that the time was right to go to St. Louis. If they took passage on the return trip with Chouteau’s large, well-armed corps of soldiers and trappers (he had at least 125 men), their safety would be better assured than if they attempted to make the trip alone or with a smaller party.[8]Foley and Rice, pp. 143-148.

Trappists on the Mississippi

In addition to added information and conjecture on the Charbonneau family, Pomp’s baptismal record also sheds light on a little-known facet of St. Louis history: How and why did a Trappist monk come to be in St. Louis in 1809, and why was there no resident priest in the village? When the Spanish officially relinquished political control of St. Louis to the United States on 10 March 1804, the former governor, his staff, a small company of soldiers, and the village priest were out of work. Under the Spanish regime, parishioners had not been asked for contributions for the upkeep of the church or to pay the living expenses of the priest, for these costs were provided by the government. With no money for upkeep and the fate of the province uncertain, particularly in matters of religion, the resident priest departed with the Spanish authorities and the St. Louis church grew silent. Priests from surrounding parishes came to St. Louis sporadically to say an occasional mass, hear confessions, or perform baptisms, funerals, and marriages but there was no resident priest in the village until the arrival of Bishop Louis William Valentin DuBourg in 1818.[9]The one exception to this fact was the presence of an itinerant priest named Thomas Flynn from mid-1807 to January 1808. Flynn signed a contract with the St. Louis parishioners for a sum of money and … Continue reading

In July 1808 Father Urbain Guillet arrived in the St. Louis area with his Trappist brothers.[10]The monastery of La Trappe was founded in 1122, and made a branch of the Cistercian order in 1148. Trappist monks take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. They wear white robes instead of the … Continue reading They had left the Abbey of Val Sainte near Fribourg, Switzerland, in 1802 intending to set up a monastery for their order in America. They tried two locations before moving to the Mississippi River Valley, first at Pigeon Hills, Pennsylvania, and later at Pottinger’s Creek, Kentucky. Upon arrival in the St. Louis area, they first set up their quarters at Florissant, west of St. Louis. After a few months they moved east across the Mississippi River to an area near modern Collinsville, Illinois, where they built a temporary log monastery complex on top of an ancient Indian mound, today called Monk’s Mound because of their presence.[11]Monk’s Mound is today part of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, near Collinsville. It stands 100 feet tall and covers four acres of ground, the largest man-made structure built north of … Continue reading The land was claimed by Nicholas Jarrot of the village of Cahokia and given to the Trappists by him for their monastery.11 Many accounts state that the monks moved to Illinois in 1810, not 1809, yet Guillet’s eleven baptismal records of December 1809 at the Old Cathedral of St. Louis all clearly state that his monastery was “near Cahokia, in the Illinois Territory.”

Father Guillet was described by Bishop Martin Spalding as “a man of great piety, indefatigable zeal and activity, and of a singular meekness and suavity of manners.”[12]M.J. Spalding, Sketches of Early Catholic Missioners of Kentucky (Louisville, 1944 ). Others were critical of Guillet, who maintained the rigid rules of his order despite the new and severe surroundings of the American wilderness.[13]See Rev. John Rothensteiner; History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis (St. Louis, 1928), Vol. 1, pp. 21 9-220. Critics included Father Nerinckx, who traveled with Guillet in the wilderness and concluded that Guillet was “not a man in the right place.”[14]Quoted in Rev. John Rothensteiner, History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Vol. 1, p. 219. Whatever his qualifications or drawbacks, Father Guillet was on the scene to baptize Jean Baptiste Charbonneau on 28 December 1809.

The St. Louis Church

Church of the Holy Family, Cahokia, Illinois

© by Wiki Commons user Kbh3rd. Permission via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Indicative of the architectural style of the building in which the baptism occurred, the above church employs the common French posts on sill, or Poteau sur sole, construction. That is, vertical logs are placed on a horizontal timber foundation.

The church building in which young Pomp was baptized by Father Guillet bore little resemblance to today’s majestic Old Cathedral. The first church to be built in St. Louis was a log structure, little more than a shack, erected in 1770 by Don Pedro Piernas, the Spanish lieutenant governor, on the northeast corner of the cathedral lot. In 1772, St. Louis ordered a bell for its church, which is today displayed in the Old Cathedral Museum. In 1776, the growing town received its first pastor, Bernard de Limpach, a Capuchin monk, and a second church was built. This was a larger, vertical-log structure which measured 60×30 feet. It faced Second Street, midway between Walnut and Market. It had a small bell steeple and was surrounded by a porch, or “gallerie.” It was this second, vertical-log church in which Pomp was baptized.[15]See Gregory M. Franzwa, The Old Cathedral (Gerald, Mo., The Patrice Press, 1980), for more on the history of the four buildings which have stood on the site of the Old Cathedral. The present Old … Continue reading

Errors in the Record

To return to the baptismal record, sharp-eyed readers have probably noticed some discrepancies, all of which I think can be explained by the fact that Father Guillet, as a foreigner and a nonresident member of an ascetic sect of monks, did not know any of the people involved and probably misinterpreted or did not understand some of what he was told. Auguste Chouteau was probably not looked upon as a particularly important man by Guillet, nor did the Charbonneaus and their links with the Lewis and Clark Expedition mean anything to him. Thus, the date of Pomp’s birth was recorded incorrectly as 11 February 1804, instead of the correct 11 February 1805. Chouteau’s daughter’s name, Eulalie, was misspelled by Guillet. And Sacagawea’s name, which may have been past the point of translation for the monk, was left as a blank line. She was instead described as a “Sauvagesse de la nation des Serpents,” a reference to the Snakes, or Shoshonis [Shoshones]. The Charbonneaus are described, correctly, as “living in” or residing in the parish, while the Chouteaus are labeled as being “of this parish.”

Auguste Chouteau was easily the most important and revered private citizen in St. Louis in 1809. lt is a testament to the importance of Charbonneau and Sacagawea that Chouteau and his daughter were asked to stand as godparents to the child, and that they accepted. Eulalie, whose signature in the record book looks like that of the twelve-year-old girl she was, was the fifth of Auguste and Therese Chouteau’s nine children. Her full name was Marie Therese Eulalie Chouteau, and she was born on 3 May 1797. She married Rene Paul, a thirty-year-old veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, in April 1812 (shortly before her fifteenth birthday), and they had ten children before her death in 1835.[16]See Mary B. Cunningham and Jeanne C. Blythe, The Founding Family of St. Louis (St. Louis: Piraeus Publishers, 1977), pp. 5-7.

The Charbonneau Family in St. Louis

After the baptismal ceremony of 28 December 1809, little Jean Baptiste Charbonneau would have begun his schooling in St. Louis. Clark returned from Washington and offered Toussaint and Sacagawea a plot of farmland on which to settle in Missouri. But Charbonneau found farming was not to his taste, and sold the land back to Clark after a few months.[17]St. Louis Court Records show that Charbonneau bought a tract of land from William Clark on 30 October 1810, and sold it back on 26 March 1811 for $100. The land was in St. Ferdinand Township. See … Continue reading Toussaint Charbonneau and Sacagawea remained in the St. Louis area until 2 April 1811, when they headed upriver with a party of fur traders led by Manuel Lisa. Henry M. Brackenridge was traveling with Lisa on that voyage, and recorded that “We had on board a Frenchman named Charbonneau, with his wife, an Indian of the Snake nation, both of whom had accompanied Lewis and Clark to the Pacific, and were of great service. The woman, a good creature of a mild and gentle disposition, [was] greatly attached to the whites, whose manner and dress she tried to imitate, but she had become sickly, and longed to revisit her native country; her husband, also, who had spent many years among the Indians, was become weary of a civilized life.”[18]See the Journal of a Voyage Up the River Missouri, performed in 1811, by H. M. Brackenridge, in Thwaites, Early Western Travels (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904 ), Vol. VI, pp. 32-33.

Charbonneau served sporadically as an interpreter for the Indian Bureau at the Upper Missouri Agency from 1811 to 1838, making an average of $300 to $400 per year—very good money at that time. He carried out diplomatic errands for the United States among the Missouri River tribe during the War of 1812. He was not at Fort Manuel when Sacagawea died there in 1812. In 1815 he joined an expedition to Santa Fe, where he was briefly imprisoned by the Spanish for “invading” their territory.

As far as is known, after his 1809–11 visit Toussaint Charbonneau did not return to St. Louis until 1839, when he was described by Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joshua Pilcher as “tottering under the infirmities of 80 winters.”[19]This quote is from a letter of Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joshua Pilcher to T. Hartley Crawford, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, quoted at length in Stella M. Drumm, Journal of John C. Luttig … Continue reading He appeared in St. Louis to ask the Indian Bureau for back salaries. It is likely that Charbonneau lost his job as a government interpreter and his standing with the government upon the death of his patron, William Clark, in 1838. Pilcher’s was the last entry about Toussaint Charbonneau (discovered thus far) to appear in the official records. It is thought that Charbonneau died at about age eighty-six, sometime around 1843, for it was in that year that his estate was settled by his son, Jean Baptiste.[20]See Moulton, Vol. 3, footnote 1 on pp. 228-229 for a good summation of Toussaint Charbonneau’s life. See also Irving W Anderson, “A Charbonneau Family Portrait,” American West … Continue reading

Pomp’s Later Years

Little Pomp was left behind in St. Louis by his parents in 1811 and educated under William Clark’s guidance into the 1820s. He studied French and English, classical literature, history, mathematics, and science. In June 1823, eighteen-year-old Jean Baptiste met Paul William, Prince of Württemberg, on the Kansas River. The prince, traveling in America in much the same fashion as Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied would ten years later, convinced Toussaint Charbonneau to allow Pomp to return to Europe with him. As a result, Jean Baptiste lived for six years as a member of the prince’s royal household, receiving a classical education in Germany. He returned to Missouri in 1829, worked as a free trapper in Idaho and Utah, traveled with mountain men Jim Bridger, Jim Beckwourth and Joe Meek, and was a guide for the Mormon Battalion from Santa Fe to San Diego in 1846 during the Mexican War. He was briefly the alcalde (mayor) of Mission San Luis Rey in California and spent many years in the gold fields on the American River near Sacramento. It is doubtful that Jean Baptiste could have held his official position of alcalde without his baptism into the Catholic faith in 1809. Jean Baptiste probably did poorly in the California gold fields, for by 1861 he was listed as a clerk in the Orleans Hotel in Auburn, California. He headed for the newly opened Montana gold fields in 1866 but died en route, succumbing to pneumonia on May 16 in Inskip Station Oregon. He was sixty-one. His grave site is located in Danner, Oregon, three miles north of U.S. Highway 95.[21]See Anderson, especially pp. 14-19.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to The Charbonneaus in St. Louis:

Notes

| ↑1 | This is an extract from Bob Moore, “Pompey’s Baptism,” We Proceeded On, February 2000, Volume 26, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article with descriptions of traveling to St. Louis in 1808–09, the monastery on Monk’s Hill, and the religious life of St. Louis is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol26no1.pdf#page=13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), pp. 468-469. |

| ↑3 | The record is included in the Register of Baptisms of the Old Cathedral Parish. My research was conducted with the kind permission of Monsignor Bernard Sandheinrich, pastor of the Old Cathedral. |

| ↑4 | 17 August 1806, Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), Vol. 8, June 9-September 26, 1806. |

| ↑5 | See the letter of Pierre Chouteau to Secretary of War William Eustis, December 14, 1809, in The Territorial Papers of the United States, edited by Clarence Edwin Caner (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949), Vol. XIV, p. 343. Chouteau mentions writing a letter to Eustis (since lost) on 22 November 1809, after his arrival in St. Louis. The Missouri Gazette of 16 November 1809, reported Chouteau’s safe return. Pierre Chouteau, officially christened Jean Pierre Chouteau, was born in New Orleans in 1758 and along with his half-brother Auguste was a power in the frontier fur trade for most of his life. He died in St. Louis in 1849. For more on Pierre Chouteau, see William E. Foley and C. David Rice, The First Chouteaus (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983). |

| ↑6 | Three men were killed and eight wounded, including George Shannon, who had to have his leg amputated as a result of his wounds. See Nathaniel Pryor to William Clark, 16 October 1807, in Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962) pp. 432-438. |

| ↑7 | See Gov. Meriwether Lewis to Pierre Chouteau, 8 June 1809, and Pierre Chouteau to the Secretary of War, 14 December 1809, in The Territorial Papers of the United States, edited by Clarence Edwin Carter (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949), Vol. XIV, pp. 343-352. |

| ↑8 | Foley and Rice, pp. 143-148. |

| ↑9 | The one exception to this fact was the presence of an itinerant priest named Thomas Flynn from mid-1807 to January 1808. Flynn signed a contract with the St. Louis parishioners for a sum of money and provisions of food and drink to act as the parish priest for a period of one year. He was without orders to do so from his bishop, and resigned before his contract expired, after which he was lost to recorded history. |

| ↑10 | The monastery of La Trappe was founded in 1122, and made a branch of the Cistercian order in 1148. Trappist monks take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. They wear white robes instead of the traditional black or brown of most orders. |

| ↑11 | Monk’s Mound is today part of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, near Collinsville. It stands 100 feet tall and covers four acres of ground, the largest man-made structure built north of Mexico before the advent of the Europeans. |

| ↑12 | M.J. Spalding, Sketches of Early Catholic Missioners of Kentucky (Louisville, 1944 ). |

| ↑13 | See Rev. John Rothensteiner; History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis (St. Louis, 1928), Vol. 1, pp. 21 9-220. |

| ↑14 | Quoted in Rev. John Rothensteiner, History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Vol. 1, p. 219. |

| ↑15 | See Gregory M. Franzwa, The Old Cathedral (Gerald, Mo., The Patrice Press, 1980), for more on the history of the four buildings which have stood on the site of the Old Cathedral. The present Old Cathedral was built between 1831 and 1834. The vertical log church built in 1776 and standing in 1809 probably bore a strong resemblance and was similar in its dimensions to the still-standing Holy Family Church of Cahokia, Illinois, built in 1799. |

| ↑16 | See Mary B. Cunningham and Jeanne C. Blythe, The Founding Family of St. Louis (St. Louis: Piraeus Publishers, 1977), pp. 5-7. |

| ↑17 | St. Louis Court Records show that Charbonneau bought a tract of land from William Clark on 30 October 1810, and sold it back on 26 March 1811 for $100. The land was in St. Ferdinand Township. See Stella M. Drumm’s edition of Journal of a Fur-Trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri, 1812-1813, by John C. Luttig, originally published in 1920, republished in New York by Argosy-Antiquarian, Ltd., in 1964 on p. 138, and Russell Reid, Sakakawea: The Bird Woman (Bismarck: State Historical Society of North Dakota, 1986), pp. 14-15. Drumm also notes that Charbonneau purchased fifty pounds of bequit (biscuit or hard tack) from Auguste Chouteau on 23 March 1811, probably in anticipation of his trip up the river. |

| ↑18 | See the Journal of a Voyage Up the River Missouri, performed in 1811, by H. M. Brackenridge, in Thwaites, Early Western Travels (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904 ), Vol. VI, pp. 32-33. |

| ↑19 | This quote is from a letter of Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joshua Pilcher to T. Hartley Crawford, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, quoted at length in Stella M. Drumm, Journal of John C. Luttig (New York: Argosy-Antiquarian, Ltd., 1964 ), pp. 132-140. For reprinted excerpts from documents dealing with Charbonneau’s career as a government interpreter, see Chardon’s Journal at Fort Clark, 1954-1859, edited by Annie Heloise Abel (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997) pp. 278-282. |

| ↑20 | See Moulton, Vol. 3, footnote 1 on pp. 228-229 for a good summation of Toussaint Charbonneau’s life. See also Irving W Anderson, “A Charbonneau Family Portrait,” American West Magazine, March/ April 1980, especially pp. 13 and 16. |

| ↑21 | See Anderson, especially pp. 14-19. |