No one is certain who applied his name to the Pryor Mountains, Pryor’s “gap,” and the town of Pryor, Montana, nor when.

Pryor Creek joins the densely braided Yellowstone River from the south (the viewer’s left; the Yellowstone is flowing toward the viewer), fifteen or sixteen miles below the point where it is believed Pryor crossed the Yellowstone, at today’s Billings, Montana. Pryor Creek begins about fifty straight-line miles away, in Pryor Gap in the Pryor Mountains, but coils into nearly 100 miles of creek bottom by the time it empties into the Yellowstone.

Local Lore

Local lore maintains that Pryor traveled up this creek to the mountains, that he “drew the mountains and the creek on the map he was making,” and “decided to name them both in honor of himself.”[1]Pryor Clan History (n.p.: Pryor, Montana, 1973), 2. Not only is there no evidence whatsoever in the expedition’s journals that he explored the creek, but also it would have been entirely inconsistent with his modest character to have named anything after himself. In any case, he would have passed north of today’s Pryor Mountains. Besides, Clark didn’t cross the creek he named for Pryor until the day after they went their separate ways, so he didn’t even know its name when he crossed it.[2]When Pryor reported to Clark, sans horses, on 8 August 1806, the captain recorded: “he passed one Small river which I have Called Pryors river which [rises] in a Mtn. to the South of Pompys … Continue reading George Drouillard, who returned to the Yellowstone with Manuel Lisa‘s fur trading party in 1807, followed part of it.

Pryor Mountain Horses

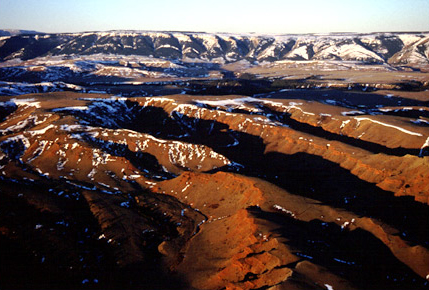

East Pryor Mountain (elevation 8,822 ft) dominates the horizon. In the foreground is Yellowtail Reservoir, in the Big Horn River Canyon. Pompeys Pillar is about 60 miles to the right (north-northeast) of this photo.

On the south slopes of East Pryor Mountain roams a herd of 159 (as of March 2002), wild horses. Dozens of herds, actually—mature stallions with their mares and colts, and young ones hanging out with their peers, all following spring greenup from the foothills to the high ridges and meadows, or retreating from winter’s winds into the deep draws of the badlands along the Bighorn River. It is of course impossible to say whether any of those mustangs are descendants of the horses taken from Nathaniel Pryor back in July 1806.[3]The scientific name for the domestic horse is Equus caballus. The name of the genus, equus, is Latin for “horse”; the name of the species, caballus, is Latin for “riding … Continue reading

The Crows—if that’s who took them—could not have had any reason to keep them separate from the rest of their horses. Besides, the animals Pryor was responsible for had been bought cheap by the Corps’ captains from Lemhi Shoshones, Nez Perces, and lower Columbia River Indians.

In any case, DNA evidence indicates that, like all the other feral horses in the Western United States, the Pryor Mountain horses are descendants of Spanish Barbs, or “Barbery horses” bred by the Berbers of North Africa.[4]See http://www.imh.org/imh/bw/sbarb.html brought to the Americas as early as 1493. Sometime after the beginning of the 18th century, Plains Indians acquired Spanish horses through trade, or by culling them out of stray herds.

The fenced, 38,000-acre Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range, established in 1968, was the first of three federal “special status areas” for feral horses.[5]The population figure for feral horses cited above includes wild burros. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals (Rev. ed., New York: Knopf, 1996), 810–13. The other two ranges, designated in the Wild Free-roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, are located on the Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada and near Grand Junction, Colorado. All three are administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management. In addition, the BLM oversees 209 other “herd management areas” that cover about 35 million acres of public land in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon and Utah, and, as of 11 June 2014, contained an estimated 40,815 feral horses and 8,394 burros.[6]Wild Horse and Burro Advisory Board, On Range Report, 23 April 2015 (US Bureau of Land Management) … Continue reading

To maintain healthy ranges, which in many places are shared with cattle, the BLM makes some wild horses available for adoption every year, so there are now privately owned herds in many other states. Also, historic herds of a somewhat smaller breed of wild horses totaling about 150 animals have survived for perhaps 300 years on Assateague Island, off the coasts of Virginia and Maryland.

Wild horses are mentioned twice in the journals of Lewis and Clark. On 5 July 1806, having recently crossed the “east fork of Clark’s river” at today’s Missoula, Montana, Lewis noted: “there are many wild horses on Clarkes river. About the place we passed it we saw some of them at a distance. There are said to be many of them about the head of the yellowstone river.” And in the monumental “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” which included several mountain tribes, there were “La Playes,” a wandering people whose country, from the heads of the Arkansas and Red Rivers eastward to “the gulph of Mexico,” was said to abound in wild horses.[7]Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450.

Notes

| ↑1 | Pryor Clan History (n.p.: Pryor, Montana, 1973), 2. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | When Pryor reported to Clark, sans horses, on 8 August 1806, the captain recorded: “he passed one Small river which I have Called Pryors river which [rises] in a Mtn. to the South of Pompys Tower.” |

| ↑3 | The scientific name for the domestic horse is Equus caballus. The name of the genus, equus, is Latin for “horse”; the name of the species, caballus, is Latin for “riding horse.” The word feral comes from the Latin fera, meaning “wild animal”; mustang is from the American Spanish word mestengo, meaning “stray animal.” |

| ↑4 | See http://www.imh.org/imh/bw/sbarb.html |

| ↑5 | The population figure for feral horses cited above includes wild burros. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals (Rev. ed., New York: Knopf, 1996), 810–13. |

| ↑6 | Wild Horse and Burro Advisory Board, On Range Report, 23 April 2015 (US Bureau of Land Management) https://www.blm.gov/style/medialib/blm/wo/Planning_and_Renewable_Resources/wild_horses_and_burros/statistics_and_maps/advisory_board_documents.Par.71122.File.dat/OnRange%20Report_Fuell_Advisory%20Board%202015.pdf accessed on 15 March 2017. |

| ↑7 | Moulton, Journals, 3:386-450. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.