Up with my Tent, heere will I lye to night. But where to morrow?

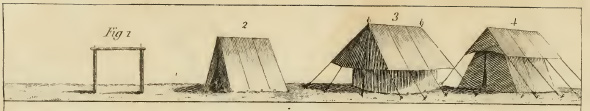

Bell Tents

Grose’s Military Antiquities of 1801[2]Francis Grose, Military Antiquities Respecting a History of the English Army from the Conguest to the Present Time (London: T. Egerton, Whitehall, & G. Kearsley, Fleet Street, 1801), facing page … Continue reading

PLATE 3. Called bell-tents, colour-stand, and camp-kitchen. Fig. 1. A bell-tent viewed in the front. 2. The same seen in the rear. 3. The centre pole with the cross for supporting the arms. (Grose, 2:233)

Modern Tents[3]Francis Grose, Military Antiquities, facing page 37, plate 1.

Grose’s Military Antiquities of 1801

PLATE 1. Fig. 1. The tent poles of a private tent. 2. A private tent. 3 and 4. Fly tents. (Grose, 2:233)

Foxes had holes, birds had nests, but Lewis and Clark had no tents. Deep in the unexplored wilderness of North America at a critical stage in their historic voyage of discovery, the two captains with their 31 companions found themselves completely destitute of shelter. By July 1805, near the Great Falls of Montana, the customary tenting which was part of their original equipage was gone; it had either become useless, or for other unknown reasons, simply was missing. Thus, only three months outbound from comfortable winter quarters at Fort Mandan—more than a year beyond the departure from St. Louis—the explorers would have to face the hardships of the Rocky Mountains without overhead protection. Until then they had had only a brief taste of the harsh climate, weather and terrain which awaited them-lightning, wind, sand, mud, cactus, hail, snow, rain, rain and more rain. On 7 July 1805, while preparing to proceed up country from the falls, Meriwether Lewis brooded over his situation:

“we have no tents . . . we have not more skins than are sufficient to cover our baggage . . . many of the men are engaged in dressing leather to cloathe themselves their leather cloathes soon became rotten as they are much exposed to the water and frequently wet.”[4]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986) 4:365. All quotations from, or references to, Journal entries in the … Continue reading

With no tents in this area at this season, Lewis must have felt like the helmsman of a sinking ship, caught at sea with no life boats. One who follows his traces is driven to wonder how such a critical item as shelter could then be missing from the equipage. For background on Lewis’s predicament and subsequent sheltering of the expedition, one must turn to his original plans for the initial outfitting of the Corps of Discovery.

Tent Requirements

While in Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, Lewis clearly had foreseen the rigors of weather which would be encountered on a planned two year “campaign.” He carefully provided, as any military commander would, for appropriate protection for his soldiers. His initial list of requirements included specific details for shelter. Donald Jackson’s compilation of the pertinent records reflect these preparations:[5]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:71,90.

Outfitting the Expedition

Lewis’s List of Requirements

Camp Equipage (excerpt)

“40 Yds [oil Linnen] To form two half faced Tents or Shelters contrived in such manner their parts may be taken to pieces & again connected at pleasure in order to answer the several purposes of Tents, covering the Boat or Canoe, or if necessary to be used as sails. The pieces when unconnected will be 5 feet in width and rather more than 14 feet in length.”

Supplies from Private Vendors (excerpt)

| Mr. Israel Whelan 1803 June 15 |

To richd. Wevill Dr. |

| To 107 yds of 7/8 brown Linen @ 1/6 | 21.40 |

| To 46½ yds of 7/8 Flanders Sheeting @ 2/5 | 14.49 |

| To 10 yds of 7/8 Country Linen 3/ | 4.– |

| To making the brown Linen into 8 Tents, with Eyelet-holes, laps, &c Thread &c. | 16.– |

| To making the Russia Sheeting into 45 Bags. Thread &cord. @ 1/6 | 9.– |

| To 2 Gross of Hooks & Eyes @ 3/9 | 1.– |

| To Oiling all the Linen & Sheeting— 150 Square Yards @ 2/6 |

52.– |

| To numbering all the Bags & Tents | 1.50 |

| $119.39 |

By these dimensions each of the two pieces of such a tent would consist of 70 square feet, or a total of 140 square feet for the two pieces, i.e. 15.55 square yards. Thus two oil-cloth tents, each 14 feet long, would be produced out of the above 40 yard requirement with 10 yards left over. Considering that standard military tents for private soldiers of the Revolutionary era[6]Harold L. Peterson, The Book of the Continental Soldier (Harrisburg. Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company, 1968), re “Tents.” were less than half as long as the above specifications and could hold up to five men each, Lewis’s two out-sized tents would have provided ample protection and baggage cover for the originally planned party of 15 men. However, cost records of Lewis’s actual purchases reflect that considerable additional yardage beyond the initial 40 yard requirement was procured. Much greater flexibility and tent capacity was thereby provided than would have been possible with only two of the above described tents. Could Lewis, even at this early date, have been anticipating a tent need for additional soldiers to be later added to his complement? Absent any record of further shelter acquisition later in the journey, either at St. Louis or elsewhere, it is intriguing to note that the purchases made in Philadelphia could have sufficiently sheltered the Corps even after the number of soldiers had been doubled at Camp Dubois. The tabulation of costs as billed by “Richd. Wevill,” the Philadelphia upholsterer doing the work (excerpted from Jackson’s compilation above), together with calculations made above indicate this possibility:

| Item | Sq. Yds. (approx.) |

|---|---|

| A. 2 “half-faced” tents meeting Lewis’s specs as in Jackson, Letters, Camp Equipage above, i.e. 15.5 sq. yds. per each 2-piece tent |

31 |

| B. 6 tents per dimensions customary for private soldiers of the era (i.e. 2 pieces 6.5′ x 6.5′ ea. per tent) to accommodate as many as 5 soldiers each, 9.4 sq. yds. per tent | 56 |

| C. “Remainder” of “Brown Linen” per Jackson, Letters, Supplies from Private Vendors above | 20 |

| Total square yardage of “Brown Linen” per Jackson, Letters above | 107 |

This recap indicates that eight tents were made out of the 107 yards of “brown linen.” Clearly, all eight of those tents could not have been of the dimensions Lewis described for the two “outsized” tents as reported in Camp Equipage above. This would have required more than 120 yards (i.e., 8 x 15.5 sq. yds.). An additional summary itemization in Jackson indicates the addition of a “common tent” beyond the purchases through Wevill, and also shows 20 yards of brown linen beyond the 107 yards used for fashioning the eight tents. On an assumption that Lewis would not have abandoned his initial idea of having two “outsize” half-faced tents (for baggage cover, sails, etc.) in addition to personnel tents for the enlisted men, the purchase records itemized above can be reconciled, “figuratively” at least.

By these calculations Lewis would have had rwo large tent-like coverings for the boat and baggage (alternatively usable as sails but ordinarily not for personnel use, unless on board the keelboat)[7]The dimensions Lewis prescribed for such a tent (i.e. two halfs each 5′ x 14′) would not be the most comfortable for personnel use. If the sides of such tent were to reach to the ground … Continue reading plus 6 tents for the enlisted men, ultimately allowing two tents (each capable of holding as many as five soldiers) for each of the three separate “messes” later established. thus making a total of the eight tents in the Purveyor’s list-with a safety margin of an extra 20 square yards for other adaptations en route. The additional “common tent” is identified in Jackson as an item “received from the Arsenal for the use of Capt Lewis May 18th, 1803.” This was an item “of issue” from military stores as distinguished from a purchase on the open market through a Purveyor. It could have been a “Fly tent” such as shown in “Grose’s Military Antiquities of 1801” (see illustration herein) and may have been the item which the captains occasionally referred to in their writings as “our tent” (at least on the voyage as far as Fort Mandan). At any rate it is evident by these preparations that Lewis had carefully anticipated the need to shelter his men, as well as the precious implements of the voyage, from wind, rain, hail and snow while in transit across the continent.

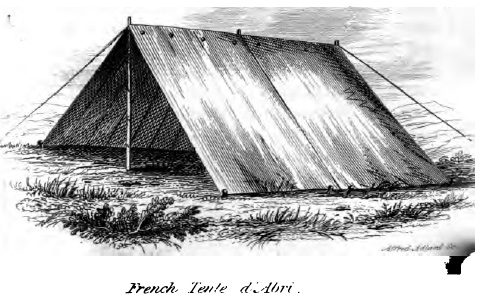

French Tent d’ Abri

Godfrey Rhodes, Tents and Tent-Life, facing page 158.

From Godfrey Rhodes’ Tents and Tent-Life, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time:

The Tente d’ Abri, or “tent of cover,” consists of a series of pieces of hempen canvas, having buttons sewn on along one side at about 8 inches off the edge, and button-holes made close to the same edge, at the same end of the canvas; at the other two corners of the sheet is fastened a short loop of rope, which is used to secure the canvas to the pegs when the tent is pitched. The size of each sheet is 5 feet 8 inches by 5 feet 3 inches. As this tent is intended to serve as a temporary bivouac-cover for troops on the march, a portion is allotted to be carried by each soldier. This portion consists of one hempen canvas sheet, three small wooden pegs, and one round stick 4 feet 4 inches long by 1½ inch in diameter; the total weight is 3½ lbs. This tent is generally constructed by joining either three or six portions together; one portion affording cover to one soldier. The method of construction is by overlapping the sides of two sheets, and then buttoning them together; thus, when the tent is pitched, a row of buttons appears on the outside near its top, and another row of buttons on the inside, but as the two sides overlap, this latter row is on the opposite inside slope of the tent. A stick or short pole, as above described, supports the canvas at each end; the two sheets, now buttoned together, are stretched out, and by means of the two small loops of rope attached to each corner are pegged to the ground. To further strengthen the tent, a rope is secured to the top of each pole, stretched out, and pegged to the ground. This triangular-shaped tent (for three soldiers) stands 4 feet high, by 7½ feet in width. To close up one of the triangular openings a third canvas sheet is used consequently a third pole is not requisite, and can be dispensed with, but the three extra pegs are useful in case of loss or breakage. One end is open.

In constructing a Tente d’ Abri for six men, four sheets of canvas are used for the tent covering, the two remaining, close the triangular openings at each end; a third pole supports the canvas in the middle, consequently no more than three poles and ten pegs are actually requisite to pitch a six-sheet tent, having the ends closed up; but if the six sheets are used for the covering (leaving both ends open) four poles and fourteen pegs are requisite, leaving two poles and four pegs to spare.[8]Godfrey Rhodes, Tents and Tent-Life, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time, to Which is Added the Practice of Encamping an Army in Ancient and Modern Times (London: Smith, Elder, and Co. … Continue reading

Travel Time

As matters turned out, Lewis would be “on the move” more than two-thirds of the total time of the expedition. His permanent party would be in travel status almost as long. The table below summarizes the number of nights in which the corps (i.e. the contingent moving with Lewis) had no real roof overhead-no established weather-proof shelter.

| Number of "Shelter Nights" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corps Status | Date* | Stationary Quarters | Temporary "in transit" Shelter (if any) | Total |

| Lewis left Pittsburgh by boat | 31 August 1803 | — | 122 | 122 |

| Party moved into huts constructed at Camp Dubois | 30 December 1804 | 129 | — | 129 |

| Party embarked from Camp Dubois[9]They moved into tents, but would not leave Camp Dubois until May 14.—ed. | 9 May 1804 | — | 195 | 195 |

| Party moved into huts constructed at Fort Mandan | 21 November 1804 | 137 | 137 | |

| Party embarked from Fort Mandan | 6 April 1805 | — | 263 | 263 |

| Party moved into huts constructed at Fort Clatsop | 24 December 1805 | 88 | — | 88 |

| Party embarked from Fort Clatsop | 23 March 1806 | — | 184 | 184 |

| Party arrived at St. Louis | 23 September 1806 | — | — | — |

| Total "shelter nights" | 354 | 764 | 1118 | |

| *Dates have been arbitrarily selected from varying dates given in the journals | ||||

Boats As Shelter

One might argue from the table above that the Ohio/Mississippi river leg of the voyage, from Pittsburgh to St. Louis, should be excluded from the “roofless” nights on grounds that the keelboat was in effect a houseboat. The officers, when on board, doubtless occupied the cabin; the oil-canvas tent-covers stretched over the deck could shield the 12 or more other passengers when necessary. Lewis’s journal entry of 9 September 1803 while the boat was near Bellaire, Ohio indicates his regular use of boat facilities for shelter—”the rain came down in such torrents . . . when I wrung out my saturated clothes, put on a dry shirt turned into my birth” [emphasis added]. The boat probably served as regular quarters for the officers only (and generally as command post) at Camp Dubois and up the Missouri to the Knife River Villages. Lewis noted on 20 May 1804 “at an early hour I returned to rest on the boat,” and 17 September 1804, “Having for many days past confined myself to the boat, I determined to devote the day to amuse myself on shore . . . “

Beyond Fort Mandan, during later stages of the voyage, whenever travel was by water, the pirogues offered special, emergency cover when necessary. Thus:

- 12 June 1804, Clark: “The interpreters wife verry sick so much so that I move her into the back part of our Covered part of the Perogue . . .

- 25 July 1806, Ordway: “rained verry hard and we having no Shelter Some of the men and myself turned over a canoe & lay under it.”

- 6 August 1806, Lewis in a violent storm: “our situation was opened and exposed . . . I got wet to the skin and having no shelter on land I betook myself to the orning of the perogue . . . formed of Elkskin. here I obtained a few hours of broken rest . . . “

- 11 August 1806, Lewis suffering a high fever from his accidental gun shot wound: “as it was painfull to me to be removed I slept on board the perogue.”

Tent Routine

During the river passage from Camp Dubois to the Mandan villages, though the officers may generally have been lodged on the boat, the enlisted men camped on shore. They seem to have had militarily acceptable shelter-using the tents described above which were part of the original equipage. Organized in three separate messes, each under the charge of a sergeant, they observed a daily order of encampment: “Tents Fires and Duty.”[10]Moulton, 2:332-3n2. By detachment orders of 26 May 1804, the sergeants were relieved of these duties and were to see that their men performed “an equal propotion” of such tasks. A further order of 8 July 1804 named a private in each mess as “Superintendant of Provision” and relieved these men also from pitching tents. When movement delays of several days occurred, camp sites and routines were more formal occasions such as:

- 27 June 1804: a pause at confluence at the mouth of the Kansas River

- 30 July 1804: meetings with the “Otteaus” near Council Bluff

- 25 September 1804: meetings with the Teton Sioux near the mouth of the Teton River

- 29 October 1804: meetings with the Mandans

At these times the officers’ tent and an “orning” (awning) would be erected, a flag planted in front, a parade held or an inspection conducted. The headquarters tent was the focal point of the camp. The oil-cloth canvas used as sails or baggage coverings served as “orning” to provide shade for ceremonial meetings and council talks with native chieftains.[11]Supplementing Editor Moulton’s notes, the author is indebted to Robert F. Morgan of Clancy, Montana, well-known history illustrator, for comment by letter 25 November 1994 on background … Continue reading

The two captains throughout the expedition variously referred to “our tent,” “my tent,” and “our Lodge.” Rather than relating to a single piece of equipment, these references clearly indicate different shelters at different times. Three possibilities: (1)the “common tent” reported in Lewis’s acquisitions in Philadelphia, probably “our tent” used when the officers camped on shore during the voyage from St. Louis to the Mandan villages, (2)the “leather Lodge” carried from Fort Mandan westward (of which more later herein), and (3)lodges or “tents” erected for the captains by their native hosts, for example when with the Lemhi Shoshones and Nez Perces.

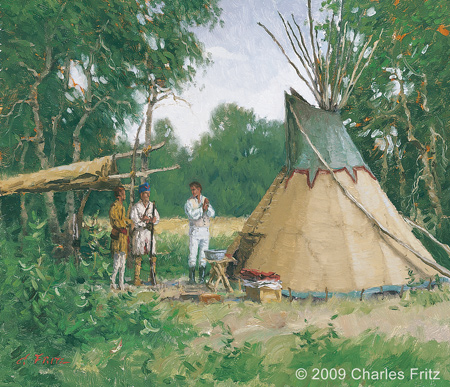

The Leather Lodge

Our Captains’ Hide Lodge

12″ x 14″ oil on board

© 2009 by Charles Fritz. Used by permission.

The “Leather Lodge,” which had a dramatic separate history of its own, first comes on stage on 7 April 1805-the day after the Corps left Fort Mandan westbound. Lewis recorded that:

Capt. Clark myself the two Interpreters and the woman and child sleep in a tent of dressed skins. this tent is in the Indian stile, formed of a number of dressed Buffaloe skins sewed together with sinues [sinews] . . . to erect this tent, a parsel of ten or twelve poles are provided. fore or five of which are attached together at one end, they are then elevated and their lower extremities are spread in a circular manner to a width proportionate to the demention of the lodge, in the same position orther poles are leant against those, and the leather is then thrown over them forming a conic figure.

Moulton notes that this “tent” was “obviously a plains Indian tipi.”[12]Moulton, 4:12n8. It appears to have been acquired from Charbonneau at Fort Mandan; Clark referred to it in his record of 17 August 1806 (when Charbonneau was paid for his services, at the conclusion of the journey at Fort Mandan) stating that the settlement payment of “500 $ 33-⅓ tents” included the price of the “Lodge purchased of him for public service.”

The lodge had a charmed life, surviving accidental destruction at least three times. On 17 May 1805, Lewis related that “we were roused late at night by the Sergt of the guard” when a large tree caught fire immediately over the lodge; “we had the loge removed, and a few minutes after, a large proportion of the top of the tree fell on the place the lodge had stood; had we been a few minutes later we should have been crushed to attoms.” The burning coals from the fire flew all about the camp, harassing the awakened men nearby and inflicting “considerable injury” to the lodge. Eleven days later, on the 28th, it was again threatened. In the deep of night a stray buffalo charged maddeningly straight toward the lodge-diverted from crashing into it just in the nick of time by Lewis’s dog Seaman.

Thus baptized by fire east of the Continental Divide, the lodge went through total water immersion west of the Bitterroots. On 14 October 1805 one of the new canoes, carrying the lodge downstream from “Canoe Camp,” filled and sank in the Snake River. A number of articles floated out, Clark reported, “Such as the mens bedding Clothes and Skins the Lodge &c. &c.” Most of the articles, including the lodge, were “Caught by 2 of the Canoes.” But weather and hard use during the ensuing weeks would damage the lodge more than the hazards of fire, stampede and immersion. By November 28th, in the aftermath of wind and hard rain, Clark recorded:

” . . . we are all wet bedding and Stores. haveing nothing to keep our Selves or Stores dry, our Lodge nearly worn out. and the pieces of Sales & tents so full of holes &. rotten that they will not keep any thing dry . . . aded to this the robes of our Selves and men are all rotten from being Continually wet and we Cannot precure others, or blankets in their places.”

Despite the sad state of their shelter the captains tried to get further use out of the lodge. At the mouth of the Columbia, 13 December 1805, while preparing to construct Fort Clatsop in the incessant rain, Clark described the leather lodge as “So rotten that the Smallest thing tares it into holes and it is now Scarcely Sufficient to keep the rain off a Spot Sufficiently large for our bead [bed]!” Nevertheless, once settled in timbered quarters at Fort Clatsop, Lewis would cling to a hope for further use of this seemingly worthless shred-“dryed out lodge” he wrote, “and had it put away under shelter.” On the homeward journey however, by 15 May 1806, he had given up such hope. As the party paused with the Nez Perce, waiting for the mountain passes to open, the captains “had a bower constructed . . . under which we set by day and sleep under the part of an old sail now our only tent as the leather lodge has become rotten and unfit for use.” To the reader, it had seemed unfit long, long ago; shall it be said that the lodge just faded away? or was it stretched even further, following the Indian practice of recycling old used-up tipi leather into moccasins and other clothing?

“No Tents”

The tale of the captains’ tent is a paradigm For the broader story of the travel shelters of the expedition. It is a story evoking profound pity on the one hand for the travelers (including a teen age girl and baby), nakedly exposed to the most miserable weather, and on the other, awe in how they managed to survive through it. Yet there remains an air of mystery as to why the corps was caught short on shelter from the Great Falls onward, at the worst times of the nomadic stages. Here is a sampling of the misery endured:

| Date | Place | Journal Notation |

|---|---|---|

| 4 June 1805 | Marias River (small scouting detachment) |

Lewis: “It rained this evening and wet us to the skin; the air was extremely could” |

| 6 June 1805 | Marias River (small scouting detachment) |

Lewis: “it continues to rain and we have no shelter.” |

| 7 June 1805 | Marias River (small scouting detachment) |

Lewis: “we left our watery beads at an early hour” |

| 7 July 1805 | Main party at Great Falls portage site |

Lewis: “we have no tents” |

| 17 December 1805 | Main party near mouth of the Columbia |

Clark: “a most dreadful night rain and wet without any Covering . . . Certainly one of the worst days that ever was!” |

| 17 July 1806 | Clark’s advance party on the Yellowstone |

Clark: “The rain of last night wet us all [Nicholas Biddle: having no tent, & no covering but a buffaloe skin]” |

Why did this condition exist? Though the “Lodge” continued to be carted along in the baggage, the enlisted men’s “tents” are mentioned hardly at all in the post-Mandan journals. As noted above, these tents were either unusable by June 1805 or had been deliberately abandoned. Surely they could have been sufficiently replaced, by skins from the thousands of buffalo and elk encountered in the prairies, to provide ongoing shelter and a reserve for personal cover. More likely, however, a calculated risk may have been taken-that nature itself would provide for their needs as they went along. This indeed proved to be the case, though with harrowing results.

Very evidently cargo weight was a major factor. In early June when the first complaints of “no tents” occur, the party was stalled at the junction of the Marias and the Missouri reconnoitering for the correct route. Then and there the captains started to get rid of weight. “We determined to deposite at this place,” Lewis wrote on 9 June 1805, “the large red perogue all the heavy baggage which we could possibly do without . . . with a view to lighten our vessels . . . ” He gives an inventory of “articles to be deposited” bur there is no reference therein to burying any tents. A week later, 16 June 1805, at the lower portage site of the Great Falls, the parry again threw our ballast-“we determined to leave the white perogue at this place . . . and also to make a further deposit of our stores.” Again an inventory is made, but again no mention of tents. (At least two other inventories of goods and provisions are available in the journals: One, a list of “necessary stores,” found in a journal sent back from Fort Mandan; also Clark’s list prepared 16 March 1806 on “the State of our Stock of Merchandize . . . a scant dependence indeed . . . “[13]Ibid., 3:500-04. None of these listings bear any clue as to specifically what happened to the soldiers tents.)

Tent Weight

The glimpse of Lewis on 3 June 1805 preparing for a soggy tramp up the Marias River offers an idea of what goes through one’s mind while contemplating living out of a backpack on any prolonged foot journey, whatever weather might occur. Lewis wrote:

I had now my sack and blanket happerst [i.e. an Indian knapsack] in readiness to swing on my back, which is the first time in my life that I had ever prepared a burthen of this kind, and I am fully convinced that it will not be the last . . .

The reader does not know what was in this “burthen,” but assuredly there was no tent. And with good reason-a tent of the sort described earlier above would be bulky and heavy-something no hiker would want stuffed in his pack. Tents such as those which the party had transported up the Missouri would weigh at least eleven pounds when dry.[14]Edward S. Farrow, Military Encyclopedia, (New York: Military-Naval Publishing Company,1895, Second Edition), 1:422,423 re “tentes d’abri” (see illus. in text herewith). We may speculate that Lewis and crew considered this paraphernalia (if then available in the equipage) as part of “all the heavy baggage which we could possibly do without.” From the Marias onward, for personal shelter it was thus largely every man for himself.

The Hard Cold Ground

Neither the captains nor their men were unacquainted with the bare ground. Not infrequently, members of the party had been unexpectedly stranded away from their peers, without cover of any kind. A few samples:

- 2 June 1804, Drouillard and Shields: “had been absent 7 days Swam many creeks. much worsted”

- 23 June 1804, Clark unable to join the boat in a wind storm, camped alone overnight: “Peeled some bark to lay on.”

- 25 August 1804, Visiting the “mountain of “evel Spirits,” both Lewis and Clark with 9 others were caught in a rain storm too far away from camp: “Concluded to stay all night . . . on a Bujfalow roabe we Slept verry well . . . ” (how many on one robe?!)

- 20 December 1804, Lewis, out hunting for buffalo, spent: “a Cold Disagreeable night . . . in the Snow with one Small Blankett . . . “

That the enlisted men regularly stretched out on the ground without overhead shelter is seen in the “uproar” caused by the stampeding buffalo, noted above, when the officers had to move their lodge. The “large Bull” ran “full speed directly towards the fires, and was within 18 inches of the heads of some of the men who lay sleeping . . . ” in ranges before the fires. Again, on 15 November 1805, while complaining of eleven days of continuous rain, Clark reported that Indians nearby during a previous night had stolen the guns of Shannon and Willard “from under their heads”-a feat not probable had the men been under overhead cover.

Blankets

Blankets, whether of wool or of leather skins, became the sole means of protection -. Blankets were measured by a system of “points,” prevalent among traders of the era.[15]Moulton, 5:131n1, quoting Charles E. Hanson, “The Paine Blanket,” The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly, Vol. 12, pp. 5-10 (Spring 1976). The captains refer twice to “2-½ point blankets” among the Shoshone, for example, Lewis notes their robes were “generally about the size of 2-½ point blanket.” And at the mouth of the Columbia. Clark observed of the natives on 21 November 1806 that many of them had 2-½ point blankets. Such blankets would be “5 feet 4 inches by 4 feet 3 inches and weight 3-1/16 pounds.” By the itemizations in Jackson, the blankets used by the Corps were 3 point, thus heavier; but even these were hardly adequate. On 2 August 1805, despite intense daytime heat, Lewis said the nights were “so could that two blankets are not more than sufficient covering. ” Moreover, substitute leather blankets had to be replaced often because of rot. On 7 November 1805, Clark bought two beaver skins to make a robe “as the robe I have is rotten and good for nothing.” Elk and buffalo skins were the principal sources for blankets and clothing, but often were soaking wet and easily infested with vermin. With no other choices available, the adage that “home is where your bed is”[16]Lynne Lamberg, Guide to Better Sleep, the American Medical Association, (New York: Random House, 1984), 3. became “home is your blanket.”

Alternative Shelter

It was catch-as-catch-can each night to find a place to stretch out and wrap up, always conscious of the possibility of rain, hail and snow. The range of such shelter possibilities included:

- 14 June 1805: “a few sattering cottonwood trees“

- 29 June 1805: “A deep rivene where there were some shelving rocks . . .”

- 10 November 1805: “the logs on which we lie is all on flote every high tide . . . we are all wet”

- 11 November 1805: “in the Crevices of the rocks &. hill Sides”

- 15 November 1805: “Huts made of boards . . . found” at an abandoned native village

Homebound

Both on the approach to the mouth of the Columbia in November and December 1805 and after departing from Fort Clatsop in March 1806, the party frequently camped in or near old villages, abandoned or vacated by natives. But these quarters were barely acceptable because of mice, vermin and Fleas. Accommodations did improve at Long Camp with the Nez Perce though only after frustrating experience with a “grass” tent which Clark expected “to turn the rain completely.” He learned, however, after an all night rain 16 May 1806, that “the water passed through flimzy covering and wet our bed most perfectly . . . we lay in the water all the latter part of the night,” and their chronometer got soaked! A few days later, 21 May 1806, after more soaking, the Captains “had a lodge constructed of willow poles and grass in the form of the orning of a waggon closed at one end.” On a happier note, Lewis reported that this new lodge was “perfectly secure against the rain sun and wind” and afforded “much the most comfortable shelter we have had since we left Fort Clatsop.”

After the four week sojourn with the Nez Perce, the moving caravan seems to have had fewer shelter difficulties. There were occasions indeed when cottonwood clumps, rock crevices, and abandoned “stick lodges” became overnight refuges in bad weather. Returning again to the plains the men were able, as Lewis reported on 11 July 1806, to bring in “as many buffalo hides as we wanted to canoe cover, shelter & geer.” Either such new provisions were sufficient for their needs or the men were so inured to hardships, or so enthralled with the down-river run toward home that very few references to shelter occur in the record. But on the final leg of the journey, on encountering James Aird (a trader heading up river on 3 September 1806) Clark relished the opportunity to enjoy real shelter in a violent storm-“I set up late” he wrote, “and partook of the tent of Mr. Ajres which was dry” [italics added]. And on September 20th the party met “2 Scotch gentlemen” near the village of Charriton on the Missouri. The captains then had a final chance en route to remember what camp comfort could really be: “as it was like to rain,” Clark wrote, “we accepted a bed in one of their tents.” The enlisted men also could enjoy real beds for a change. “Several of them had axcepted of the invitation of the Citizens and visited their families,” the journals state on the 21st; and, on the 22nd the party was “all sheltered in the homes of those hospitable people.” From then on, they could think, there would be no more holes to crawl in, nor crevices to creep under, nor flea blankets to wrap up in. They could dream, as they went their separate ways, of snug cabin homes with warm firesides in winter, and cool porch breezes in summer-no lingering thoughts of tents (except perhaps, those known as “mosquito-biers” on hot summer nights back in the “U. States”)! . . .

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Tent Shreds & Pieces: Nomadic Shelter on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”, We Proceeded On, February 1996, Volume 22, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol22no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Francis Grose, Military Antiquities Respecting a History of the English Army from the Conguest to the Present Time (London: T. Egerton, Whitehall, & G. Kearsley, Fleet Street, 1801), facing page 37. |

| ↑3 | Francis Grose, Military Antiquities, facing page 37, plate 1. |

| ↑4 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986) 4:365. All quotations from, or references to, Journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, Volumes 1 – 8, by date unless otherwise indicated, without further citations in these notes. |

| ↑5 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:71,90. |

| ↑6 | Harold L. Peterson, The Book of the Continental Soldier (Harrisburg. Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company, 1968), re “Tents.” |

| ↑7 | The dimensions Lewis prescribed for such a tent (i.e. two halfs each 5′ x 14′) would not be the most comfortable for personnel use. If the sides of such tent were to reach to the ground to shield off weather. the center pole (by Pythagorean calculations) could not be more than 4 feet high; this configuration would offer an entrance of only 6 feet in width at ground level-awkward enough to say the least). |

| ↑8 | Godfrey Rhodes, Tents and Tent-Life, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time, to Which is Added the Practice of Encamping an Army in Ancient and Modern Times (London: Smith, Elder, and Co. Cornhill, 1858), 157–158. |

| ↑9 | They moved into tents, but would not leave Camp Dubois until May 14.—ed. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, 2:332-3n2. |

| ↑11 | Supplementing Editor Moulton’s notes, the author is indebted to Robert F. Morgan of Clancy, Montana, well-known history illustrator, for comment by letter 25 November 1994 on background for his paintings of expedition episodes, particularly that of the terminal camp of the portage site. |

| ↑12 | Moulton, 4:12n8. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., 3:500-04. |

| ↑14 | Edward S. Farrow, Military Encyclopedia, (New York: Military-Naval Publishing Company,1895, Second Edition), 1:422,423 re “tentes d’abri” (see illus. in text herewith). |

| ↑15 | Moulton, 5:131n1, quoting Charles E. Hanson, “The Paine Blanket,” The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly, Vol. 12, pp. 5-10 (Spring 1976). |

| ↑16 | Lynne Lamberg, Guide to Better Sleep, the American Medical Association, (New York: Random House, 1984), 3. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.