© 2023 by Steve Ludeman, www.steveludemanfineart.com. Used by permission.

In mid-December 1803, construction of winter quarters begins. In accordance with the wishes of the Spanish Governor, Lewis could work in St. Louis and the soldiers could build a garrison at Wood River across from the mouth of the Missouri. The cantonment is known today as Camp River Dubois.

In St. Louis, Lewis learns about the Missouri River from established St. Louis traders and purchases more Indian gifts and equipment from local merchants. Across the river, the captains would need ot establish military discipline and the soldiers would need to become a team.

Both captains and key personnel cross the Mississippi frequently, and in March, Lewis and Clark witness the official transfer of Upper Louisiana from Spain to France. One day later, France transfers the territory to the United States.

With the arrival of several St. Charles French boatmen from St. Charles on 11 May 1804, departure up the Missouri is imminent.

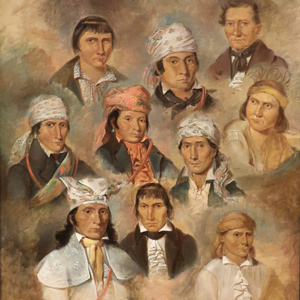

The Osages

by Joseph A. Mussulman, Kristopher K. Townsend

The Osage were experienced traders, exchanging horses and Indian slaves for French guns, knives, axes, kettles, and other metal objects. After the 1760s, the Osage adopted a new economic system of planting gardens in permanent villages, summer hunts in the plains, and fur-trapping in the winter.

The Kickapoos

Always on the move

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Perhaps more than any North American people, the Kickapoo exemplify the transitory nature of the native nations encountered during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In 1803, there was at least one village near Ste. Genevieve on the Mississippi River.

The Illinois Tribes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition set up camp near a town named after the Cahokia, one the Illinois tribes. The captains reported that Missourias, the Illinois, Cahokias, Kaskaskias, and Piorias were nearly destroyed by the Sauks and Foxes.

The Otoes and Missourias

by Kristopher K. Townsend

At the time of the expedition, the nation from which the Missouri River derived its name were so reduced by smallpox and attacks that they had abandoned their villages and merged with other tribes—Kansas, Osages, but primarily, the Otoes.

The Sauks and Foxes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

To outsiders in 1803, the Sauk and Fox people living on the Mississippi River in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin were seen as one people. Both peoples spoke the Sauk-Fox-Kickapoo dialect of Algonquian and had similar cultures and economies.

The Lenape Delawares

by Kristopher K. Townsend

About 1784, a small group of Shawnee and Delaware migrated from Illinois to southeastern Missouri. Ten years later, the Spanish encouraged members in Illinois to migrate the Cape Girardeau area as a way to protect their own settlements from the Osage.

The Potawatomis

by Kristopher K. Townsend

By 1800, the Potawatomi had successful traded with the French to the north and the Spanish in St. Louis. They resided in a large region surrounding the southern half of Lake Michigan between the Mississippi River and Lake Erie and extending south to the mouth of the Illinois River.

Synopsis Part 1

Washington City to Fort Mandan

by Harry W. Fritz

The Corps of Discovery, as it would be called, or the “corps of volunteers for North Western Discovery,” as Lewis put it, epitomized the rising glory of the United States—its sense of limitless possibilities and unparalleled opportunities.

Outfitting the Expedition

Buying supplies in Philadelphia and St. Louis

by Frank Muhly, Joseph A. Mussulman

The original shopping list contained more than 180 items, including various “Mathematical Instruments”, arms and accouterments, ammunition, clothing, camp equipage, provisions, Indian presents, medicine, and packing materials.

St. Louis

Gateway to the west

by Frances H. Stadler

In 1804 and in the presence of the Lewis and Clark expedition the little village, built and designed to be an outpost of the fur trade, shed its ambiguous Spanish-French parentage and took on full American citizenship.

The Mouth of the Missouri

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Missouri River still contributes its tint a few miles north of St. Louis. It is difficult to determine exactly how much, and how often, the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers changed during the nine decades after the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Wood River by Air

Starting point

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark recorded: “Capts. Lewis & Clark wintered at the enterance of a Small river opposite the Mouth of Missouri Called wood River, where they formed their party, Composed of robust Young Backwoodsmen of Character.”

Sugaring at River Dubois

Surrounded by maple trees at Camp Dubois, tapping and boiling the sweet, watery sap until it crystallized into sugar could begin as soon as the days warmed enough to get the sap rising in the trees.

Clark’s Military Rank

An elephant on the trail

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis had assured Clark that their situations would be identical in every respect, beginning with rank. The fact that Clark was actually a lieutenant was a secret kept throughout the expedition.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.