Seaman’s Creek was located, described, and named with Lewis’s spelling in Biddle’s edition of the journals, but was never subsequently applied on any maps of the area. That watercourse was named Monture Creek much later in the 19th century in memory of a Hudson’s Bay Company interpreter and trader, George Monteur, who was widely known as “one of the most trustworthy and highly regarded half-breeds in the Rocky Mountains.” He was killed in 1877 in a drunken brawl on the bank of the North Fork of the Blackfoot River, 8 miles east of “Seaman’s Creek,” and was buried where he died by some of his pioneer friends. The surname Monteur was a prominent one in the northwestern fur trade from the 1780s until the late 1800s[1]George Weisel, ed., Men and Trade on the Northwest Frontier as Shown by the Fort Owen Ledger (Missoula, Montana: Montana State University Press, 1955), 172-73. Donald Jackson, “Call him Good … Continue reading

Naming Seaman’s Creek

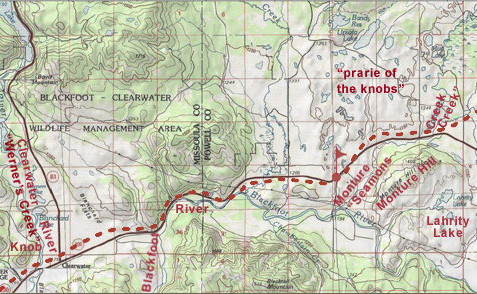

Twenty-eight and one-half miles upriver from their camp of 4 July 1806 the Indian road crossed a stream Lewis named after William Werner, who had started off as a troublemaker at the winter camp on River Dubois before the expedition officially began, but by this time had evidently redeemed himself in Lewis’s estimation. At least, Lewis’s gesture was something of a compliment, for the river passed through “an extensive and handsom plain” at Werner’s Creek.

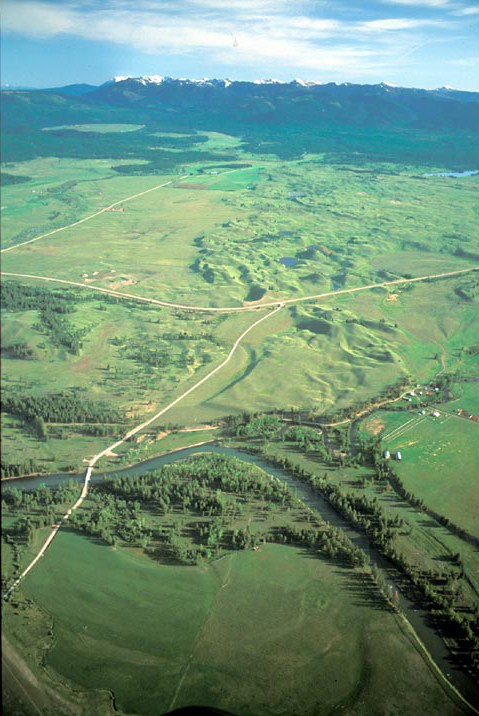

At mile 31, the end of that day’s travel, they camped near the mouth of a stream the captain named after his dog that, he wrote quite clearly in his courses and distances for the day, he called Seaman. The next morning they got going shortly after sunrise, which would have been around five a.m. They had entered the “extensive high prarie rendered very uneven by a vast number of little hillucks and sinkholes” that Lewis called “the prarie of the knobs.” Evidence on the ground indicated they were gaining on a large war-party of Atsinas from the northern plains, and were on guard against the likelihood of meeting them at any moment.

Seaman’s Unknown History

For a hundred years after Nicholas Biddle‘s paraphrase of the captains’ journals were published in 1814, nobody knew what kind of dog Lewis took along, nor what his name was, or whether he even had a name. Biddle may have known, but he didn’t say. He did, however, unintentionally foist a misunderstanding on the historiography of the expedition by bringing up the fact that a dog wandered into camp on 15 April 1805, which was thought to have been left behind by a band of Assiniboine Indians on the move. That settled the question for a hundred years, and artists happily included a common cur at Lewis’s side. Elliott Coues, in his 1893 commentary on Biddle’s edition, paused over “Seaman’s creek,” merely footnoting it as “a name I believe not found elsewhere in this History, and to the personality of which I have no clew,” and let it go at that. From then on, for quite a few years, the interpretation of Lewis’s simple statement of fact was befogged by the assumption that “Seaman” was some otherwise unknown person. Reuben Gold Thwaites, in his verbatim edition (1904) of the original journals, ignored the whole question. Whatever the dog’s name was, it didn’t appear to fit in the toponymic pattern established by the captains.

Seaman in the Journals

Late in the 19th century Newfoundland dogs were cross-bred with St. Bernards to counteract an epidemic of distemper among Newfies without compromising their temperament and power. Thus Newfoundland retrievers today are bulkier than those of Lewis’s time, but they are undoubtedly just as “sagacious” as Seaman was.[2]Louis Charbonneau, “Seaman’s Trail: Fact and Fiction,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 15, No. 4 (November 1989), 10. Incidentally, the preferred color for a Newfie at the beginning of the 19th century was parti-colored—black and white, or red and white.

Even after Lewis’s “Eastern journals” of 1803 and John Ordway‘s complete diary were discovered, and published in 1916,[3]Milo M. Quaife, ed., The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1926). He also read the dog’s name once as … Continue reading still nobody knew where or when Lewis got the dog, nor any details of his life up to the day (11 September 1803) Lewis found reason to remark that his companion was “of the newfoundland breed very active strong and docile.” On 16 November 1803, the day an Indian offered to buy him, Lewis added that his Newfy was a male and that he had paid $20 for him.[4]Twenty dollars was half of Lewis’s monthly salary as a captain in the Army. A few more details of his life on the trail were also added to the narrative. Overall, there were squirrels, geese, deer and antelope to retrieve. There were life-threatening beaver bites, stampeding bison, alarming noises in the night, needle-and-thread grass, prickly pear cactus, and one big scary moose. He shared the debilitating summer heat, bitter winter cold, and desperate hunger that the rest of the Corps endured.

The last time we hear of him in the journals is on 15 July 1806, the day before Lewis left White Bear Islands on his second exploration of the Marias River. The “musquetoes continue to infest us in such manner that we can scarcely exist,” he wrote, adding a sympathetic gesture of concern toward his canine companion: “my dog even howls with the torture he experiences from them.” Then, silence. It is commonly assumed that if he had not survived to the end of the expedition, there would have been a howl of grief from every man in the Corps. In this case, no news is the best news we could hope for. Their mascot’s longevity and ultimate fate remain subjects for thoughtful study (see Seaman’s Fate). He has also been the subject of numerous fictional treatments.[5]Lewis’s dog has been the inspiration for more than a dozen novels. One novelist’s discussion of the challenge is Louis Charbonneau’s, “Seaman’s Trail: Fact vs. … Continue reading

Seaman, Scannon, or Seamon?

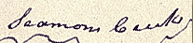

The name of Lewis’s dog as written by Clark on his map of Lewis’s route, 3-11 July 1806. Note the orthographic difference between the a and the o. Codex N, page 150, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

With the expedition’s known records now virtually complete, it was clear that Lewis’s sagacious[6]On several occasions Lewis’s dog was cited for his sagacity, which during the 18th century, according to Webster’s Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (New Haven, Conn.: … Continue reading companion is mentioned a total of 44 times—most often merely as “the dog,” “my dog,” “Lewis’s dog,” or even “our dog”—but only ten times by name. Quaife read it three different ways, as “Scannon,” “Scamon,” and “Semon,” always with the second syllable spelled “-mon.” The discussion stalled there for fifty years, with Scannon surfacing as the default pronunciation, as Ernest Osgood confirmed in 1976 in an essay entitled “Our Dog Scannon: Partner in Discovery.”[7]Ernest Osgood, “Our Dog Scannon: Partner in Discovery,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 26, no. 3 (July 1976), 8-17. Nine years later, Donald Jackson entered the fray with a decisive opinion titled “Call Him a Good Old Dog, But Don’t Call Him Scannon.” His name was “Seaman.” Lewis, concluded Jackson, “spelled it correctly when he gave the name to the creek.”[8]Jackson, ” . . . Good Old Dog,” 6. Lewis’s only mention of the name was the statement in his note to the final course on 5 July 1806: “3 m. to the entrance of a large creek 20 yds. wide Called Seaman’s Creek.” In 1993 Gary Moulton reaffirmed Jackson’s conclusion. Lewis’s orthography here, notes Moulton, “suggests the presently favored name for his dog.”[9]Moulton, 8:92n. Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1806, defined the noun “seaman” as “a mariner, sailor, animal, merman.” A … Continue reading

There is ample support for this conclusion. First of all, Lewis being the dog’s owner and master, he more than anyone else should know how to spell his pet’s name, and he was the only journalist who spelled it Seaman. Furthermore, the web-footed, lean, rangy ancestors of the bulky modern Newfoundland breed were famous as working dogs, bred and trained to help fishermen tend their nets, as well as to assist in the rescue of sailors in treacherous surf, or to pull heavily loaded sleds. The breed was a logical choice to accompany what was conceived as a a waterborne expedition, a voyage, across North America, and the name was a fitting testament to that premise: Sea-man, indeed! Coincidentally, the British poet George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), who was a younger contemporary of Lewis, acquired a Newfoundland retriever in the same year Lewis got his, and gave him the nautical name of Boatswain. A boatswain (pronounced bo’sən) is the petty (noncommissioned) naval officer in charge of a ship’s rigging and deck crew.[10]Mark Derr, A Dog’s History of America: How Our Best Friend Explored, Conquered, and Settled a Continent (New York: North Point Press, 2004), 121.

On the other hand, there remains another smidgen of evidence to the contrary that ought not to be overlooked. Every time Clark or Ordway wrote the dog’s name, the second syllable contained an o, not an a. Eight times, Seamon; once, Semon. Never did either end it with “-man,” “-men,” “-min,” or “-mun,” which casual, conversational pronunciation might have suggested phonetically. And they must have heard it often, for although some of the enlisted men may have had their own personal terms of affection for the captain’s dog, it would have been inappropriate to address him out loud with anything but his real name. And if we remember the predominance of phonetic spelling in their era, and their habituation to close listening, and if we ourselves listen to the sound of Seamon, with equal weight on both syllables, we hear the French name Simón.[11]Without a final e it is a man’s name, a form of the Biblical Hebrew name Shim’on, which means “listening.” Masculine or feminine, the French pronunciation is the … Continue reading

But if we place stress on the first syllable, and none on the second, the vowel in the latter becomes a schwa (ə), the most common vowel sound in English, which is formed in a mid-central oral position, without stress, and with unrounded lips. In that case, all of the vowels in the spellings referred to above would sound the same. Unfortunately, lacking any more hard facts to clarify this issue, we will never know whether the phonetic argument carries any weight or not. We’d best stick with “Seamən.”

Notes

| ↑1 | George Weisel, ed., Men and Trade on the Northwest Frontier as Shown by the Fort Owen Ledger (Missoula, Montana: Montana State University Press, 1955), 172-73. Donald Jackson, “Call him Good Old Dog, but Don’t Call him Scannon,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 11, No. 3 (August 1985), 4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Louis Charbonneau, “Seaman’s Trail: Fact and Fiction,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 15, No. 4 (November 1989), 10. |

| ↑3 | Milo M. Quaife, ed., The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1926). He also read the dog’s name once as “Shannon” (4 July 1804), but may have been been thinking of Private George Shannon, which would have been a gross misinterpretation, considering the circumstances. |

| ↑4 | Twenty dollars was half of Lewis’s monthly salary as a captain in the Army. |

| ↑5 | Lewis’s dog has been the inspiration for more than a dozen novels. One novelist’s discussion of the challenge is Louis Charbonneau’s, “Seaman’s Trail: Fact vs. Fiction,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 15, No. 4 (November 1989), 8-12. Two books about dogs’ roles in history may also be recommended: Mark Derr, A Dog’s History of America: How Our Best Friend Explored, Conquered, and Settled a Continent (New York: North Point Press, 2004); Stanley Coren and Andy Bartlett, The Pawprints of History: Dogs and the Course of Human Events (New York: Free Press, 2002). |

| ↑6 | On several occasions Lewis’s dog was cited for his sagacity, which during the 18th century, according to Webster’s Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (New Haven, Conn.: Sidney’s Press, 1806), meant “quick of scent or thought, acute.” The noun was used in that sense in European treatises on quadrapeds such as coyotes and wolves, or any other animal that displayed “intelligence.” |

| ↑7 | Ernest Osgood, “Our Dog Scannon: Partner in Discovery,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 26, no. 3 (July 1976), 8-17. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, ” . . . Good Old Dog,” 6. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, 8:92n. Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1806, defined the noun “seaman” as “a mariner, sailor, animal, merman.” A “merman” was the male counterpart of the mythical “mermaid,” often depicted as half fish and half man, wearing a crown and holding a conch shell. Whether or not Lewis was aware of all these meanings of the name is only conjectural. |

| ↑10 | Mark Derr, A Dog’s History of America: How Our Best Friend Explored, Conquered, and Settled a Continent (New York: North Point Press, 2004), 121. |

| ↑11 | Without a final e it is a man’s name, a form of the Biblical Hebrew name Shim’on, which means “listening.” Masculine or feminine, the French pronunciation is the same—”see-moan.” |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.