Lander’s Fork

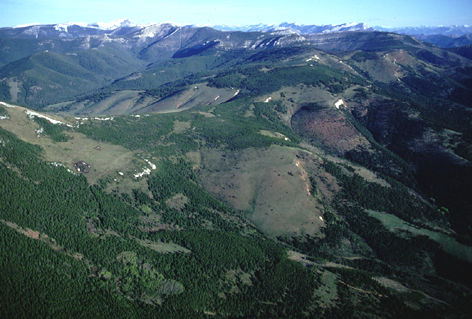

In the middle background are the scars of two large forest fires that were started by lightning in 2000.

The Indian road led up the east side of the “main creek,” which in 1854 was named for F. W. Lander, who was the next white person to explore it. Lander was a civil engineer with the Railroad Survey expedition of 1853-55 that was commissioned by Congress and commanded by Isaac I. Stevens.[1]Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound, by Isaac I. Stevens, … Continue reading

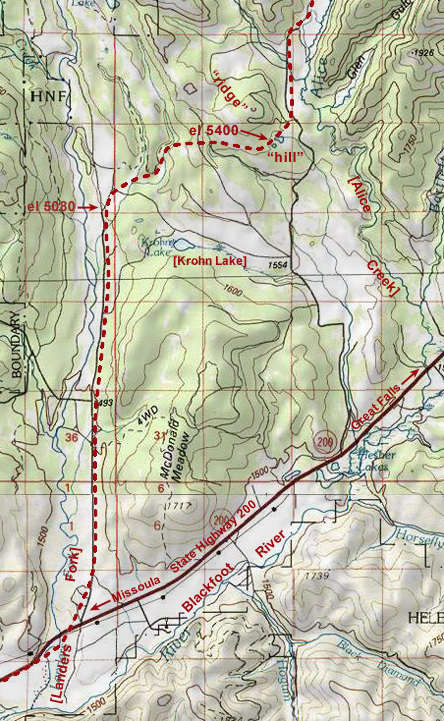

Lewis considered this stream to be the mainstem of Cokhalah ishkit, partly because the main Indian road ran through its valley, but perhaps also because it was clearly a larger watercourse than what was left of the Big Blackfoot River beyond its confluence with Landers Fork. At that junction, it is approximately 30 miles to the sources of Landers Fork, but only about 16 miles to the head of the Blackfoot River.

Patrick Gass has told us more details about the route up Landers Fork toward the Continental Divide. On the cloudy morning of 7 July 1806, following a rainy night, the party continued up the valley, “which is very beautiful, with a great deal of clover in its plains.”

Having gone about five miles, we crossed the main branch of the river, which comes in from the north; and up which the road goes about five miles further and then takes over a hill towards the east. On the top of this hill there are two beautiful ponds, of about three acres in size. We passed over the ridge and struck a small stream, which we at first thought was of the head waters of the Missouri, but found it was not. Here we halted for dinner.

It has been suggested that today’s Krohn Lake might have been one of the “ponds” Gass referred to. However, that lake may have been 15-20 acres in size, and probably would not have been visible from their route anyway. The Indian road most likely led them close to the two unnamed ponds on the “hill” or “ridge,” which together might have equalled three acres. Today they are just marshy swales.

Alice Creek

They rode up the right side “main stream”—Landers Fork—and up the left side of Alice Creek, which is pictured above. The narrow bottoms were “covered with low willow and grass.” It still looks very much the way it would have 200 years ago. To stay out of the willows and the beaver ponds, the Indian road probably wound among the trees where the logging road makes its way today. Lewis and his party observed “much appearance of beaver” and “many dams.” They stopped for their midday meal at a large beaver dam.

Beaver populations throughout North America were greatly reduced during the 18th and early 19th centuries, especially following the Corps of Discovery’s quest for them. But despite ecologists’ dire warnings about the accelerating extinction of wild creatures, beaver have shown a remarkable and widespread recovery, which has been accompanied by a fuller human appreciation of Castor canadensis as a keystone species upon which many others depend for survival.

Beaver trapping is still carried on throughout the U.S., especially in the northern latitudes. In Montana a license for trapping is required by the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, but inasmuch as the beaver population currently is quite large, overall, and with comparatively few trappers active at the present time, there are no limits on beaver taken during the open season, 1 November through 15 April.

In general, fur trapping is a contentious issue that is fought aggressively by animal protection groups. In particular, the trapping of beaver is still deplored by many Indian people, who have traditionally regarded beaver as semi-sacred creatures on account of their extraordinary skills as “ecosystem engineers.”[2]See Peter Moyle and Mary A. Orland, Essays on Wildlife Conservation, Chapter 2, “A History of Wildlife in North America,” http://marinebio.org/Oceans/Conservation/Moyle/ch2.asp. Accessed … Continue reading In many parts of the country, however, trapping is widely employed to control the impacts of over-population by these opportunistic rodents, especially in urban and suburban settings, on valuable agricultural land, and wherever intensive land management is practiced. Farmers and ranchers in central and eastern Montana, for example, must keep beavers from damming irrigation ditches or digging dens in the banks, and can request special damage-control trapping permits at any time of the year.

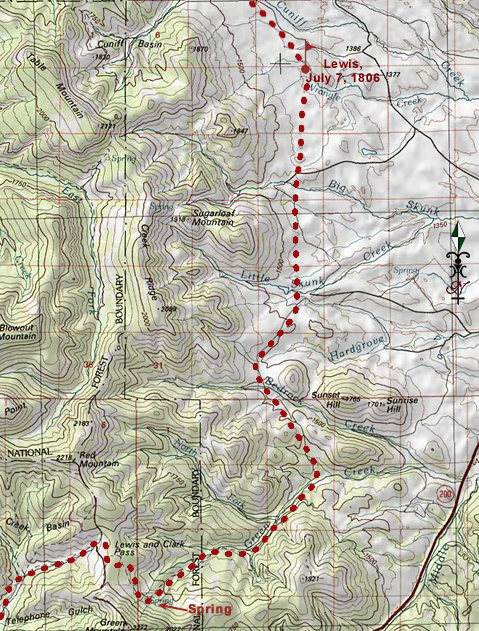

The Great Divide

Sergeant Gass recorded that on the 7 July 1806, Lewis’s detachment took a three-hour lunch break—their word was “dinner”—somewhere on Alice Creek, then proceeded four more miles up that drainage, “when we came to the dividing ridge between the waters of the Missouri and Columbia.” They “passed over the ridge and came to a fine spring the waters of which run into the Missouri.” After another mile or so, according to Gass, they “turned a north course along the side of the dividing ridge for eight miles, passing a number of small streams or branches.” Even with time out for a long lunch, they covered an estimated 32 miles before settling in for the night at 9:00 p.m.

Lewis claimed that from the gap on the dividing ridge he could see “fort mountain”—Square Butte—to the northeast, “distant about 20 miles.” It may be among the indistinct heights on the hazy horizon at the photo’s left margin, but it is actually almost twice that far from the pass. Once again, the normally dry atmosphere of the northern plains had led him to underestimate distances.

Lewis’s route from so-called Lewis and Clark Pass (even though Clark never was here) to the Sun (“Medicine”) River and down to the Great Falls of the Missouri is perhaps one of the least known and, because much of it crosses private property, the least-often retraced in the entire itinerary of the Corps of Discovery. This view looks northwest into the heart of the Northern Rockies, where the higher peaks average eight to nine thousand feet MSL.

Rocky Mountain Front

Against a backdrop of snow-crowned, nine- to ten-thousand-foot peaks along the Continental Divide, this May-morning view of the Rocky Mountain Front in 2004 possibly appears much like it would have looked in late May or early June 200 years ago, given the fact that at this latitude spring begins about two weeks earlier now than it did then.

Lewis’s trip down from the “gap” and then north along the foot of the mountains was comparatively uneventful. He and his men were expecting to encounter bison at any moment, but saw nothing more than “much old appearance of dung, tracks &c.” After they pitched camp on a “small run under the foot of the mountain”—possibly Wrangle Creek—”Drewyer killed two beaver and shot third which bit his knee very badly and escaped.”

Lewis’s Route

Alice Creek Historic District is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The trail to the summit is managed by the Helena National Forest.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound, by Isaac I. Stevens, Governor of Washington Territory. 1855. Volume 12, Book 1, 33. Lewis did not take time to make the observations necessary for calculating either latitude or longitude, but the Railroad Survey determined it to be 47°08’N and 112°24’W. The elevation is 6426 feet above mean sea level. Lewis could not have measured the elevation because portable barometers were not yet available when his expedition was outfitted, in 1803. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Peter Moyle and Mary A. Orland, Essays on Wildlife Conservation, Chapter 2, “A History of Wildlife in North America,” http://marinebio.org/Oceans/Conservation/Moyle/ch2.asp. Accessed 30 March 2005. Alexander Henry the elder (1739-1824) reported: “Beavers, say the Indians, were formerly a people endowed with speech, not less than with the other noble faculties they possess; but, the Great Spirit has taken this away from them, lest they should grow superior in understanding to mankind.” Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories between the years 1760 and 1776 (New York: I. Riley, 1809), 130-31. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.