They described the Milk River as “possessing a peculiar whiteness, being about the colour of a cup of tea with the admixture of milk.”

Loney always wondered how that river knew

where to bend, why it wandered with such

feckless purpose. He wondered if it always

sought the lowest ground, or was his mind

such a shambles that he assumed there was

a reason behind its constant shifting?

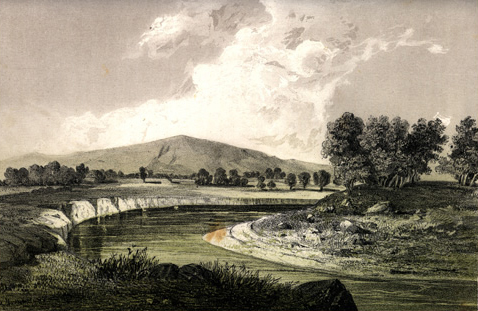

Millions of years ago the valley of the river Lewis and Clark named Milk was part of the main channel of the Missouri. In this photo, taken a month or so later than the one below, it writhes through its ancient bed, a pitiful trickle of its original self, still contributing its rich murk to “The Big Muddy.”

Creeping down the nearly imperceptible slope of the northern high plains, this is the stream Lewis and Clark described as possessing a peculiar whiteness, being about the colour of a cup of tea with the admixture of a tablespoonfull of milk. Every turn furthers its languorous descent to mingle with the Missouri River. In the six straight-line statute miles from the upper left to the lower right corner of the image, the river meanders for 26.5 miles toward all points of the compass, falling only five feet, inch by merest inch.

The Hidatsa Indians had told the captains to watch for it. “About one hundred fifty miles on a direct line, a little to the N. of West [from the mouth of the Yellowstone], a river falls in on the N. side called by the Minetares [Hidatsas] Ah-mâh-tâh, ru-shush-sher or the river which scolds at all others.”[2]Unfortunately, neither the Hidatsas nor the captains left any clues as to the reason behind that enigmatic name. The copyist who first edited Joseph Whitehouse‘s journal, inserting his personal … Continue reading

This river they state to be of considerable size, and from it’s position and the direction which they give it, we believe it to be the channel through which those small streams on the E side of the Rocky Mountain, laid down by Mr. Fidler[3]Peter Fidler (1769–1822) was a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company who copied a sketch-map given him by a Blackfeet Indian informant named Ackomokki. It was pure hearsay in its … Continue reading, pas to the Missouri. It takes it’s source in the Rocky mountains S. of the waters of the Askow or bad river, and passes through a broken country in which there is a mixture of woodlands and praries.

They arrived at its mouth on May 8, 1805, and stopped “in a handsome bottom” for lunch:

I took the advantage of this leasure moment and examined the river about 3 miles; I found it generally 150 yards wide, and in some places 200. it is deep, gentle in it’s courant, and affords a large boddy of water; it’s banks, which are formed of a dark rich loam and blue clay, are abbrupt and about 12 feet high. it’s bed is principally mud. I have no doubt but it is navigable for boats perogues and canoes, for the latter probably a great distance. the bottoms of this stream are wide, level, fertile and possess a considerable proportion of timber, principally Cottonwood. from the quantity of water furnised by this river it must water a large extent of country; perhaps this river also might furnish a practicable and advantageous communication with the Saskashiwan river; it is sufficiently large to justify a belief that it might reach to that river if it’s direction be such.

Unusual Color

The confluence of the Milk River (left) and the Missouri, looking downstream (eastward). Note the parallel rows of cottonwood trees marking the various historic margins of spring freshets. At right are fringes of the Milk River Hills.

Lewis was particularly impressed by the color of this stream the Hidatsas explained was the principal northern source of the Missouri. “The water of this river,” he wrote, “possesses a peculiar whiteness, being about the colour of a cup of tea with the admixture of a tablespoonfull of milk.” Clark concurred: “It precisely resembles tea with a considerable mixture of milk.” From the color of its water, Lewis concluded, “we called it Milk river.” Patrick Gass, with different eyes, or imperfect recollection, remarked that “there is a good deal of water in this river which is clear.” We may suppose that it was not as milky as it appears in Jim Wark’s photo, above, which may reflect a recent, heavy rain. In any case, the reason for its hue is that it drains a broad valley containing weathered, silty glacial till and shale, as well as sand, and passes through a layer of white clay within its middle reaches.

Returning downriver, Lewis paused for a few minutes at the mouth of the Milk again on 4 August 1806. “This stream is full at present, and its water is much the color of that of the Missouri. It affords as much water at present as Maria’s river, and I have no doubt extends itself to a considerable distance North.” Gass, too, noted that it “was very high and the current strong.”

Meanders and Courses

Needless to say, Lewis, having recently been disappointed to discover the Marias didn’t satisfy his objectives, was still hoping that the Milk River drainage would define the northern boundary of Louisiana Territory near the South Saskatchewan River, or at least a little north of the 50th parallel. He would have been disappointed, for its northern tributaries begin at no more than about 49° 14′ North Latitude.

They looked it over carefully, as far as they could see. Clark climbed to “a very high point opposite to the mouth of this river”—probably today’s Deadman Butte, in the Milk River Hills. Lewis learned from him that he had enjoyed “a perfect view of this river and the country through which it passed for a great distance. . . . Capt C. could not be certain but thought he saw the smoke [from] some Indian lodges at a considrable distance up Milk river.” Lewis stiffened, groped for a respectful euphemism, and settled on the one he used for grizzly bears and wolves. “We do not wish to see those gentlemen just now as we presume they would most probably be the Assinniboins and might be troublesome to us.”

The Milk River begins 732 miles (1,178.5 km) west of its confluence with the Missouri, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountain Front, on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation near Glacier National Park.[4]River Mile Index of the Missouri River (Water Resources Division, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, 1979), p. 29. Since 1921, with the help of human engineering, it has drawn part of its water from the park’s large Lake Sherbourne, which nature originally designed to empty into Hudson’s Bay via the Belly River. The objective was to provide a backup source of water to supply the elaborate irrigation system during dry late summer months.[5]The Milk River Project of the U.S Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, was initiated in 1902, followed by forty-two years of development. A detailed description and history of the … Continue reading The Milk flows northeast across the International Boundary south of Lethbridge, Alberta, and returns to Montana 200 miles downstream, northwest of Havre (HAVE-er). A short distance upstream from Havre, Fresno Dam impounds a reservoir from which irrigation water is distributed to 120,000 acres of alfalfa, wheat, barley, and other crops along the Lower Milk River.

Creeping down the nearly imperceptible slope of the northern high plains, every turn furthers its langourous descent to mingle with the Missouri River. In the six straight-line statute miles from the upper left to the lower right corner of the image, the river meanders for 26.5 miles toward all points of the compass, falling only five feet, inch by merest inch.

Stevens’ Survey

Desolate? Forbidding? There was never a country that in its good moments was more beautiful. Even in drouth or dust storm or blizzard it is the reverse of monotonous, once you have submitted to it with all the senses. You don’t get out of the wind, but learn to lean and squint against it. You don’t escape sky and sun, but wear them in your eyeballs and on your back. You become acutely aware of yourself. The world is very large, the sky even larger, and you are very small. But also the world is flat, empty, nearly abstract, and in its flatness, you are a challenging upright thing, as sudden as an exclamation mark, as enigmatic as a question mark.

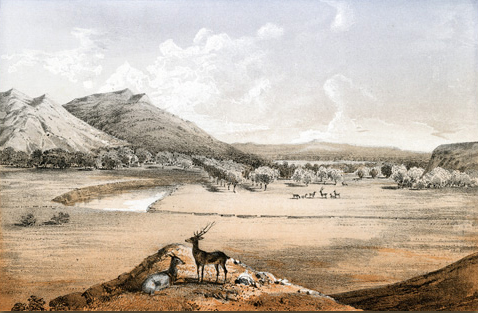

Milk River near junction of Missouri

by John Mix Stanley (1814–1872)

Stevens, Railroad Survey, 1803. Lithograph, 8.25 by 8.875 inches.

From 1853 until 1855, Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862), who recently had been named Governor of the new Washington Territory, led a government-sponsored overland expedition to find the best route for a railroad across the northwestern United States from Minnesota to Puget Sound, between 47° and 49° North Latitude. The objective was much like that of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of fifty years earlier, except that this one was inspired by the new technology that had already begun to transform the new mode of mass transportation across the continent. Also like the first expedition, the ultimate goal was to control commerce between the eastern and western boundaries of the Pacific Ocean.

Leaving Minneapolis, Minnesota, in June 1853, he arrived in what is now northeastern Montana in mid-August. Stevens’s report for the eighteenth of that month read:

Encamped on the Milk river, 16 miles being the day’s march. Here we determined to remain a day to prepare charcoal for the blacksmith, and to make observations for the geographical position of its mouth, which is considered a very important point in the survey. Our camp was surrounded by a large grove of cottonwood,and near it was a delightful spring of water. The valley of Milk river is wide and open, with a very heavy growth of cottonwood as far as the eye can reach, which is also to be found along the adjacent shores of the Missouri.[7]Isaac I. Stevens, Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 vols. (Washington, D.C., … Continue reading

With characteristic enthusiasm he observed that “the prairie country is not only well grassed, but much of it arable. This is emphatically the case with the bottoms of the Missouri, which our route followed.”

The American portraitist, artist and illustrator John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), served as one of the official artists with the Stevens railroad survey party to the Northwest. His record of highlights along the route often combined documentary verisimilitude with romantic fantasy, as in the focal point of this scene–a quadruped resembling an elk-caribou[8]It is possible that a subspecies of the elk-like caribou, Rangifer tarandus, —may once have ranged as far south as the Milk River, but Lewis and Clark never mentioned seeing any. A small endangered … Continue reading cross stands near a reclining pronghorn, the first animal too small, the other too large.

The rows of trees in the middle of Stanley’s drawing, which resemble an orchard, are supposed to be cottonwoods, and are only slightly “interpreted” in that they appear equidistant from one another in straight rows. Real cottonwood trees germinate within a few feet of the high-water mark on riverbanks, and consequently grow in parallel rows that trace the contours of successive high-water marks.

Panther Mountain

If William Clark had been a prophet as well as an explorer, and a student of human watersheds as well as a geographer, he might have made some interesting speculations as he stood on the Milk River bluffs looking northward toward the region which would retain longer than any part of the United States, and any but the sub-arctic parts of Canada, the characteristics of the West that he knew in 1805.

Stevens’s report continued:

This morning was clear, cool, pleasant. . . . Engineer parties, both yesterday and to-day, have been actively at work getting in the country bordering the route of the main party. The road, as usual, was excellent to-day. I despatched a small party across Milk river to Panther[10]The panther, Felis concolor, also called mountain lion, puma, catamount, or cougar, was not unfamiliar to the Corps, but Lewis described it briefly in his journal entry for 27 February 1806. … Continue reading Hill . . . to observe the country. Game was very abundant; plenty of buffalo, antelope, and beaver.[11]Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1855-60), vol. … Continue reading

Stanley’s perspective looks down the Milk River and across the Missouri toward the Milk River Hills. There is no land form among them today that is known as “Panther Mountain.” It is possible that the eminence on the horizon is the one now called Deadman Butte. Nearly five decades earlier, Meriwether Lewis had written, on the morning of 8 May 1805: “Capt Clark who walked this morning on the Lard. shore ascended a very high point opposite to the mouth of this river; he informed me that he had a perfect view of this river and the country through which it passed for a great distance.” Probably 50 or 60 miles, Nicholas Biddle added after discussing the point with Clark in 1810. According to Moulton (Journals, 4:124) it may have been Elliott Coues, about 1890, who penciled the next words into the original journal entry: “To see 60 miles would require a height of 1000 feet.”

If Clark could have climbed to a point 1,000 feet above the river, the northern horizon would have been slightly more than 42.6 miles away. But the highest point opposite the likely place where the Milk flowed into the Missouri in those days is nearly 2,700 feet above Mean Sea Level, and the MSL elevation of the confluence was approximately 2,020 feet. From only 680 feet above river level, the farthest horizon from Clark—and from Stevens’s “small party” too—would have been only ± 35 straight-line statute miles northward, roughly the equivalent of two days’ travel.

Some two weeks later Lewis realized that they were under the influence of an atmospheric illusion. “The air so so pure in this open country,” he wrote, “that mountains and other elivated objets appear much nearer than they real are” (24 May 1805). The simple fact behind the phenomenon is that the humidity in that part of the plains was consistently much lower than they had been accustomed to, and therefore more transparent.

Near the Bears Paw

The drama of this landscape is in the sky, pouring with light and always moving. The earth is passive. And yet the beauty I am struck by . . . is a fusion: this sky would not be so spectacular without this earth to change and glow and darken under it. And whatever the sky may do, however the earth is shaken or darkened, the Euclidean perfection abides. The very scale, the hugeness of simple forms, emphasizes stability. . . . Eternity is a peneplain.

As the Corps of Discovery approached and passed the mouth of the Yellowstone River, Lewis and Clark almost daily expressed their delight with the land and the scenery. They saw what any plantation-owner from the Piedmont of Virginia would wish to see—”rich black earth . . . dark, rich, mellow-looking loam.” Pleasant, extensive, level, fertile plains, “beautiful in the extreme.” On 19 May 1805, they passed the mouth of the Musselshell and shortly entered what Clark, a week later, would call “the Deserts of America.”[13]26 May 1805 was the day Lewis thought he “beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time.” He was mistaken; what he saw probably was the Highwood Mountains near Great Falls. That was also … Continue reading But Lewis didn’t revise his earlier impressions of the high plains, which could well have served as advertisements for Jim Hill’s railroad, which was to transect this region in the 1890s.

Lewis clung wholeheartedly to the sort of optimism that thereafter would distort the otherwise good judgment of countless explorers, and with which land speculators, encouraged by railroad builders, would in turn infect thousands of hopeful farmers and ranchers around the turn of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, many of them were ill-prepared to cope with this land on its own terms.

On 30 August 1853, forty-eight years after the Corps of Discovery passed through, explorer Isaac Stevens sent three of his men, including artist John Mix Stanley, to climb the the highest peak in the Bears Paw range and from there study the surrounding country, especially westward toward the Rocky Mountains. Their report was gladsome, and Stevens was enthusiastic.

At the upper portion of Milk river, for some thirty miles, the water appeared only in pools, but it was exceedingly cool, delightful, and pure, and was evidently running water. There is a singular fact connected with all the streams of this country, which become dried up in the summer and fall, that as soon as the cold weather comes on the water rises in the streams, and the usual quantity passes down. The fact is, the streams do not dry up; only in the summer and early fall their course is in the sands, and by sinking wells the purest and clearest water would be found at a depth of from two to three feet; and I have no doubt, from my own personal observation, that ample supplies of water would, in the driest season, be afforded by Milk river for the largest emigration, or for the largest business of a double track railroad.[14]Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 Vols. (Washington, D.C., 1860), vol. 12, … Continue reading

—Isaac Stevens

The Milk River Confluence is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Properties surrounding the confluence are owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, and private owners.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | New York: Harper & Row (1979), p. 113. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Unfortunately, neither the Hidatsas nor the captains left any clues as to the reason behind that enigmatic name. The copyist who first edited Joseph Whitehouse‘s journal, inserting his personal guesswork, transcribed it as “Scalding Milk River.” |

| ↑3 | Peter Fidler (1769–1822) was a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company who copied a sketch-map given him by a Blackfeet Indian informant named Ackomokki. It was pure hearsay in its representation of the Northern Rockies and their drainages, since Fidler himself did not travel south of the fiftieth parallel until he visited the Knife River villages in 1813, Aaron Arrowsmith,however, whose state-of-the-art map Lewis and Clark carried, relied upon it heavily. See John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), pp. 244–45. |

| ↑4 | River Mile Index of the Missouri River (Water Resources Division, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, 1979), p. 29. |

| ↑5 | The Milk River Project of the U.S Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, was initiated in 1902, followed by forty-two years of development. A detailed description and history of the project is available at http://www.usbr.gov/WaterSMART/bsp/docs/finalreport/Milk-StMary/Milk-StMary_SummaryReport.pdf ( Accessed 28 January 2008). |

| ↑6 | Wallace Stegner, “The Question Mark in the Circle,” from Wolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier (New York: Viking Press, 1955), 8. |

| ↑7 | Isaac I. Stevens, Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1860), vol. 12, bk I, Narrative and Final Report, 90, Plate 18. |

| ↑8 | It is possible that a subspecies of the elk-like caribou, Rangifer tarandus, —may once have ranged as far south as the Milk River, but Lewis and Clark never mentioned seeing any. A small endangered herd of woodland caribou, the subspecies R. t. caribou, survives today in the mountains of northern Idaho and northwestern Montana. Domesticated caribou are commonly called reindeer. |

| ↑9 | Wallace Stegner, “First Look,” from Wolf Willow: a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier (New York: Viking Press, 1955). |

| ↑10 | The panther, Felis concolor, also called mountain lion, puma, catamount, or cougar, was not unfamiliar to the Corps, but Lewis described it briefly in his journal entry for 27 February 1806. Whitehouse, in his journal for 23 June 1803, spelled the word “painter,” reflecting a regional pronunciation of panther possibly influenced by the French form, panthère. |

| ↑11 | Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1855-60), vol. 12, bk. 1, bk I, Narrative and Final Report, 91, Plate 20. |

| ↑12 | Wallace Stegner, “The Question Mark in the Circle,” from Wolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier (New York: Viking Press, 1955), 7. |

| ↑13 | 26 May 1805 was the day Lewis thought he “beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time.” He was mistaken; what he saw probably was the Highwood Mountains near Great Falls. That was also the day when he took time to enter into his journal Toussaint Charbonneau‘s recipe for his delectable “white pudding” boudin blanc. |

| ↑14 | Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 12 Vols. (Washington, D.C., 1860), vol. 12, bk 1, Narrative and Final Report, p. 90, plate 22. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.