Around Point Ellice

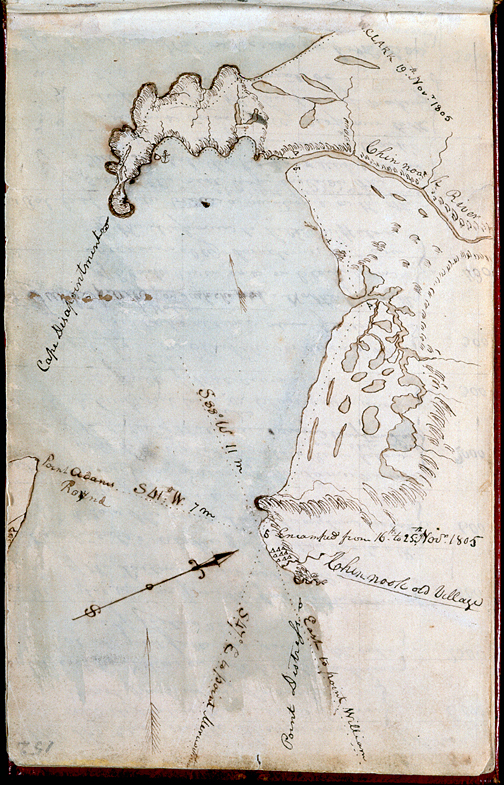

Although this map is labled “ca. November 16-25” in Moulton (6:52), Clark probably drew it sometime during the winter of 1806 from the field notes he made in November (see Moulton, Atlas, Maps 90-93). For one thing, the almost incessant rain and wind they endured from the time they left Station Camp until the captains moved into their quarters at Fort Clatsop on 23 December 1805 would have prevented Clark from preparing such a detailed chart. Moreover, “Point William” (today, Tongue Point) did not acquire that name until 27 November 1805 (Moulton, 6:90). His “Point Lewis” is now Smith Point, at the west end of Astoria, Oregon, and slightly east of the mouth of Youngs Bay. “Point Distress” is now Point Ellice, Washington. The distance from Station Camp to Cape Disappointment would actually have been 6.9 miles, not 11; his 7-mile estimate of the distance to Point Adams would have been more accurately 3.8 miles.

—Robert N. Bergantino in Station Camp Observations.

On 15 November 1805, a break in the weather permitted the party to paddle its canoes around Point Ellice to a sandy beach between the point and Cape Disappointment, where they were to spend the next ten days. Captain Clark concluded:

this I could plainly See would be the extent of our journey by water, as the waves were too high at any Stage for our Canoes to proceed any further down.

Sergeant Gass put it in a different light:

We are now at the end of our voyage, which has been completely accomplished according to the intention of the expedition, the object of which was to discover a passage by the way of the Missouri and Columbia rivers to the Pacific ocean; notwithstanding the difficulties, privations and dangers, which we had to encounter, endure and surmount.

At any rate, the Corps remained here for ten days while exploring the coast a little to the north, looking for the white traders that Indians had told them lived thereabouts, and hoping to find a more suitable winter campsite than the exposed location that circumstances had forced them to choose temporarily.

On two occasions Clark referred to their bivouac as “Station Camp”, since he had triangulated its location with reference to prominent landmarks visible from there, making of it a surveyor’s “station” (see also Clark’s Lookout.

Lewis and Clark named the bay Haley’s after the Indians’ favorite trader, the beneficent Captain Samuel Hill—the last name having gained a syllable as it passed over Chinookan tongues—of Boston. Hill had anchored in the bay the previous April, and would return within a few weeks after the Corps started home the following March. Today, however, we know the bay by the name Lieutenant William Broughton, exploring the river on George Vancouver’s orders in 1792, wrote on his map; Broughton found anchored here a ship commanded by a Captain James Baker.

How Long is a River?

Lewis and Clark carried some instruments for calculating distances–a chronometer, or clock, a surveyor’s compass, and an instrument for determining latitude and longitude. Odometers or “trip meters” were unknown to them. Instead, as experienced frontier soldiers and frontiersmen they had a strong sense of pace, time, and distance that is impossible for most modern civilian travelers to replicate, much less appreciate. So, how far did they travel, really?

When Clark arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River on 16 November 1805, he calculated that he had covered 4,142 miles from the mouth of the Missouri River. The National Park Service, which oversees the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, states that it is actually about 3,700 miles long. A leading student of the expedition has calculated that Clark’s estimate was about 15 percent longer than actual. Why the discrepancies?

Over-estimation

This chainsaw sculpture of Lewis and Clark was created by Fred Bero, of Ilwaco, Washington. For many years, it was located at the site of “Station Camp,” two miles west of the Washington end of the Astoria-Megler Bridge. It stood in the town of Long Beach until the mid-1990s, when it was replaced with a bronze sculpture by Stanley Wanlass.

Representing a blend of Euro-american and Indian styles, it serves as a reminder that over the past 200 years the story of the expedition has been preserved not just by scholars but also by local artists and storytellers. However, wood decays quickly in the moist coastal climate, so many people felt that the story in general, and this site in particular, deserved a more permanent memorial.

One answer is that while traveling on water, or when afoot in rough terrain such as the Bitterroot Mountains, Clark tended to overestimate distances by as much as one-third. Only when he was on horseback were his mileage figures more accurate. Nevertheless, his feat of measuring more than half a continent was an almost Herculean task, and one can’t imagine anyone doing as well today, given the same circumstances.

But what would the final “correct” figure mean, after all? In general, measured distance and felt distance can be miles apart, according to the character of the water, land or air covered, the means of travel, the weather, the time available, and even the health and attitude of the traveler. We’ve all experienced this to one extent or another. According to the latest Rand-McNally road atlas, it’s exactly 2,151 real miles from St. Louis to Fort Clatsop via state and interstate highways. By jet plane, nonstop to Portland, then by commuter plane to Astoria, it’s only 1,800 air miles. But given an unforseen delay, combined with some personal reason for urgency, the felt distance takes on a new dimension.

Ever-changing Rivers

There’s another factor that prevents us from saying how far the expedition “really” travelled, and that is that rivers are, by their nature, dynamic. Their lengths change from season to season, and from year to year. Left untrammeled by levees, dikes, or dams, they are continually bending and straightening, coiling and uncoiling, never pausing for our rulers, never posing for their portraits.

For example, in 1805 Clark figured the distance from the mouth of the Missouri to the mouth of the Knife River, near Fort Mandan, at 1616 miles. In 1890 the U.S. Corps of Engineers calculated it was then just 1514 miles between the same two points. In 1941, measured along the thalweg, or deepest part of the riverbed, the distance appeared to be 1441 miles. In 1960, with only two dams in place, it was 1376 miles. Yet nearby St. Louis, Missouri and nearby Bismarck, North Dakota haven’t moved an inch.

To look at it another way, if the Lewis and Clark expedition could be repeated today under precisely the same travel conditions, including the same equipment and corresponding delays enroute, it would take 22 days less than it took them in 1804.

Middle Village-Station Camp is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site provides interpretation and is part of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks.—ed.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.