Fatigued and physically sick after crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, the expedition is aided by the Nez Perce. With their help, they find a location on the Clearwater River to build five dugout canoes and employ the Nez Perce method of burning out the Ponderosa pine logs.

The Nez Perce agree to take care of the expedition’s horses while they continue to the Pacific Ocean. Two Nez Perce chiefs volunteer to guide them down the Clearwater and Snake to the Columbia. The guides help scout the rapids and introduce the expedition to the various Nez Perce and Palouse bands fishing in the many rapids.

On 16 October 1805, they negotiate the last Snake River rapid and arrive at the Columbia River where many Yakamas and Wanapums are gathered. About two hundred men approach, singing and beating their drums.

The Palouses

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Palouses had coalesced around four primary villages on the lower Snake River: Penewawa, Almota, Wawaiwai, and Palus. Lewis and Clark estimated their population as 2,300 which included Northern Nez Perce.

The Wanapums

Lewis and Clark called them “Sokulks” but they were ‘river people’ from the Sahaptin wána (river) and pam (people). Wanapam is an alternate spelling.

The Yakamas

The Yakama’s first Euro-American contact was the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. The captains named the people Chim’-nah-pum’ which was the name of the village at the mouth of the Yakima River.

The Umatillas

After emerging from the Wallula Gap on 19 October 1805, Clark came across some Umatillas hiding in their lodges, and he committed a serious faux pas by entering without permission.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Walla Wallas

Walla Wallas, sometimes Waluulapam and sometimes on this site as Walula, are a Sahaptin-speaking indigenous people that lived primarily along their namesake river. There has been disagreement among historians regarding the nation’s etymology.

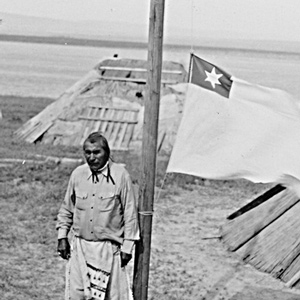

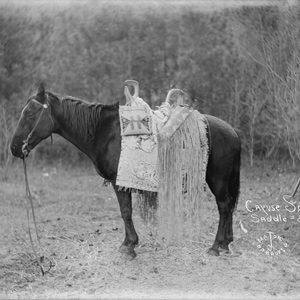

The Cayuses

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Clark’s name for the Cayuse, the Ye-E-al-po Nation, may have been his phonetic spelling of the Nez Perce name for them—Waiilatpu. The people are noted for their namesake horses and the 1847 murders at the Whitman Mission.

Through Nez Perce Eyes

An interview with an elder

by W. Otis Halfmoon

We call ourselves Ni-mee-poo, which means “The People.” We also call ourselves Tsoopnitpeloo, and Tsoopnitpeloo means “The Walking-Out People”—people from the mountains come to the plains, to hunt buffalo.

Synopsis Part 4

Lemhi Valley to Fort Clatsop

by Harry W. Fritz

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

Weippe Prairie Villages

Nez Perce camas grounds

by Joseph A. Mussulman

For countless generations, Weippe Prairie (prounouced WEE-yipe), like Travelers’ Rest, was a major node in the transportation, trade, and social networks of the Rocky Mountain West.

The Clearwater River

Looking for a canoe camp

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark spent the night of 21 September 1805 at Twisted Hair’s camp on an island in the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River. The next morning the chief and his son accompanied him back up to the village on Weippe Prairie where he expected to rendezvous with Lewis.

The Clearwater Canoe Camp

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Still sick and exhausted from their recent crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains, Lewis, Clark, and their crew arrived on 26 September 1805, at what they called Canoe Camp, on the Clearwater River.

Clearwater Canoe Camp Observations

30 September–6 October 1805

by Robert N. Bergantino

Determining the latitude of a location from a meridian observation of the sun is among the simplest celestial observations to take and to calculate. On 5 October 1805, Clark writes: “Latitude of this place from the mean of two observations is 46°34’56.3″ North.”

Colter’s Creek

Today's Potlatch River

by Joseph A. Mussulman

At 3 p.m. on 7 October 1805, the Corps loaded their five new dugout canoes–four large ones plus a small one “to look ahead”–and set out down the Clearwater River toward the Columbia and the Pacific beyond.

Meeting the Snake

Water color

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Corps’ four-day trip to this point from Canoe Camp on the Clearwater in their five crowded dugouts was a taste of things to come.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

Tucannon and Palouse Rivers

"rugid rocks"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Now they entered a four-mile-long torrent, its climax a “narrows or narrow rapid” through which a channel 25 yards wide was confined between “rugid rocks” for a solid mile and a half.

Monumental Rock

Clark's Ship Rock

by John W. Jengo

Dubbed “Ship Rock” on Clark’s route map, but now known as Monumental Rock, this distinct outcropping of the Lower Monumental Member of the Saddle Mountains Basalt is located on the south bank of the Snake River in Walla Walla County, Washington, just upriver of Lower Monumental Dam.

Snake River Rapids

"Stuk fast"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The boating didn’t improve on 14 October 1805. At the head of a particularly bad three-mile-long rapid, three canoes “Stuk fast for some time . . . and one Struk a rock in the worst part.”

Lake Missoula Floods

Route of the Lake Missoula Floods

by John W. Jengo

From the moment they dipped their paddles into the Snake River, the Lewis and Clark expedition would not only be following the path of multiple flood basalt flows, but also the route of the colossal Lake Missoula floods that so markedly scoured the basaltic landscape.

Meeting the Columbia

A welcoming fanfare

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In the afternoon of 16 October 1805, the expedition portaged around “the last bad rapid as the Indians Sign to us”–the last on the Snake River, that is–and soon arrived at the “Great River of the West,” the Columbia.

The Snake-Columbia Confluence Observations

17–18 October 1805

by Robert N. Bergantino

On 17 October 1805, at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers, Lewis set out the artificial horizon and got the sextant out of its case. One of the men stood by with the chronometer, ready to read and record the time of Lewis’s measurements.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.