First Visit

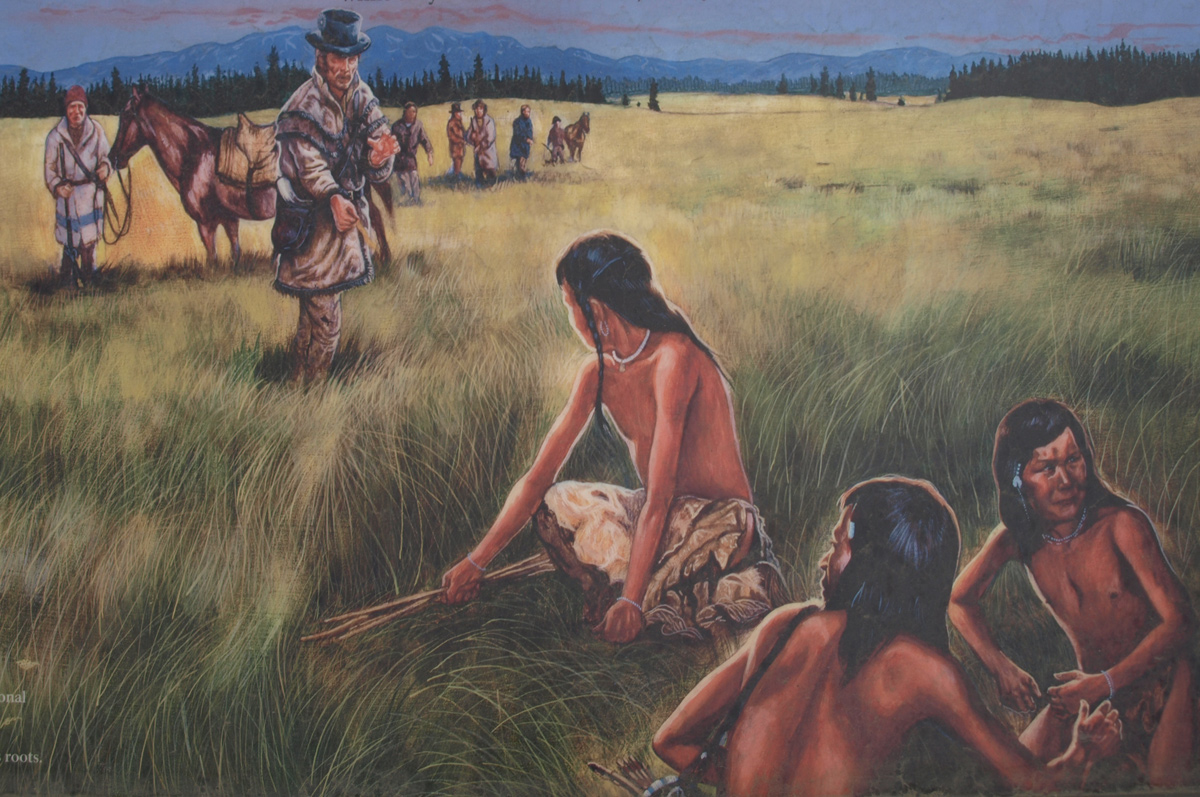

For countless generations, Weippe Prairie (prounouced WEE-yipe), like Travelers’ Rest, was a major node in the transportation, trade, and social networks of the Rocky Mountain West. Indians routinely covered the 140 miles between these two terminuses in “five sleeps,” or six days, but it took the Corps of Discovery eleven cold, wet, painfully hungry days on their late-season westbound journey. On 18 September 1805, two-thirds of the way through the mountains, Clark and six hunters pushed ahead of the main party in search of fresh meat. Two days later they left the mountains and “proceeded on through a beautifull Countrey . . . to a Small Plain” in which there were many Indian lodges. On the twenty-second, Lewis and the rest of the Corps arrived here, elated at having “tryumphed over the rocky Mountains.”

At Weippe Prairie, the explorers also experienced the hospitality–albeit tentative at the outset–of the people called Nez Perce, in an unfortunate misinterpretation of a sign-language gesture that seemed to indicate that they had “Pierced Noses.” Subsequently, French traders translated their manual sign into Nez Perce, pronounced in current English “nez-PURSE” or “NEZ-purse” not “nay-per-SAY”). The Nez Perce call themselves Tsoop-nit-peloo, “The Walking-Out People,” or Nee-me-poo, meaning “The People.”

Leaving Long Camp

Ford on Collins (present Lolo) Creek

for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

A packer and his partner coax a six-animal pack string through the Lolo (Collins) Creek ford on the trail between the Clearwater Canyon and Weippe Prairie. Judging from Lewis’s comment, it seems quite likely that the creek was considerably deeper and faster than this in early June, and the horses would have had to swim it with their riders aboard. In June, the rocks in the foreground would certainly have been underwater. With sixty-five horses to get across, it is a testament to the skill of the riders and packers that they all made it without an accident.

On the ninth of June Lewis noted that his men “seem much elated with the idea of moving on towards their friends and country.” They all “seem allirt in their movements today; they have every thing in readiness for a move.” Even though they had consumed the last of their meat the night before and had only roots left to eat, they devoted much of the day to running footraces, pitching quoits, and playing prisoner’s base.[1]Quoits is a team-game that the New Englanders in the Corps would likely have taught the others. It consists in tossing metal rings at pins driven into the ground. The players in the Corps might have … Continue reading There seemed to be good reason to celebrate; the river had fallen six feet in just a few days, which seemed to be “strong evidence that the great body of snow has left the mountains.” In a few more days, Lewis predicted, the roads would be dry and the grass would be greening up. The next day they climbed out of the Clearwater Canyon toward the “quawmash flatts,” and camped near the spot where they had first met the Nez Perce on the previous 20 September 1805.

Missing horses delayed the expedition’s departure from Long Camp until nearly noon on 10 June 1806, with each man “well mounted and a light load on a second horse.” Even at mid-afternoon Lolo (Collins) Creek was running high and fast, and the Corps’ crossing was “extreemly difficult” tho’ we passed without sustaining further injury than weting some of our roots and bread.” After a twelve-mile march, including a 1,800-foot climb out of Clearwater Canyon, they settled down at the “Commass ground” where they had camped the previous 22 September 1805.

Awash in Camas

Camas, Camassia quamash

Weippe, near Second Village

© 7 June 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

On their homeward journey, the Corps returned to Weippe Prairie on 10 June 1806. At the time, the prairie was awash in camas flowers; the blue blossoms rippling in the breeze reminded Lewis of “lakes of fine, clear water.” Indeed, this was a major source of the delicious, nutritious bulb of the camas–a wild vegetable equal in status to the potato for many Americans today. Ordway noticed that the soil was “very rich and lays delightful for cultivation.” Indeed it is, and that is why agriculture has permanently altered the prairie’s ecology.

We can imagine John digging a fistful of earth, squeezing it, sifting it between his fingers, sniffing his hand, squinting across the scene. Later, he smiles to himself as he writes, with a born farmer’s delight, “the Soil is deep black & verry rich & easy for cultervation.” (In fact, after the expedition was over he settled in Missouri, became a prosperous landowner, and developed two plantations of peach and apple orchards in famously fertile Tywappity Bottom, opposite the mouth of the Ohio.)

During the next four days, while the hunters worked the area for miles around, spring had arrived at the western edge of the mountains. “The quawmash is now in blume,” Lewis wrote, “and from the colour of its bloom at a short distance it resembles lakes of fine clear water.” So convincing was that “deseption that on first sight I could have swoarn it was water.” This was the right time and the ideal place for him to paint his crisply detailed word-picture of Camassia quamash and to record the Nez Perces’ method of cultivating and cooking the root.

Lewis put their situation in a serious perspective. “We have now been detained near five weeks in consequence of the snows,” he lamented:

a serious loss of time at this delightfull season for traveling, I am still apprehensive that the snow and the want of food for our horses will prove a serious imbarrassment to us as at least four days journey of our rout in these mountains lies over hights and along a ledge of mountains never intirely destitute of snow. every body seems anxious to be in motion, convinced that we have not now any time to delay if the calculation is to reach the United States this season; this I am detirmined to accomplish if within the compass of human power.

There was also a new element to prove that summer was coming on. “The Musquetoes our old companions have become very troublesome.”

A Third Visit

With, as Clark expressed it, “Some mortification in being thus compelled to retrace our Setps through this tedious and difficuelt part of our rout,” they left “Salmon Trout Camp” early on the twenty-first to return to “the flatts.” Dense brush and fallen timber made travel diffitult for the men and dangerous for the horses. One of Pierre Cruzatte‘s horses “snagged himself so badly in the groin in jumping over a parsel of fallen timber that he will evidently be of no further service to us.” At Collins’s Creek they met two Nez Perces who had in tow three horses and a mule that had wandered off the night before and returned to the camas grounds. The Indians told them they had seen Drouillard and Shannon, whom the captains had sent back to hire guides. At a disadvantage without Drouillard’s expertise in signing, the captains understood it would another two days before the two men could rejoin the party, but were at a loss as to why the delay.

The company’s disappointment was somewhat alleviated the next morning when “all hands who could hunt were sent out,” and returned with eight deer and three bear—fresh meat and plenty of bearfat! Encouraged by the rumor that the salmon were running, they sent Whitehouse down to the riverside villages to buy some fish with a few beads Clark had found in his waistcoat pocket.

On the twenty-third the hunters, by imitating the bleats of fawns, bagged four deer; as a bonus they brought in another bear. At last, late in the afternoon Drouillard, Shannon and Whitehouse appeared and introduced three Indians–”young men of good character and much respected by their nation”–who had consented to accompany them all the way to the Great Falls of the Missouri. After another day spent in gathering together the remnants of the party, including Frazer, Weiser, Gass, and the two Field brothers, the Corps of Discovery, reinforced with fresh meat, competent guides, and new hope, was at last prepared to “proceed on.”

Weippe Prairie is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. A 274-acre tract in the prairie is managed by the Nez Perce National Historic Park.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Quoits is a team-game that the New Englanders in the Corps would likely have taught the others. It consists in tossing metal rings at pins driven into the ground. The players in the Corps might have improvised rings from rope or willow branches. The long and fascinating history of this ancient pastime is summarized in the Web site of the U.S. Quoits Association at http://www.quoits.info. Prisoner’s base is a simple, formalized game of tag. Now considered a children’s sport, its age-old rules and procedures are explained at http://www.gameskidsplay.net/games/chasing_games/prisoners_base.htm. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.