Today the temperature of the water entering the outdoor swimming pool (the blue spot in the photo) is 86° Fahrenheit; that entering the smaller indoor plunge (scarcely visible to the left of the pool) is between 102° and 104°. Out of sight beyond the toe of the ridge at upper right is Granite Spring, which emerges from the granitic rock at 120°, and might be the one Clark tested with his finger.

The highway connects Missoula, Montana, with Lewiston, Idaho. Notice that the creek originally flowed around a bend on the far side of the highway (blue line) and close to the spring, but was relocated by highway engineers and since then has flowed in a straight-line cutoff on the near side of the roadbed.

At the Hot Springs

“These Springs are very beautiful to See, and we think them to be as good to bathe in &c. as any other ever yet found in the United States,” avowed Private Joe Whitehouse. The water was “considerable above blood heat.” In fact, it “nearly boiled where it Issued out of the rocks.” Clark’s reaction was quick. “I put my finger in the water, at first could not bare it in a Second.” [13 September 1805]

Clark noted that “as Several roads led from these Springs in different derections,” their Lemhi Shoshone guide, Toby, took a wrong turn and led them three miles out of their way over an “intolerable” road. The maze of roads seen in this photo, mostly created for log-hauling trucks, are now used by recreationists who visit the springs for hiking, mountain-biking, horseback riding, and for cross-country skiing in winter. Among them is what remains of the luge run built here in 1965—reportedly the first in North America.

The company paused here for only a few minutes on their way west, but on their return spent the whole night of 29 June 1806, which provided Lewis with sufficient time to describe the place and the experience.

these warm springs are situated at the base of a hill of no considerable hight on the N side and near the bank of travellers rest creek which at that place is about 10 yards wide. these spring issue from the bottoms and through the interstices of a gray freestone rock, the rock rises in iregular masy clifts in a circular range arround the springs on their lower side. immediately above the springs on the creek there is a handsome little quamas plain of about 10 acres. the prinsipal spring is about the temperature of the warmest baths used at the hot springs in Virginia.

In this bath which had been prepared by the Indians by stoping the run with stone and gravel, I bathed and remained in 19 minutes, it was with dificulty I could remain thus long and it caused a profuse sweat two other bold springs adjacent to this are much warmer, their heat being so great as to make the hand of a person smart extreemly when immerced. I think the temperature of these springs about the same as the hotest of the hot springs in Virginia.

Both the men and indians amused themselves with the use of a bath this evening. I observed that the indians after remaining in the hot bath as long as they could bear it ran and plunged themselves into the creek the water of which is now as cold as ice can make it; after remaining here a few minutes they returned again to the warm bath, repeating this transision several times but always ending with the warm bath.

Then and Now

“Hot Springs at Source of Lou Lou Fork

Bitterroot Mountains, Looking West”[1]Isaac Stevens, Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound (12 … Continue reading

by John Mix Stanley (1814–1872)

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

John Mix Stanley’s hand-tinted lithograph of this remote watering place possibly was the first ever published. It does not look west, but almost due south (190° from True North). At left is one of the rocks in the vicinity of the hot springs which, according to Sergeant John Ordway, “appear above the timber like towers in Some places,” although the most impressive “tower” is opposite this one and adjacent to the springs. To the right of the granite outcrop, in the “handsom green or Small meadow” are the bathing ponds Indians had created by damming the outflow of the springs, which are out of sight beyond the trees at right.

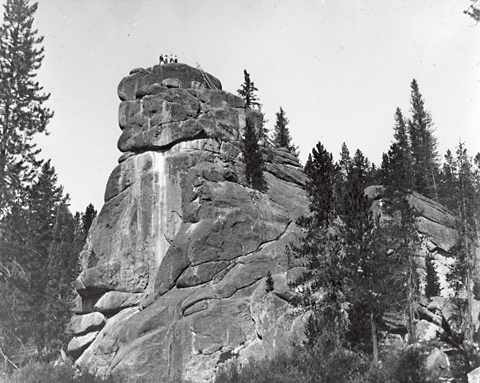

Rock above Lolo Hot Springs

Compare this view of the granite outcrop with the same feature in Stanley’s painting, particularly with regard to the spacing of trees. In the absence of small periodic ground fires to thin out new growth and thus reduce competition for nourishment, moisture, and sunlight, this landmark is now mostly obscured by a crowded forest of young Douglas-fir, spruce, and lodgepole pine. The tall trees on the horizon at center, reaching far above the crown of the lower, even-aged trees document the fact that most of the area pictured was extensively logged in the 1950s or 60s. All of the land in this photograph is privately owned.

A Natural Attraction

Chauncy Woodworth Collection, K. Ross Toole Archives, University of Montana, Missoula, No. 75-188.

“Masy clifts” of grey freestone rock, Lewis called them. Freestone, according to a contemporary dictionary,[2]Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (Hartford, Connecticut, 1806). denoted “a kind of grit, or sandstone” that could easily be split into slabs or blocks along natural fracture lines. Usually the term was applied to sandstone or limestone, but the conspicuous outcrops such as this one, which is adjacent to the hot springs on upper Lolo Creek, are granitic igneous rocks of the huge Idaho batholith that lies deeply submerged beneath the Bitterroot Mountains. Lewis and Clark must be forgiven for their errors in geological exploration, since the science was still young, and they were ill-prepared to deal with it (see Bitterroot Mountain Granite).

Our 21st-century obsession with personal cleanliness would have puzzled and perhaps even amused Lewis and Clark’s generation, situated as it was some three-quarters of a century B.B.—”before bacteria” were discovered. Although intimations of the real causes of “dis-ease” had occurred to a few scientists in the late 17th century, it was not until Louis Pasteur broke the barrier in the early 1880s that set in motion the sciences of bacteriology and immunology, and made civilization aware of what had been bugging humans since the beginning of time. Meanwhile, from the 1790s on, people patronized the new commercial public bath houses in eastern cities, unaware of how unhealthful they really were. Household conveniences were better only insofar as they kept the bacteria in the family. Not until 1883 were the first cast-iron bathtubs with easy-to-clean enameled interiors introduced into private homes, although only the well-to-do could afford them at the time. By the early 1920s only one percent of all homes in the U.S. had indoor plumbing, and even then running hot water was a rare luxury.

In northern latitudes, especially in cold weather, the best a person could do was stand within reach of a pan of hot water on the wood stove and wash up as far as possible, down as far as possible, and occasionally wash “possible.” Or one could put a few inches of cold water in a copper tub, fetch a teakettle of boiling water to mix with it, then hop in—standing, kneeling or, depending on the size of the bather, sitting—and scrub briskly before it cooled below comfort level. Unless one could call upon servants or slaves for help—as Jefferson, Lewis, and Clark could—even that routine was easiest for children and young adults. For the lame and the elderly it was usually not worth the effort. Perfumes, whether bought from a pharmacist or concocted of sweet herbs and alcohol, were more convenient. The general treatment for body odor was simply to get used to it. A person could go for years without getting wet all over at one time. In fact, many people considered it unhealthful to immerse one’s body in water, as evidenced by the disturbing, even frightening, observation that the flesh of one’s fingers shriveled up after a few minutes of soaking.

On the other hand, natural hot running water from a geothermal spring, which never cooled off and perpetually refreshed itself, represented the acme of pleasure and delight, not only for the sake of cleanliness but especially for the supposedly healthful effect of of the minerals in the otherwise pure water. The extent of that benefit was easily recognizable by the water’s smell and taste, both qualities usually being attributed to sulfur, whether or not there was actually any in it. Contemporary wisdom held that the smellier the water, the more healthful it must be. The worse the taste, the better. Private Joe Whitehouse of the Corps of Discovery noted, with perhaps some satisfaction, that several of the men drank the water from these hot springs and found that “it has a little sulpur taste and verry clear.”

Horse-drawn stage at Granite Hot Springs

Virginia Foster Photograph Collection, K. Ross Toole Archives, University of Montana, Missoula, No. 88-86.

The wagon road from Lolo to Granite Hot Springs was scraped into the narrow canyon in 1888 to make the hot springs more easily accessible to customers from town. Travelers were compelled to ford Lolo Creek 29 times in the 25-mile drive, which could be a worrisome prospect in the spring, when the water was swift, deep, and ice-cold.

Lolo Hot Springs

Virginia Foster Photograph Collection, K. Ross Toole Archives, University of Montana, Missoula, No. 88-80.

By 1910 there were 350 automobiles in Missoula, and the drive up Lolo Canyon to the springs was a standard test of the sturdiness and reliability of any vehicle. The building shown in both photographs was the hotel at Granite Hot Springs, a quarter of a mile from the others. This land and the springs are still privately owned, and are not now open to the public.

Notes

| ↑1 | Isaac Stevens, Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound (12 vols., Washington, D.C.: Thomas H. Ford, Printer, 1860), Vol. 5, Book 1, Plate 85. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (Hartford, Connecticut, 1806). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.