Lewis’s Description

Some of the leaves of Berberis aquifolium turn red or purple in winter, which may account for Lewis’s reference to the plant on two occasions as “red holly.”

In his journal for 12 February 1806, Lewis described the plant that now goes by the name Berberis aquifolium (or sometimes Mahonia aquifolia), which he had first noticed in the vicinity of the Cascades of the Columbia, about 145 miles from the ocean. A lower, scraggly and somewhat less conspicuous species of the same genus had been in plain sight most of the way from the east slopes of the Rockies, but evidently he had not paid much attention to it. The coastal form of it is taller and shrubbier.

The roots . . . are creeping [extending parallel to the surface of the ground] and cylindric.

The stem . . . is from a foot to 18 inches high and as large as a goose quill; it is simple [of one piece] unbranched, and erect.

Its leaves are cauline [growing from the upper part of the stem], compound [composed of two or more similar parts joined together] and spreading [diverging nearly at right angles].

The leaflets [one of the divisions of a compound leaf] are jointed and oppositely pinnate [opposed to each other at the node, or joint], 3 pair, and terminating in one, sessile [without a stalk], widest at the base, and tapering to an accuminated [tapered] point, an inch and a quarter the greatest width, and 3 inches and a 1/4 in length.

Each point of their crenate [with rounded teeth] margins [borders of the leaves] is armed with a subulate [awl-shaped, tapering to a point] thorn or spine . . . from 13 to 17 in number.

They are also veined [vascular ribs that form the branching framework of conducting and supporting tissues in a leaf], glossy, carinated [ridged] and wrinkled, their points obliquely pointing towards the extremity of the common footstalk [a supporting stalk].

Although Lewis was, as Jefferson wrote, “no regular botanist,” he was an able and experienced observer, and he had been an apt student of the eminent botanist Benjamin Smith Barton in Philadelphia, in preparation for the expedition. Furthermore, he took along several natural history reference books, including John Miller’s An Illustration of the Termini Botanici [botanical terms] of Linnaeus, Volume II (London, 1789) on which he relied heavily when writing his plant descriptions. His note on Berberis aquifolium demonstrates the economy with which the botanist’s terminology functions. We have inserted brief definitions in the following excerpts; the original text has been enhanced with modern punctuation and capitalization for readability.

Lewis’s Specimen

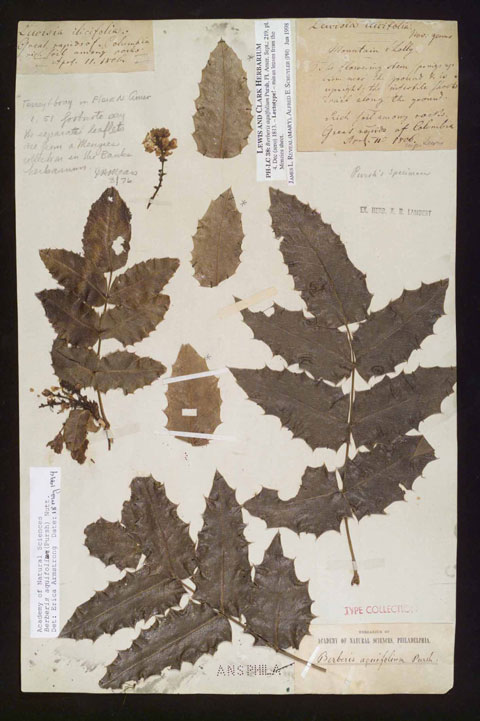

Botanists periodically review specimens such as Lewis’s in order to verify the work of their predecessors, or else to make corrections in the light of more recent discoveries. The notations on Lewis’s specimen sheet trace the record of scientific understanding of Berberis aquifolium during the past 200 years.

The notation at extreme upper left of the image above was written by Frederick Pursh, the German (Saxon) botanist who had come to the United States in 1799, and who was given Lewis’s entire collection of herbarium specimens for study and classification. It reads: “Lewisia ilicifolia. Great rapids of Columbia with soil among rocks. April 11, 1806.”

Pursh first thought the plant represented a new genus, which he considered naming Lewisia in honor of Meriwether Lewis. After further study, however, he decided it properly belonged to an existing genus, Berberis, and that is the one he used in his book, Flora Americae Septentrionalis (Plants of North America), published in 1813.

Ilicifolia (ee-li-ki-FO-lee-uh) is a Latin noun denoting evergreen trees and shrubs; the root of the word is ilex, which is Latin for holly.

The memorandum in the upper right-hand corner, also in Pursh’s handwriting, reads: “Lewisia ilicifolia Nov: genus [new genus]. Mountain Holly. The flowering stem Springs up from near the ground & is upright; the infertile Shoots trail along the ground. Rich soil among rocks. Great rapids of Columbia. April 11th 1806.”

Lewis concluded his detailed description of the plant on 12 February 1806, with the observation that it “resembles the plan common to many parts of the U’ States called the mountain holley.”

The note “copy Lewis,” faintly visible below the date, may have been entered by Thomas Meehan, the botanist at the Academy of Natural Sciences who found the long-neglected Lewis and Clark herbarium at the American Philosophical Society in 1896.

Beneath this label is written “Pursh’s specimen.” The rubber-stamped words are: “Ex. [from] Herb[arium of] A. B. Lambert.”

Pursh took most of Lewis’s specimens to London in 1811, and worked on them there under the patronage of A. B. Lambert, a wealthy cabinet—that is, laboratory—botanist. The collection remained in Lambert’s custody from the time of Pursh’s death in 1820 until his own death in 1842, after which part of it was purchased at auction by a wealthy young American botanist, Edward Tuckerman. Fourteen years later, Tuckerman gave the Lewis and Clark specimens to the Academy of Natural Sciences.

The handwriting at left, just below Pursh’s note, reads: “Torrey & Gray in Flora N. Amer 1:51 footnote say the separate leaflets are from a Menzies collection in the Banks herbarium.” It is signed “J. A. Mears 3/ [19]76.” Mears was a curator at the ANS.

The reference is to Flora of North America, by John Torrey and Asa Gray (2 vols., New York: 1838-40). James Mears was a botanist at the Academy in the 1970s.

Sir Joseph Banks obtained many specimens gathered by naturalists around the world which he added to his own extensive collections that he had obtained mainly in Newfoundland and Australia. The Banks herbarium is now part of the general herbarium of The Natural History Museum in London.

The typewritten label at lower left reads: “Academy of Natural Sciences/Berberis aquifolium (Pursh)/Det[ermined by]: Erica Armstrong/Date: 18 May 1994.”

Aquifolium, or “water leaf,” suggests the shiny, wet-looking surface of the plant’s leaves. Botanist Erica Armstrong recently worked at the Academy.

The printed label at center top reads: “Lewis and Clark Herbarium/Ph.L.C.38: Berberis aquifolium Pursh, Fl. Amer. Sept.: 219. pl[ate].4. Dec (sero) 1813. –Lectotype!–minus leaves from the Menzies sheet. James L. Reveal (MARY [University of Maryland]), Alfred E. Schuyler (PH [Academy of Natural Sciences]) Jun 1998.”

Exclusive of the three pale leaves in the center, which came from a collection made by Archibald Menzies (see below), the three specimens Pursh studied constitute a “lectotype.” The “type” method of plant classification was designed to stabilize the ranking of species by scientists. Accordingly, the first botanist to describe and name a plant establishes his specimen as the original type material, or “holotype.”

But the type method was not introduced until after Pursh’s death, so a later botanist has designated Pursh’s (Lewis’s) specimen as a substitute for the undesignated holotype of Berberis aquifolium.

In 1790, Archibald Menzies, a Scottish physician and naturalist, was appointed by the British government to accompany Captain George Vancouver on a global tour in the good ship Discovery. His primary responsibility was as the ship’s surgeon. His natural history responsibilities included making observations on plants, recording their scientific as well as Indian names, and noting whether English settlers might be able to thrive in each place as farmers.

Alfred E. Schuyler is curator of the Lewis and Clark Herbarium at the ANS.

For many years this plant was known as Mahonia aquifolium (Pursh) Nutt. “Nutt.” stands for Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), an English naturalist who came to the U.S. in 1808 and studied botany under Benjamin Smith Barton, one of Lewis’s mentors. Nuttall renamed the genus Mahonia in honor of Bernard McMahon (c. 1775-1816), the prominent horticulturist in whose Philadelphia home Pursh began the study of Lewis’s specimens.

At the time of this writing, the accepted name is Berberis aquifolium.

Hooker’s Engraving

Hand-colored engraving of Berberis aquifolium

from Pursh’s Flora Americanae Septentrionalis

Drawn & Engraved by William Hooker[1]William Hooker (1779–1832) was a British botanist and botanical artist employed by the Royal Horticultural Society of London.

Courtesy of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. Unauthorized use prohibited.

The details illustrated at the bottom of Hooker’s Engraving:

- (right) The undersurface of a leaf.

- Undersurface of the flower showing three greenish bract-like structures (bracteoles) that subtend the flower proper, with the two whorls of yellowish sepals. On the left is the broad outer sepal (one of three) and next to that is the longer and narrower inner sepal (one of three). Unlike most flowers, the flowers of Berberis have six large and obvious sepals arranged in two whorls of three.

- The small, bi-lobed petal (one of six arranged in two whorls of three) with an associated stamen (one of six opposite each petal).

- Detail of the stamen depicting the broad filament with a pair of recurved lateral teeth

- An ovary with three terminal stigmatic lobes.

Barbary Berry

” . . . to the shores of Tripoli . . .”

Thomas Jefferson took close personal interest in the fortunes of the Expedition, and especially its discoveries in the field of natural history, but he had other important things on his presidential mind, too, such as piracy.

Soon after Jefferson’s first inauguration, in the winter of 1800, the pasha of Tripoli declared war on the United States because he was receiving smaller ransom payments for the American sailors and ships he captured than were his fellow terrorists at Algiers. Jefferson responded by committing a small naval force to the Mediterranean Sea, empowered with a surge of patriotic support at home.

The critical point came in February 1804 (while at Camp Dubois the Corps of Discovery was poising for departure). Lieutenant Stephen Decatur boldly sailed his ship Enterprise into the harbor at Tripoli and burned the U.S. frigate Philadelphia, to void its captors’ demands for tribute, incidentally avenging his own brother’s death with the blood of a few privateers. He carried off the whole engagement at the cost of only one man wounded.

It was, as Lord Nelson of the British Admiralty said, “the most bold and daring act of the age.” Twenty-five-year-old Decatur instantly became an American hero of a stature and popular appeal that neither Lewis nor Clark attained for more than a hundred years.

His famous reply to a congratulatory toast inspired his nation for most of the 19th century: “Our country! In her intercourse with foreign nations may she always be in the right; but our country, right or wrong!”[2]For more, see on this site Jefferson’s Barbary Coast War.

When Lewis wrote his description of this new plant in February 1806 he remarked that he had not yet observed its fruit or flower, but the specimen he brought back, which he collected in April while en route up the Columbia River, does include Berberis aquifolium in flower.

Pictured above is the blossom of Berberis repens (creeping berberis), which would have been conspicuous on the forest floor of the Bitterroot Mountains in June, though none of the journalists mentioned it. A few of the late-summer fruits may still be seen in early spring if local birds haven’t eaten them all. The hand-colored engraving of Berberis aquifolium from Pursh’s Flora Americae Septentrionalis (see above) includes a blossom, though the yellow is much paler than normal.

Some botanists once considered B. aquifolium and B. repens to belong to the same species. However, the former grows up to six feet tall, and has shiny leaflets; the latter is seldom more than one foot tall, and has thin, dull green leaflets.

Lewis never used the name Berberis aquifolium. It was Frederick Pursh who recognized the plant as belonging to the family Berberidaceae, and had sufficient knowledge and experience to be able to distinguish the species Lewis brought home, from B. vulgaris, or “common” Berberis.

But it is likely that, as Jefferson’s secretary, Lewis had learned a great deal about the people whose name the genus in question already bore, and to whose homeland Berberis vulgaris was native.

Since the second millennium B.C. the Berbers had occupied the entire Mediterranean coast of Africa—Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, the infamous Barbary Coast. From the 16th century, when ocean commerce began to increase, until the early 19th century, they were notorious for their piratical behavior (see below).

If Lewis learned anything about the ethnobotany of what he called “mountain holly” and many of his contemporaries called “barberry,” he never wrote of it in his journals, so we can’t say whether he knew that Indians knew the berries, though sour, could be eaten raw, or that their juice tastes much like grape juice, and makes excellent jelly. Or that the alkaloid (berberine) in the roots stimulates involuntary muscles, and a tea made of them could help delivery of a placenta. Or that herbalists of his own time—maybe including his own mother—considered it an excellent blood tonic, kidney medicine, diuretic, and antiseptic. Or that it could be used to doctor horses. He might have been especially glad to learn that the Salish Indians drank the tea for treatment of both gonorrhea and syphilis.

He might have heard that many Indians boiled the shredded bark of the plant to produce a brilliant yellow dye.

But he could not have known that more than a century in the future Berberis aquifolium would be declared the official flower of the State of Oregon.

Further Reading

Jeff Hart, Montana: Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society, 1976), pp. 25-27.

Gary E. Moulton, editor, The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (12 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–99), vol. 12, Herbarium of the Academy of Natural Sciences, 108 and plate 109.

James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark Collections of Vascular Plants: Names, Types, and Comments.” In Proceedings of The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (1999) 139:1–64.

Terry Willard, Edible and Medicinal Plants of the Rocky Mountains and Neighbouring Territories (Calgary, Alberta: Wild Rose College of Natural Healing, 1992), pp 98-99.

This page has been reviewed by Richard M. McCourt, Associate Curator of Botany, Academy of Natural Sciences,

and James L. Reveal, formerly of the Norton-Brown Herbarium, University of Maryland.

Notes

| ↑1 | William Hooker (1779–1832) was a British botanist and botanical artist employed by the Royal Horticultural Society of London. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For more, see on this site Jefferson’s Barbary Coast War. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.