Three Variations

Among biologists in general, and botanists in particular, says Mark Behan, there are “lumpers,” and there are “splitters.” The lumpers like to keep the science simple, and they minimize the number of species names; the splitters prefer to be more specific, and name “new” species and subspecies.

Populus tricocarpa (“people’s tree with hairy fruits”), which botanists now class as Populus balsamifera (bal-sum-IF-er-a, “aromatic”) is but one of three different species of cottonwood Lewis and Clark found in Montana. The other two species are angustifolia (“narrow leaf”) and deltoides (“triangular,” from the Greek delta), or plains cottonwood. But Mother Nature hasn’t read the books, and she doesn’t condone generalizations, especially when it comes to cottonwoods. She seems to favor the splitters.

Sometimes cottonwood species are hard to distinguish from one another. The leaves on the left, above, appear to belong to Populus tricocarpa or balsamifera because they are broad, dark green, and shiny, at least compared with those on the right. Those on the right from a nearby tree, are narrower, more lance-shaped, and lighter green, which might be taken to indicate Populus angustifolia. However, the cottonwood tree’s grip on life is so tenuous that Nature allows it to hybridize in order to prevail. These two instances are essentially balsamiferae, with some angustifolia in their blood. This, incidentally, illustrates one reason botanists don’t rely on leaves to determine the identities of plants, but rather on fruits.

Black Cottonwood

Black cottonwood grows quickly to heights of 80 to 125 feet—up to 200 feet in bygone days, along the lower Columbia River—and diameters up to four feet or more. The men of the Corps of Discovery probably carved twelve of the seventeen dugout canoes they made en route from either black cottonwood or plains cottonwood.The remaining five were carved out of ponderosa pine logs on the Clearwater River in Idaho, in September 1805.[1]Black cottonwood weighs 23.5 pounds per cubic foot. Assuming a canoe carved from a 30-foot black cottonwood log 40 inches in diameter, with a hull averaging four inches in thickness, and allowing for … Continue reading

The leaf bud pictured at left is the feature containing a sticky black substance that gives the black cottonwood its proper botanical name. Balsam is “any of several aromatic resins . . . that contain considerable amounts of benzoic acid, cinnamic acid, or both, or their esters.”[2]American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition.

The leaf bud pictured at left is the feature containing a sticky black substance that gives the black cottonwood its proper botanical name. Balsam is “any of several aromatic resins . . . that contain considerable amounts of benzoic acid, cinnamic acid, or both, or their esters.”[2]American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition.

Regrettably, interactivity on the World Wide Web is confined to the provinces of sight, sound, and the imagination, and there is no imaginable way in which the heady essence of Populus balsamifera can be conveyed in ones and zeros. For the present, at least, you have to be there.

Leaves

Here’s one way to determine whether the narrower leaf pictured on the preceding page is from a narrow leaf (angustifolia) or a black cottonwood. First, the leafstalk, also called the petiole (Latin for “leafstalk”), of an angustifolia leaf is less than one-third the length of the midrib. Second, the angustifolia leaf is the same shade of green on both sides. Most likely the leaf pictured above is from a Populus balsamifera, or black cottonwood, whose own seed was pollinated by a Populus angustifolia, giving it narrower leaves than a full-blooded black cottonwood.

Further comparison makes the identification process easier. At left is a true Populus angusti-folia. Notice that the petiole is less than one-third the length of the midrib. The leaf on the right, with the long petiole, is from a Populus deltoides, or Plains and eastern cottonwood. Also, the edge (margin) of the latter is deeply notched (crenelated), while that of the angustifolia is less so, and the balsamifera’s is smooth. Also, the deltoides leaf is the same deep green on both sides, while the hybrid, like the angustifolia, is lighter on the underside.

On 12 June 1805, the day before he reached the Great Falls of the Missouri, Meriwether Lewis wrote his own brief description of the species previously unknown to science:

The narrow leafed cottonwood grows here in common with the other species of the same tree with a broad leaf or that which has constituted the major part of the timber of the Missouri from it’s junction with the Mississippi to this place. The narrow leafed cottonwood differs only from the other in the shape of it’s leaf and greater thickness of it’s bark. The leaf is a long oval acutely pointed, about 2-1/2 or 3 Inches long and from 3/4 to an inch in width; it is thick, sometimes slightly grooved or channeled; margin slightly serrate; the upper disk of a common green while the under disk is of a whiteish green; the leaf is smooth. The beaver appear to be extremely fond of this tree and even seem to scelect it from among the other species of Cottonwood, probably from it’s affording a deeper and softer bark than the other species.

On 26 July 1806, just after departing from “Camp Disappointment” in the upper Marias River basin, Lewis astutely noted:

here it is that we find the three species of cottonwood which I have remarked in my voyage assembled together. That species common to the Columbia [balsamifera] I have never before seen on the waters of the Missouri, also the narrow [angustifolia] and broad leafed [deltoides] species

Fruit

In the spring—early April around Travelers’ Rest—male trees ship pollen (fiber so fine that it’s perceivable only by the sinuses of allergic humans) on the wind to any and all available female trees, to fertilize their flowers. The next stage is the emergence of the fruit.

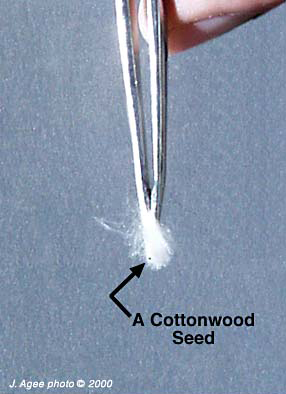

Each female cottonwood tree produces thousands of fruits, and inside the husk of each are hundreds of seeds. The white, cottony filaments are the sails by which the seeds will be dispersed by other winds. Each female cottonwood tree, depending on its size, may produce millions of seeds.

The seeds are so small, as you can see on the following page, that they contain no food reserves, so those that germinate are the comparatively few that luck onto the ideal homesite. In the short term, that means a successful seed must alight on soil that is soft and moist, which means close to the edge of the stream. Furthermore, there must be no other vegetation nearby to compete for available water. If those conditions are met, the seed immediately begins to send down a root, which follows the water table as it recedes during the future tree’s first summer. In the long run, it must be far enough away from the stream that a winter’s ice will not scrape it away while it is still young.

At best, life is hard for a young cottonwood tree. To grow and thrive it needs as much sun as it can get, so if other trees, even other cottonwoods, are too close, it must spend extra energy to stay in the light. Besides, cottonwood trees contain a lot of sugar, and it’s a fortunate seedling or sapling that escapes a wild ungulate’s appetite.

Seeds

The fruit ripens until the pods, now dry, burst like popcorn, presenting their seeds for the wind to distribute. Nature has scheduled this part of the process to take place over several days for each tree, timed to coincide with the peak of spring runoff, or just after the peak, so that silty places along the banks will still be wet enough to satisfy the seeds’ immediate need for water. The florescence in the middle of the photo above has surrendered nearly all of its seeds; the upper one has bided its time.

On windy days the result is a blizzard of cotton. This tree may well be losing ground along Montana’s rivers and streams, but in urban settings it can be such a nuisance that many cities prohibit the planting of female cottonwoods.

Missouri River Changes

This view of the Missouri River in the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, a few miles upstream from Fort Peck Reservoir in eastern Montana, illustrates Ms. Manning’s point. The cottonwoods across the river to the right appear to be “senior citizens” of the species, standing in orderly rows parallel to the water’s edge where they took root at the brinks of spring floods some sixty to eighty years ago. Between the trees and the water’s edge today is an expanse of brush trimmed with a margin of gravely riverbank only a few yards wide. A similar contrast may be seen in the background on the opposite side of the river.

Visions and values change. The first major dam on the Missouri River was built in 1892 at Black Eagle Falls, nearly 200 miles upstream from this point. Eight more mainstem dams followed—in 1910, 1911, 1915, 1918, 1930, 1940, 1958 and 1965—within the 210 miles between the Great Falls and the Three Forks of the Missouri, plus one dam on the Beaverhead, one on the Marias, and one on the Milk, each partly if not solely for the purpose of water conservation and flood control. Meanwhile, hundreds of smaller earthen dams were built on farms and ranches along the Missouri’s tributaries to impound water for agricultural use. Aside from all that, its main channel was laboriously manicured—”cleaned up”—for the convenience, safety and economy of commercial steamboat traffic during the middle half of the nineteenth century.

As much as we might wish to idealize, to romanticize the federally designated Wild and Scenic Missouri River, it scarcely represents what the Corps of Discovery saw in 1805-06. It is still scenically beautiful, but that scenery is by no means as dense and varied as it was back then.

Oyster Mushrooms

Perhaps no one other than a “shroomer” will ever notice or care, but departing cottonwood habitats take with them the Pleurotus ostreatus (plu-RO-tus = “layers”; os-tree-AYE-tus = “oyster”), or “oyster mushroom,” which emerges from dead cottonwoods in spring and fall. It is edible and, as is known today, is medicinally useful in reducing cholesterol.

Mushrooms are mentioned by the journalists only once. On 19 June 1806, Pierre Cruzatte brought Captain Lewis several large morels—possibly black morels, Morchella angusticeps (mor-CHELL-a = “Moorish,” ang-goo-STY-ceps = “narrow”), or sponge morels, Morchella esculenta (es-koo-LEN-ta =”edible”). Lewis roasted and ate them “without salt pepper or grease,” and found them “truly an insippid taistless food.” Fortunately for them, Cruzatte’s knowledge of the morel was accurate, and he evidently knew better than to recommend any other species to his Corps mates.

This photo was taken on 13 May 2000. The group of apparently dead trees to the right sprang to leaf just one week later, illustrating that, as botanist Mark Behan puts it, “Nature backs its bets.” They have been programmed to awaken—”break dormancy”—a little after the rest of the stand, in case a late hard frost nipped the others in the bud and prevented them from propagating.

At Traveler’s Rest

The stream the Lewis and Clark Expedition visited in 1805 and 1806, and called “Travelers’ Rest Creek”—known as Lolo Creek since the mid-19th century—flows eastward, from left to right, only a few yards beyond the line of cottonwoods in the background. The trees in the foreground have sprung up along some meanders of the creek that may have been flowing when the Expedition paused here in the fall of 1805 and spring of 1806.

Most of the trees in this stand range from 75 to 100 feet in height, and are from 20 to 60 years old, with a few between 60 and 100 years. They are distant offsprings of the cottonwoods that shaded the creek when the Corps of Discovery camped on the benchland behind the photographer.

The rancher who occupied much of the land in this vicinity for 35 years before it became a state park fed his cattle on the grass, and kept the area cleared of brush and dead trees. Since this area had been a major crossroads on the Indians’ intramontane transportation route for countless generations, subjecting it to heavy grazing by their huge herds of horses since the mid-18th century, and using its wood for campfires, it is conceivable that it looked pretty much like this to Lewis and Clark and their party.

Cottonwood trees still thrive along Lolo Creek in the vicinity of the ancient Indian campsite Lewis and Clark dubbed “Travelers’ Rest.” This scene, photographed early in May, 2000, may resemble the view the Corps of Discovery saw on their return here at the end of June 1806. There are no dams anywhere on Lolo Creek, and nearby residents have kept their livestock from grazing on the the banks, so the propagation of trees and shrubs has continued without major interruptions, as the slender young trunks along the bank attest. However, in many places along Lolo Creek and nearly every other stream in the West, some people are building homes within a few yards of the water, even on the floodplain, at best confining cottonwoods and other riparian vegetation to botanical ghettos, at worst cutting them down so they don’t “spoil the view.”

The red-orange brush across the creek is one of the numerous species of willow (Salix = SAY-lix, Latin for “willow”), not yet sprung to leaf. In August the small white blossoms faintly discernible at extreme left will become sweet, mealy serviceberries (Amelanchier alnifolia, a-me-LAN-kee-er [a Provençal name for serviceberry] al-ni-FO-lee-a, “alder-leaved”).

Poplars at Travelers Rest

Before the Corps of Discovery camped here on 9 September 1805–11 September 1805, and 30 June 1806–3 July 1806, this place they called “Travelers’ Rest” had been a heavily used campsite for many centuries. It continued to be used by both Indian and Euro-American travelers for at least 60 years afterward.

Travelers’ Rest State Park opened in 2002. The Travelers’ Rest Preservation Project is directed by the nonprofit Lolo Community Development Corporation.

Snow covered North Lolo Peak (elevation 9,096 feet) is faintly visible against the high, thin clouds, to the right of the somewhat snowy lower mountain in center background.

The tall trees to right of center are Lombardy poplars (Populus nigra), which were cloned in northern Italy before 1750 and imported into North America later in the 18th century as ornamentals. All Lombardy poplars are males, and propagate only by root sprouts. It has been said they were planted by Mormon settlers because their distinctive shape would signal to travelers that the land was occupied by members of the Church of Latter Day Saints.

Old Cottonwood Tree

© 2000 by J. Agee.

A Venerable Elder

This venerable elder of the local cottonwood community has survived perhaps a full century of the westerly winds that sweep down Lolo Canyon, and now stands 115 feet tall. Cottonwood trees don’t like shade, so its neighbors, with their youthful light gray bark, have shed their lower limbs to conserve energy as they reach for their share of sunshine.

Further Reading

Donald Culross Peattie, A Natural History of Western Trees (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), pp. 324-330.

Elbert L. Little, National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Western Region (New York: Knopf, n.d.), pp. 341-345.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Mark Behan to write this article.

Notes

| ↑1 | Black cottonwood weighs 23.5 pounds per cubic foot. Assuming a canoe carved from a 30-foot black cottonwood log 40 inches in diameter, with a hull averaging four inches in thickness, and allowing for a little tapering at the bow and stern, approximately how much would the dugout weigh, empty? The hard, strong, fine-grained ponderosa pine wood weighs 29.5 pounds per cubic foot. Given boats of identical size, how much more weight did the men have to lug around the Great Falls of the Columbia than around the Great Falls of the Missouri, per canoe? |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.