First Encounters

Common Chokecherry

Prunus virginiana

© 28 July 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The common chokecherry bush above was growing near the Knife River Villages where Little Crow and his wife resided.

As they towed, poled, and sailed the boats up the Missouri in the summer of 1804, the journalists took note of a wild cherry different than Prunus serotina—commonly called the black cherry and a common wild cherry of Kentucky and Virginia. The two plants are closely related, but the common chokecherry is a suckering shrub that can reach 30 feet whereas the black cherry is a tree that can reach upwards of 100 feet. The latter has smaller, darker berries and large leaves more bluntly edged than the finely serrated common chokecherry leaf.

At Nebraska’s Big Nemaha River on 12 July 1804, William Clark was the first to mention the common chokecherry:

I got grapes on the banks nearly ripe, observed great quantities, of Grapes, plums Crab apls and a wild Cherry, Growing like a Comn. Wild Cherry only larger & grows on a Small bush[1]12 July 1804, The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed., 2:368.

A week later and just below the Platte River, the enlisted men appear to give special notice to the common chokecherry. On 19 July 1804, Sgt. Charles Floyd wrote:

we Set out errly this morning prosed on passed a Run on the South Side Has no name we Called Cherry Run the Land is High Cliefts and pore whare a Grate nomber of thos Cherres thay Gro on Low Bushes about as High as a mans hed[2]Journals, 9:388.

Sgt. John Ordway and Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse held a culinary interest in the cherries at Floyd’s “Cherry Run.” In the words of Whitehouse “the men pulld a Great Quantity of wild Cherrys put them in the Barrel of whisky.”[3]Journals, 11:41. Infusing wines and spirits with cherries was not a new invention—even in 1804. The Potawatomis were known to add chokecherries to their wine.[4]Huron H. Smith, “Ethnobotany of the Forest Potawatomi Indians,” Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 7, no. 1 (9 May 1933): 109–10, … Continue reading Today, cherries and whiskey remain a popular flavor combination. There are numerous commercial cherry-whiskeys, and the Internet provides nearly unlimited recipes for making your own blend. There is even a winery not far from the mouth of the Nemaha River named Cherry Run. For the excited enlisted men, it was almost a certainty that it was the common chokecherry that was added to the whiskey barrel.[5]Regarding alcohol on the expedition, see on this site Alcohol Rations.

A Mandan Treat

Common Chokecherry Leaves and Fruit

© 26 July 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

These wild cherries were growing on a low bush along the Missouri River near Brockton, Montana.

Native peoples living along the Missouri River used the common chokecherry for food and medicine long before the expedition’s barge passed their homelands.

On a “fine Day,” 23 December 1804, Little Crow (or Little Raven) brought his wife and son to Fort Mandan loaded with corn. After Lewis gave them a few presents, the captains witnessed Little Crow’s wife make a special “treat” made from garden produce and chokecherries:

She made a Kettle of boild Simnins [squashes], beens, Corn & Choke Cherris with the Stones which was paletable

This Dish is Considered, as a treat among those people . . . .[6]William Clark, Journals, 3:261.

From Clark’s journal, we know that the Mandans used wild cherries as a winter food as did many other North American tribes. The ripe fruits were eaten raw and added to both staple and ceremonial foods. The berries could be pounded, dried, and mixed with fat. The prepared berries were then added to soups, pemmican, or stored in flat cakes for future use. The Blackfeet used the juice as a special drink to honor husbands or children and the Lakota Sioux made a tea from the leaves for use during the Sun Dance.[7]Shelly Katherene Kraft, “Recent Changes in the Ethnobotany of Standing Rock Indian Reservation”, M.A. Thesis (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, University of North Dakota … Continue reading Omahas, Pawnees, and Poncas also prepared the fruit for use in “old-time ceremonies.”[8]Melvin R. Gilmore, “Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, Number 33, 1919), 88, 89, as Padus … Continue reading Blackfeet would poke roasting meat with chokecherry sticks to add flavor.[9]John C. Hellson, “Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians,” National Museum of Man Mercury Series, no. 19 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974), 104, … Continue reading

Today the common chokecherry is a popular jam, can be added to wines and spirits, and its bark is often brewed by modern herbalists to treat coughs and colds.[10]Betty B. Derig and Margaret C. Fuller, Wild Berries of the West (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2001), 142.

The pits and leaves from most varieties of cherries, including the common chokecherry, contain toxins and poisons harmful—possibly fatal—to humans and ruminant livestock. Luckily, no illnesses from eating the Mandan treat were reported.

Medicinal and Other Uses

P. virginiana had—and still has, many medicinal uses. That it was effective as a gastronomic aid would not be surprising to the Blackfeet, Cheyennes, Flathead Salish, and Atsina who also infused the bark or consumed the juice or fruit for such illnesses.[11]Jeffrey A. Hart, “The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 4 (1981): 88. The plant also had wide-spread use for coughs, sore throats and colds.[12]Moerman, 445.

Blackfeet used the berry juice as an anti-diarrheal and for sore throats and mixed the cambium layer with serviceberry to make a purgative. The latter infusion was also given to nursing mothers to pass the medicinal benefits on to the infant. Nursing Blackfeet mothers also drank chokecherry tea believing the medicinal properties would pass on to the child.[13]Hellson, 68.

For diarrhea or dysentery, Cheyenne adults pulverized the immature berries, and their children ate them whole. For the same malady, the Flathead Salish infused the bark. They also used the bark’s resin as a treatment for sore eyes.[14]Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1976), 88–89; Hart, “The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana,” 35.

The Blackfeet used the wood to make cooking utensils and digging sticks.[15]Hellson, 94, 104. Lakotas and Cheyennes used the wood for arrow shafts and bows and the Crows made tepee stakes. The Crows also used the plants’ sap to make glue. Some Montana Indians added the sap to colored clays to make paint.[16]Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples, 89.

Common chokecherry’s cambium layer—the inner bark—was sometimes used to extend tobacco in various mixtures called kinnikinnick.

Botanical Description

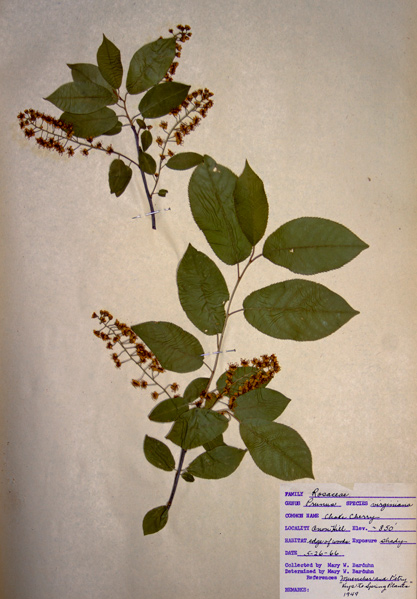

Common Chokecherry

Prunus virginiana var. virginiana

Courtesy Herbarium of Baltimore Woods. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

According to it’s label, the specimen shown here was collected by Mary W. Barduhn at Onon Hill [New York?] in a shady exposure at the edge of woods on 26 May 1966.

Lewis’s Description

Prunus virginiana, the common chokecherry, was not new to science. The father of modern botany, Carl Linnaeus, described the plant in 1753.[17]“Prunus virginiana,” Flora of North America, www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=242417061, accessed 20 February 2023. Lewis wrote his description on 12 May 1805, the day he walked the shore above present-day Fort Peck Dam. The area is in the transition zone between two varieties, P. virginiana var. virginiana and P. virginiana var. melanocarpa, commonly called the black chokecherry. Lewis wrote:

the choke Cherry has been in blume since the ninth inst. this growth has freequently made it’s appearance on the Missouri from the neighbourhood of the Baldpated Prarie, to this place in the form of it’s leaf colour and appearance of it’s bark, and general figure of it’s growth it resembles much the Morillar cherry, tho’ much smaller not generally rising to a greater hight than from 6 to 10 feet and ascociating in thick clusters or clumps in their favorit situations which is usually the heads of small ravines or along the sides of small brooks which flow from the hills. the flowers which are small and white are supported by a common footstalk as those of the common wild cherry are, the corolla consists of five oval petals, five stamen and one pistillum, and of course of the Class and order Pentandria Monogynia. it bears a fruit which much resembles the wild cherry in form and colour tho’ larger and better flavoured; it’s fruit ripens about the begining of July and continues on the trees untill the latter end of September— The Indians of the Missouri make great uce of this cherry which they prepare for food in various ways, sometimes eating when first plucked from the trees or in that state pounding them mashing the seed boiling them with roots or meat, or with the prarie beans and white-apple; again for their winter store they geather them and lay them on skins to dry in the sun, and frequently pound them and make them up in small roles or cakes and dry them in the sun; when thus dryed they fold them in skins or put them in bags of parchment and keep them through the winter either eating them in this state or boiling them as before mentioned. the bear and many birds also feed on these burries.[18]Journals, 4:145–46.

Lewis could well have prepared a specimen of the common chokecherry similar to the one above. If he did, it would have been one of those destroyed in a flooded cache at the Falls of the Missouri. His specimens of black chokecherry, P. virginiana var. melanocarpa, and bitter cherry, P. emarginata, likely contained a similar amount of material, as they too were blooming when he collected them at Long Camp at Kamiah, Idaho.

Botanical Terms

In his botanical description, Lewis made a rare use of two Botanical Latin terms, a specialized form of Latin that was in development during the Age of Enlightenment. Both Petandria and Monogynia—defined below—were present in the three botany books that Lewis had with him at the time. The following table shows the influence of those three books. Lewis’s alternated spellings are place within square brackets.

| Term | Definition | Barton Count | Miller Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| corolla [corolla, corollar] |

The petals surrounding the stamens and pistils, Barton 131; “the second whorl of floral organs, inside or above the calyx and outside the stamens” Kew 33 | 230 [corolla, corollarium, corollam, corollas] |

192 [corolla, corollia] |

| footstalk [footstalk, footstalks, fotstalk] |

“petiole” Barton 40; a petiole is a “leaf stalk,” Harris 84 | 53 [foot-stalk, foot-stalks, footstalk, footstalks, foot stalk, foot stalks] |

25 [footstalk, footstalks] |

| Monogynia | taxonomy order with “only one style, or female organ” Barton, part 3 page 4 | 33 | 27 |

| oval [oval, ova] |

“round” Barton 193 | 4 | 16 |

| Pentandria | A taxonomy class with “hermaphrodite flowers which are furnished with five stamens, or male organs” Barton, part 3 page 17 | 41 | 18 |

| pistillum | “the female part of the vegetable . . . . it consists of three parts, the Germen, the Stylus, and the Stigma” Barton 170–1; today the pistil with “ovary, style and stigma” Kew 90 | 5 | 109 |

| stamen [stamen, stamens] |

the male organ, Barton 108, “the filamentum, and th anther” Barton 158 | 240 [stamen, stamens] |

188 [stamen, stamens] |

The above definitions come primarily from:

- Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany: or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: 1803), www.google.com/books/edition/Elements_of_Botany_Or_Outlines_of_the_Na/Hk0aAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

When appropriate, additional modern definitions have been given for additional clarity or when today’s definition has changed. The modern definitions come from:

- Henk Beentje, The Kew Plant Glossary: An Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms (Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew Publishing, 2012).

- James G. Harris and Melinda Woolf Harris, Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary (Spring Lake, Utah: Spring Lake Publishing, 2009).

- James L. Reveal, on this website in Camas. See also by Reveal, Lewis as Botanist.

When not enclosed with quotation marks, the definition has been paraphrased from the given source.

In the two columns of word counts, every effort has been made to count only those instances where the intended meaning is the one given in the definition. Alternate forms—for example, claw, claws, clawed—have been counted. Latin equivalents have been excluded from the count except when they are used exclusively by the author. Their alternate spellings are enclosed in square brackets.

John Miller’s counts come from his two-volume translation:

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Sexual System, Of Linnaeus (London, 1779), books.google.com/books/about/An_Illustration_of_the_Sexual_System_Of.html?id=ak8-AAAAcAAJ.

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus (London, 1789), archive.org/details/illustrationofse02mill.

Notes

| ↑1 | 12 July 1804, The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed., 2:368. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Journals, 9:388. |

| ↑3 | Journals, 11:41. |

| ↑4 | Huron H. Smith, “Ethnobotany of the Forest Potawatomi Indians,” Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 7, no. 1 (9 May 1933): 109–10, www.survivorlibrary.com/library/ethnobotany-of-the-forest-indians.pdf. |

| ↑5 | Regarding alcohol on the expedition, see on this site Alcohol Rations. |

| ↑6 | William Clark, Journals, 3:261. |

| ↑7 | Shelly Katherene Kraft, “Recent Changes in the Ethnobotany of Standing Rock Indian Reservation”, M.A. Thesis (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, University of North Dakota University Commons, 1990), 39, commons.und.edu/theses/812/. |

| ↑8 | Melvin R. Gilmore, “Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, Number 33, 1919), 88, 89, as Padus nana, archive.org/details/usesofplantsbyin00gilm; Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 448. |

| ↑9 | John C. Hellson, “Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians,” National Museum of Man Mercury Series, no. 19 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974), 104, archive.org/details/ethnobotanyofbla0000hell. |

| ↑10 | Betty B. Derig and Margaret C. Fuller, Wild Berries of the West (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2001), 142. |

| ↑11 | Jeffrey A. Hart, “The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 4 (1981): 88. |

| ↑12 | Moerman, 445. |

| ↑13 | Hellson, 68. |

| ↑14 | Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1976), 88–89; Hart, “The Ethnobotany of the Northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana,” 35. |

| ↑15 | Hellson, 94, 104. |

| ↑16 | Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples, 89. |

| ↑17 | “Prunus virginiana,” Flora of North America, www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=242417061, accessed 20 February 2023. |

| ↑18 | Journals, 4:145–46. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.