“There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Meriwether Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.” He and his men must have seen it the previous autumn as they walked or rode horseback through the Bitterroot Mountains between Lost Trail Pass and Weippe Prairie, but this was the first time he had seen it in bloom, and the first time he could have compared it with the species he had known near his boyhood homes in the southern Appalachian Mountains (see Fig. 2).[1]Today Xerophyllum asphodeloides (L.) Nutt. is still found from New Jersey south to Alabama, and west to the Mississippi. It is classified as Rare in Georgia and Threatened in Tennessee. USDA-NRCS. … Continue reading

Figure 1

Beargrass blooms

© 9 July 2008 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Above: a clump of bear-grass with flower-tipped stalks rises from offshoots on a ridge in the Bitterroot Mountains along the Northern Nez Perce Trail.

Xerophyllum sp.

Eleven other plant species share the common name, bear-grass.[2]USDA, NRCS. 2004. The PLANTS Database, Version 3.5 http://www.npdc.usda.gov/ National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. The ten in the genus Nolina more closely resemble the Spanish bayonet, or Yucca glauca, (yucca) of the West. The eastern species, Xerophyllum asphodeloides (L.) Nutt. is locally known as turkeybeard. Where or when Lewis came to call it bear-grass is not known.[3]A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 178-179; 237. In any case, his association of the Rocky Mountain species with its eastern counterpart, even on an admittedly superficial level, is one more example of his native ability as a naturalist.

It is truly, as Lewis put it, a “luxouriant” evergreen, often growing in large, dense patches among lodgepole pine, subalpine fir and Engelmann spruce trees at elevations above 5,000 feet. It is found in the Northern Rockies, the Cascade and Coastal ranges, and the Sierras as far south as central California. Every few years, in June and July, it propagates offshoots from a creeping underground stem called a rhizome (RY-zome, from the Greek word for root). They give rise to sturdy green stalks that brighten the subalpine forest understory with large racemes (clusters) of small, delicately scented, creamy white flowers.[4]“Poaceae.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2004. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service (accessed 11 Feb. 2004). After the bloom is over, the offshoots die.

Figure 3

Beargrass Blooms

Photo by W.D. Bransford, Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, http://www.wildflower.org.

The shape of the inflorescence of Xeroplyllum tenax before its uppermost flowers are open may have been the inspiration for the Coastal Indians’ design of their rainproof hats (See Chinookan Woven Hats).

Grass-like Leaves

Bear “grass” is not a grass. True grasses belong to the Poaceae family (poh-AY-see-ee; from a Greek word for fodder), which is the most abundant flowering plant family on Earth, and a primary source of food, such as cereals, for humans and animals alike. All grasses have hollow stems divided by plugs or nodes from which two-part leaves grow in alternate arrays; their flowers are small and lack petals; and nearly all are pollinated by wind. The one thing Xerophyllum tenax has in common with any—though by no means all—of the nearly 650 genera and nearly 10,000 species of grasses, worldwide, is its long, slender leaf.[5]15 September 1805.

The leaves of Xerophyllum tenax are scabrous (rough) to the touch and finely serrate (saw-toothed on their edges) from tip to base, but they are as slippery in the opposite direction as they appear in the photo above. One can imagine that members of the Corps, probably shod in moccasins on both of their hikes across the Rockies, occasionally found their feet jerked out from under them on those dense clumps of leaves that hid the short, thick end of the rhizome. Even a horse can lose footing on them, and one wonders whether bear-grass might have caused those accidents the Corps’ livestock suffered while climbing up Wendover Ridge out of Lochsa River Canyon, injuring several animals and destroying Lewis’s portable desk.[6]Personal communication, 6 February 2004.

Indian Basket Grass

When applied to the gorgeous Xerophyllum (zero-PHIL-um; “dry leaf”) tenax (TEN-ax; “strong, tenacious”), the everyday name is, as someone once wrote, “a thorough rebuke to the unimaginativeness of the human mind.” A more descriptive name, a reminder of the plant’s centuries-long commercial value throughout northwestern America, is Indian basket grass.

Compared with its importance among Indian peoples of the Northwest, not only for hats but also for drinking cups and cooking vessels (using hot stones to boil water), Xerophyllum tenax is of little value today, commercially or otherwise. At most, some florists use the long-lasting evergreen leaves in flower arrangements. The craft of making or decorating baskets with them has not been entirely lost, but it is obviously of far less importance than it was when Lewis and Clark bought their new “hats of a conic figure.”

Biotic Community

Its place in the biotic community is still as viable as it has been for millions of years. Bears are said to eat the younger leaves, mountain goats reportedly feed on the leaves in winter, and moose tracks have been seen next to chomped-off leaves in early spring. Documentation of these anecdotes is hard to find, however. Elk are drawn to the flowers, stalks, and seed pods, and thus have lent Xerophyllum tenax another misleading common name—elk grass. birds have been observed stuffing themselves on its abundant seeds in autumn prior to their migrations. insects drink the flowers’ sweet nectar, and incidentally pollinate them. Birds come back in blossom-time to feed on the same insects.

Naturalist Sarah Walker adds more insights into this plant’s life story: “I’ve seen bird nests in and under the leaf clumps, and I’ve seen a neatly clipped arch-shaped entrance accessing the base of a leaf clump, where I believe a small animal made a home during winter, under the snow.” Regarding the flowers’ nectar, she writes, “I know it’s flavorful, because I’ve made bear-grass wine and it was delicious!”[7]Personal communication from Sarah Walker, 3 April 2004.

Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia

Drawing and engraving by William Hooker, from Frederick Pursh‘s Flora Americae Septentrionalis.[8]At lower left are two stamens (male organs of a flower); at right of the stamens is the top of an ovary (containing seeds) with three styles (stalks) tipped with stigmas (receptors for pollen). … Continue reading

Figure 6

Beargrass Inflorescence

Photo from The Lewis and Clark Herbarium;: Images of the Plants Seen or Collected by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 1804–1806, at http://www.life.umd.edu/emeritus/Reveal/pbio/LnC/fam3.html. Used by permission of The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia.

On average, depending on various factors, a beargrass inflorescence may contain between 50 and 250 flowers.

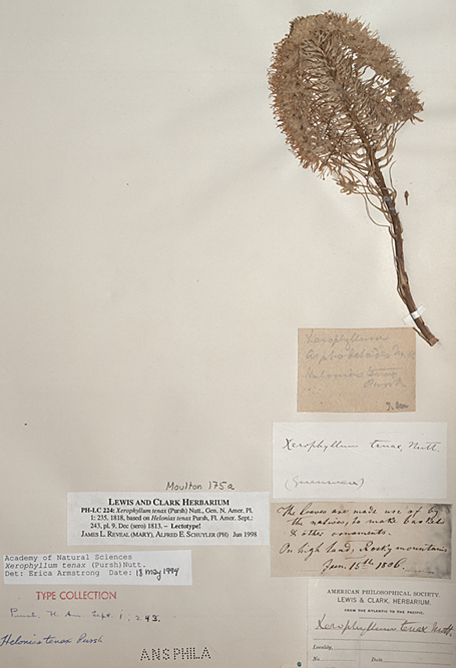

Lewis’s Dried Specimen

Many of the dried specimens Lewis and Clark gathered on their 1804-1806 expedition were used by the Saxon botanist Frederick Pursh to characterize those he felt were new to science. Herbarium specimens—dried and pressed specimens mounted on paper together with information as to their origins—serve as “vouchers,” or reference resources, for comparison with other specimens collected at a later time or in a different place.

When a new name is proposed today, a taxonomist declares a single specimen as the element the name is to be based upon. In the jargon of taxonomists, this single sheet is termed a holotype. The rules for naming new plants in Pursh’s time were less precise, and he only had to mention the collection, or collections, he used to describe his new plant. Again, in taxonomic jargon, each of the herbarium specimens is called a syntype.

Specimen Label

Xerophyllum asphodeloides

Nutt. Helonias tenax Pursh T.M.[9]The original element associated with a specimen is called the label. All other comments are annotations.

Frederick Pursh was the first scientist to study, describe and name this specimen, and for that reason he is called the “author”; his name appears immediately after the two scientific names he proposed for it. Since a common name may be used in various regions to refer to different plants—as in the case of “bear grass”–botanists and serious students of botany use the two-part official name (binomial) to refer to a plant. However, even the scientific name of a plant may change, as the taxonomic history of this plant proves.

Pursh placed this specimen in the genus Helonias,[10]Carolus Linneaus (1707–1778), the founder of botanical science, introduced the genus Helonias (hel-LO-nee-us; from the Greek word for “swamp”) into plant taxonomy … Continue reading which was a member of the Lily (Liliaceae, lil-ee-AY-see-ay) family.[11]Today this plant is classified in the family Melanthiaceae (MEL-anth-ee-AY-see-ay; the Bunchflower family, a subfamily of Liliaceae). The name he chose for its species designation, called the “specific epithet,” was tenax, meaning strong, or tenacious, in reference to the leaves, which are indeed tough and wiry. It is not known whether Lewis brought back any of the leaves (see Label 3). Pursh published his conclusions in his book, Flora Americae Septentrionalis—“Plants of North America”—in 1813–14 (see Label 7).

In 1818, another botanist, Thomas Nuttall, observed the specimen and concluded that it did not belong to the genus Helonias and proposed a new genus of the lily family, which he named Xerophyllum (zee-ro-PHIL-um), from the Greek xeros, dry, and phyllon, leaf. He proposed the specific epithet asphodeloides (ASS-fo-del-oides; Greek for resembling (oides) an asphodel, which was a species native to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Nuttall published his findings in his book, The Genera of North American Plants (1818).

This annotation was signed with the initials “T.M.” The handwriting has been identified as that of Thomas Meehan, which means this label was written in 1896.

—Joseph Mussulman, with assistance from James Reveal and Richard McCourt.

Annotation 1

Zerophyllum tenax Nutt.

(Greenman)

In 1897 Thomas Meehan sent some of Lewis’s specimens to J. M. Greenman, a botanist at Harvard University, for what scientists today refer to as “peer review”—confirmation or correction of his (Meehan’s) annotations. This is Greenman’s annotation; he should have put Pursh’s name in parenthesis before the abbreviation “Nutt.” to maintain Pursh’s status as the original author. Meehan added Greenman’s name.

Annotation 2

The leaves are made use of by

the natives, to make baskets

& other ornaments.On high land, Rocky mountains

June 15th, 1806

Botanist Frederick Pursh wrote this annotation in about 1807. He may have copied Lewis’s original label and then either lost or more likely discarded the original. Lewis may have recorded his collection of this specimen on 15 June 1806, the date the Corps camped on Eldorado Creek in the Bitterroot Mountains in prime beargrass habitat, but although he mentioned a number of trees and shrubs in his journal entry that day, he did not mention beargrass.

Annotation 3

American Philosophical society Lewis & Clark, Herbarium From the Atlantic to the Pacific

Xerophyllum tenax Nutt.

This annotation was on the specimen sheet that was stored at the American Philosophical Society from 1815 until 1896. It was Thomas Meehan who, in 1896, wrote on it the words Xerophyllum tenax Nutt. He should have included Pursh’s name in parentheses after tenax, to show that Pursh was the original author, and that Nuttall had revised Pursh’s taxonomy.

Annotation 4

Type Collection

Pursh, Fl. Am. Sept. 8:243Helonias tenax Pursh

The words “Type Collection” signify that this is the specimen used by Frederick Pursh, who named it and published the first description of the plant it represents. Helonias tenax is the name Pursh proposed in his book, Flora AmericaeSeptentrionalis—”Plants of North America”—which he published in late 1813. Concerning the the elements of his binomial, see Label 1.

The line “Pursh, Fl. Am. Sept. 8:243” was written by Francis W. Pennell (1886–1952), botanist, botanical historian and bibliographer at The Academy of Natural Sciences from 1921 until 1952.

It is not known who wrote the line “Helonias tenax Pursh.”

Annotation 5

Academy of Natural Sciences

Xerophyllum tenax (Pursh) Nutt.

Det.: Erica Armstrong Date 18 May 1994

Erica Armstrong was an intern at The Academy of Natural Sciences who reconfirmed the ownership and name of this specimen in 1994. The abbreviation det. stands for “determiner.”

Annotation 6

LEWIS AND CLARK HERBARIUM

PH-LC 224: Xerophyllum tenax (Pursh) Nutt., Gen. N. Amer. PL

1:235, 1818, based on Helonias tenax Pursh, Fl. Amer. Sept.:

243, pl. 9. Dec (sero) 1813.—Lectotype!

James L. Reveal (Mary), Alfred E. Schuyler (PH) Jun 1998

This annotation, the latest document in the history of the specimen, was written by two eminent American botanists: James L. Reveal, Professor Emeritus of Botany at the University of Maryland—thus “(MARY)”; and Alfred E. Schuyler, Curator Emeritus of Botany at The Academy of Natural Sciences—represented by the initials PH.

It attests that a new classification of this specimen was proposed by Thomas Nuttall in his book, The Genera of North American Plants, (1818), volume one, page 235, when he assigned Helonias (hel-LO-nee-us; from the Greek word for “swamp”) tenax to a new genus, Xerophyllum (zee-roh-PHIL-um; “dry leaf”). Further, it confirms that Nuttall’s new name was based on the name initially proposed by Frederick Pursh in his Flora Americae Septentrionalis, or “Plants of North America,” page 243 and plate 9, which was published in 1813 (see Label 1). The term sero indicates that the book was published so late in 1813 (December, actually) that its year of publication has been considered to be 1814.

Today, botanists working up the taxonomy of a new species would select a single herbarium specimen as the holotype, which would then serve as the basis for the original published description of the plant. The term lectotype (from Latin lego, to pick) is applied when an herbarium sheet has been chosen by others to stand for the type specimen when no holotype was designated by a name’s original author, in this case Pursh.

Above this label Earle Spamer, an archivist at The Academy of Natural Sciences, has added the note that a photograph of this specimen sheet is number 175a in Herbarium of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, Volume 12 (1999) of The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, edited by Gary E. Moulton.

The Herbarium

In 1815, William Clark gave all of Lewis’s botanical specimens to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, except some that Frederick Pursh had already taken back to Europe with him. There they lay in bundles, unremembered and unnoticed, until 1896, when botanist Thomas Meehan found them and secured permission to take them back to his institution, The Academy of Natural Sciences, to study and catalog them, and prepare them for proper storage. Some forty years later the specimens and the labels accumulated up to that time were transferred to new specimen sheets. They are still on deposit, or long-term loan, at the Academy—identified on this sheet by the perforated letters ANS PHILA. As custodian of the herbarium, it is the Academy’s responsibility to maintain and continue the collection’s provenance, or record of origin and identification.

Lewis brought back his specimens in folded sheets of blotter paper such as he had used to dry them. In the 1920s A. E. Fogg, an intern at the Academy, attached all 222 of the Lewis and Clark specimens now on deposit there to standard sheets such as the one above, measuring 11½” by 16¾”.

The Lectotype

In the case of Pursh’s Helonias tenax, formally proposed in his book Flora americae septentrionalis in December of 1813, he saw at least two herbarium specimens, both gathered by Lewis. In 1999, as may be seen on one of the labels attached to the specimen, this sheet was selected as the one herbarium sheet to represent Pursh’s concept of his Helonias tenax. This sheet is termed a lectotype, namely a type specimen selected by others to serve as the representative element.

Although devoid of its original color, fragrance and tactile qualities, this flat, brown, dried-out specimen supplies the scientist with important information that can be acquired in no other way: its morphology, the plant’s form and structure apart from its function in the biotic community and other identifying characteristics, such as DNA, which are now studied with the tools and methods of molecular biology.

The original label on a specimen sheet tells where and when the specimen was collected. Additional annotation labels provide other information such as who described and named it, where the original name and description were first published, and when and by whom new identifications, if any, were made by others.

Notes

| ↑1 | Today Xerophyllum asphodeloides (L.) Nutt. is still found from New Jersey south to Alabama, and west to the Mississippi. It is classified as Rare in Georgia and Threatened in Tennessee. USDA-NRCS. 2004. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov/plants). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. The specific epithet asphodeloides means “resembling an asphodel.” C. Leo Hitchcock and Arthur Cronquist, Flora of the Pacific Northwest (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 696. In Greek poetry and mythology, the flower of the asphodel, a native of the Mediterranean region, was associated with Persephone, wife of Pluto and queen of the realm of the dead. The plant was said to grow in Hades, where its roots were food for dead souls. In early English and French poetry, asphodel was a synonym for daffodil and narcissus. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | USDA, NRCS. 2004. The PLANTS Database, Version 3.5 http://www.npdc.usda.gov/ National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA. |

| ↑3 | A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 178-179; 237. |

| ↑4 | “Poaceae.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2004. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service (accessed 11 Feb. 2004). |

| ↑5 | 15 September 1805. |

| ↑6 | Personal communication, 6 February 2004. |

| ↑7 | Personal communication from Sarah Walker, 3 April 2004. |

| ↑8 | At lower left are two stamens (male organs of a flower); at right of the stamens is the top of an ovary (containing seeds) with three styles (stalks) tipped with stigmas (receptors for pollen). Wrapped around the inflorescence (the raceme of flowers) is a single leaf-blade. At lower right is a single flower on a pedicel (flower-stalk) which grows from the axil (base) of a bract (the little “leaf”). |

| ↑9 | The original element associated with a specimen is called the label. All other comments are annotations. |

| ↑10 | Carolus Linneaus (1707–1778), the founder of botanical science, introduced the genus Helonias (hel-LO-nee-us; from the Greek word for “swamp”) into plant taxonomy (“classification”) in 1753. A North American species is H. bullata (bul-LAY-tuh; referring to the projections resembling unbroken blisters on its flowers), once native to the East Coast from Delaware to South Carolina and Georgia. Commonly called “swamp pink,” it has been on the national list of threatened species since 1988. |

| ↑11 | Today this plant is classified in the family Melanthiaceae (MEL-anth-ee-AY-see-ay; the Bunchflower family, a subfamily of Liliaceae). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.