“. . . the more than two hundred specimens that reached Philadelphia, from the activities of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, signified the richness of the flora of the Pacific Northwest and particularly the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Western Montana.”

Lewis’s Plant Collection

Even on the toughest days of the expedition, Lewis somehow found time to observe plants along the way. However, his major periods of systematic work evidently were at Fort Mandan, Fort Clatsop, and Long Camp.

Lewis as Botanist

"No regular botanist"

by James L. Reveal

This interview with botany Professor James Reveal recorded at Packer Meadow near Lolo Pass analyzes the botany of Lewis.

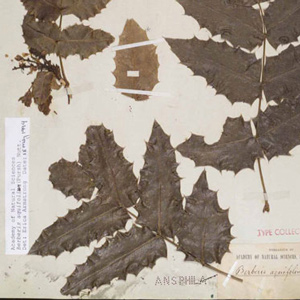

The Donation Book

Catalog of specimens

by Earle E. Spamer, Richard M. McCourt

The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled for the Lewis and Clark materials received in November 1805. The entries were sequentially numbered by John Vaughan of the APS in Philadelphia.

Jerusalem Artichokes

Helianthus tuberosus

by Joseph A. Mussulman, Kristopher K. Townsend

The French explorer Samuel de Champlain found the vegetable growing in Indian gardens along the Saint Lawrence seaway and carried specimens of it back to France in 1603, where its root soon became a staple food for humans.

Bearberry

Kinnikinnick, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark sometimes called it kinnikinnick, sometimes sacacommis. At Fort Clatsop on 29 January 1806, he described this useful plant.

Beargrass

Xerophyllum tenax

by James L. Reveal, Richard M. McCourt, Sarah Walker

There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.”

Biscuitroots

Nature's grateful vegetable

by Jack Nisbet

Columbia plateau biscuitroots: “one of the grateful vegetables” by naturalist Jack Nisbet. An Indian food source for thousands of years.

The Bitterroot Plant

Lewisia rediviva

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Flathead Salish, Kutenai, Shoshoni, and Nez Perce people all regard the bitterroot with solemn reverence. No other root may be harvested until the elder women of the tribe have conducted the annual First Roots ceremony.

Indian Breadroot

Pediomelum esculentum

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The day Sacagawea gathered Indian breadroot, Lewis wrote a detailed ethnobotanical description. The specimen he prepared a year prior is now used as the primary identifier of the species.

Buffaloberry

Shepherdia argentea

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Lewis collected buffaloberry specimens which were new to science and Clark had them in a delightful tart. Native Americans had been eating the bright red berries for generations.

Camas

Camassia quamash

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

William Clark, pushing on in advance of the hungry men of the Corps, came upon two adjacent Indian villages totaling about 30 lodges on Weippe Prairie. They gave him and his six hunters “roots in different States, Some round and much like an onion which they call quamash.”

Wild Cherries

by Kristopher K. Townsend

As the expedition moved across the Northern American continent, Lewis took particular notice of the changes he saw in the wild cherries. For a deeper dive into the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s encounters with wild cherries, see these four articles.

Cous

Lomatium cous

by Joseph A. Mussulman

William Clark first mentioned the root cous on 1 November 1805, saying that native people living near the future Bonneville Dam site traded beads to obtain it from people up the Columbia River. To Clark, it was “cha-pel-el bread.”

Echinacea

Prairie coneflower, E. angustifolia

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Justified by the ethnobotanical record, the captains went to unusual lengths to preserve and document echinacea. Most—if not all—the Tribal Nations encountered along the Missouri River used the plant to treat snakebites in the manner described by the two captains.

Elkhorn

Clarkia pulchella

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

The plant’s common names include elkhorn, ragged robin, pink fairy, and deerhorn. In the spring of 1807 Lewis turned over his plant specimens to Frederick Pursh, who gave this flower the scientific name Clarkia pulchella

Wild Ginger

Asarum canadense

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis reported that a specimen of this plant “was taken the 1st of June at the mouth of the Osage River; it is known in this country by the name of the wild ginger.”

Oregon Grapes

Berberis aquifolium

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In his journal for 12 February 1806, Lewis described the plant that now goes by the name Berberis aquifolium, which he had first noticed in the vicinity of the Cascades of the Columbia River, about 145 miles from the ocean.

Mixed-grass Prairie

On 8 July 1806, Lewis descended from the Rocky Mountains and entered the “Plains of the Missouri,” a prairie type that extended as far as North Dakota.

Sweet Grass

Hierochloe odorata

by Joseph A. Mussulman

For thousands of years sweet grass has been used as incense in spiritual and religious ceremonies, as a personal perfume, and braided into necklaces and bracelets for wearing as amulets to ward off illness and injury.

Lady’s Slipper

Cypripedium montanum

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Above Montana’s Lolo Creek, Lewis noticed a flower: “in shape and appearance like ours”—in Virginia, of course—”only that the corolla is white, marked with small veigns of pale red longitudinally on the inner side.”

Glacier Lilies

Erythronium grandiflorum

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Because it appears in the Rockies at the edges of receding snowbanks it has also earned the name glacier lily. Lewis’s specimen, collected 15 June 1806 on the Clearwater River, was the one used by Pursh to describe the species.

Prickly Pears

One of nature's greatest pests

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“The prickly pear is now in full blume,” he wrote on a mild early-summer day in 1805, “and forms one of the beauties as well as the greatest pests of the plains.”

Wild Roses

Rosa woodsii

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Meriwether Lewis was sufficiently familiar with the genus back home to recognize the new species he termed the “small rose of the prairies,” which he found on 5 September 1804, in present-day Nebraska near the mouth of the Niobrara River.

Serviceberry

Amelanchier alnifolia

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Everybody liked the abundant serviceberry fruit—the Lemhi Shoshones were living on them, the enlisted men “regaled themselves,” and Lewis was the first to collect a specimen for science.

The Snowberry

Symphoricarpos albus

by Joseph A. Mussulman

13 August 1805 near Lemhi Pass, Lewis wrote that he noticed “a species of honeysuckle much in it’s growth and leaf like the small honeysuckle of the Missouri.” He had discovered a plant that was new to the scientific community—the snowberry.

Sunflowers

Helianthus annuus

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The common sunflower as a staple food among the Mandans and Lemhi Shoshones did not escape the attention of the journalists. Includes two traditional Hidatsa recipes.

Native Tobacco

Nicotiana quadrivalvis

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis mentioned two species of tobacco, possibly Nicotiana quadrivalvis and N. rustica—a Mexican species called Aztec tobacco—that the Arikara cultivated.

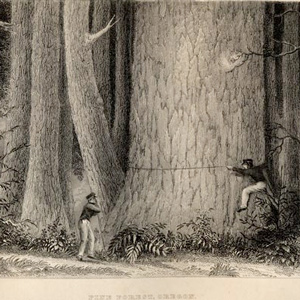

Trees

Previous explorers and trading ships came back from the Northwest Coast with reports of forests thick with gigantic spruce, cedar, and firs. What would Lewis report of this natural resource? And what of the cottonwoods along the drainages everywhere else?

Edible Valerian

Valeriana edulis

by Joseph A. Mussulman

One of the roots obtained by George Drouillard on 21 August 1805 may have been a species of valerian (vuh-LEHR-ee-an), such as Valeriana edulis (vuh-leh-ree-AYE-nuh ed-YOU-lis), or edible valerian.

Wapato

Sagittaria latifolia

by Barbara Fifer

If this plant was what Sacagawea was referring to when she told Clark she favored spending the winter anyplace where there was “plenty of Potas,” it may be that some of the men had recognized it as “duck potato” or “Indian potato.”

Weeds on the Lolo Motorway

Modern invasives

by Sarah Walker

During the summer of 2003 a weed inventory team from the University of Idaho searched the Lolo Motorway for weeds. They saw spotted knapweed four times, orange hawkweed twice, yellow hawkweed twice, henbane once, and goatweed 28 times: 37 widely-scattered weed sightings in about 50 miles.

Western Spring Beauty

Claytonia lanceolata

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On 25 June 1806, on the branch of Hungery Creek where they “nooned it,” Sacagawea brought the captains “a parcel of roots” that Lewis immediately recognized as the kind Drouillard had given him ten months earlier.

Yucca

Soapweed, Yucca glauca

by James L. Reveal, Joseph A. Mussulman

None of the expedition’s journalists made any note of yucca, although in writing of Lemhi-Shoshone Indian dress, Meriwether Lewis mentioned “a small cord of the silk-grass” which at least one scholar has interpreted as referring to the yucca.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.