If we had a keen vision of all that is ordinary

in human life, it would be like hearing

the grass grow or the squirrel’s heart beat,

and we should die of that roar which is

the other side of silence.

Columbian Ground Squirrel

Spermophilus columbianus Ord (1815)[1]Spermophilus (sper-mo-phil-us) is Latin for “seed lover”; columbianus (co-lum-be-an-us) refers to the Columbia River basin. George Ord (1781-1866), whose most important work was done in … Continue reading

© 2007 by WikiCommons user Jayjayp who has licensed it under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Erect on its hind legs, its forepaws poised in the characteristic pose accompanying its recognition of a potential threat—possibly the photographer in this instance—a specimen of mature squirrelhood, probably a female, alerts its kin with an insistent three-tweet alarm.

George Ord (1781-1866) was responsible for publishing the first formal description of this species—drawn verbatim from Lewis’s journal as condensed by Nicholas Biddle—in 1815, giving it the common name “Louisiana marmot,” and the official binomial Arctomys columbianus. Most of the early naturalists like Ord used the generic epithet Arctomys (ARC-toh-meess; literally “bear-mouse”) as a synonym for Marmota (mar-MOH-tuh, “mountain-rat”). In 1825 the prominent French zoologist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) proposed the generic name Spermophilus (spur-MAH-phil-us, “seed-lover”) for all ground squirrels, but it didn’t become official until many years later.[2]Arthur H. Howell, “Revision of the North American Ground Squirrels, with a Classification of the North American Sciuridae,” North American Fauna, No. 56, United States Department of … Continue reading

Labiche’s Specimens

Back in the closing decades of the so-called “Little Ice Age” (c.1550 CE to c. 1850 CE), spring began some two to three weeks later than it does in the second decade of the 21st century, and annual runoff of mountain snow was still typically slow. So, on the 23 May 1806, high water still prevented the Corps’ hunters from getting up into deer country on the north side of the Clearwater River above Collins’ Creek (later Idaho’s Lolo Creek). But that didn’t impede the captains’ search for new natural history specimens. During their forced suspension from travel Lewis wrote some descriptions that were longer and more thoughtfully detailed than most of those written among the distractions of daily moves. Lewis continued his study of the grizzly bear, reaching the conclusion that there no subspecies after all, but merely color variations among the few otherwise indistinguishable varieties. They examined beargrass, and elkhorn, and cous. They observed and described the pigmy horned lizard, the great gray owl, the western tanager . . . and the Columbian ground squirrel.

Lewis himself might have stumbled upon that particular squirrel sooner or later, but it was Private François Labiche who saw it first. The company was in need of some fresh red meat, so on the morning of 23 May, the captains sent six hunters into the woods on the north side of the Clearwater River to see what they could find. All six returned at one in the afternoon with no fresh meat beyond a few blue grouse.[3]The six hunters were John Collins, John Colter, Pierre Cruzatte, François Labiche, Jean-Baptiste LePage, and George Shannon.

Two of those hunters, however were commendable for their obedience to the standing order for hunters to be on the lookout for new species. One man, who was not identified, brought in “a large hooting owl which differ[s] from those of the atlantic States.” It was the great gray owl (Strix nebulosai), previously unknown to science.[4]Lewis wrote the first description of it in considerable detail on 28 May 1806. It is not the largest owl. That reputation belongs to the Great Horned and the Snowy owl. Lewis, who wrote the most detailed description of it, called it a “large hooting Owl.” Its overall color, he judged, was “properly termed a dark iron grey.” Its head had “a flat appearance being broadest before and behind,” and was one foot 10 inches in circumference.

In addition, according to Clark, Labiche handed over “a whisteling squerel which he had killed on it’s hole in the high plains.” Labiche’s discovery was a testament to his sharp eye and quick mind; thus far they had all seen at least a half-dozen different squirrels. Since setting up Long Camp on 14 May 1806 they had shot several familiar species, such as the diminutive one later identified as Richardson’s red squirrel, but this one appeared to Labiche to be different. After a thorough inspection, end to end, inside and out, including the contents of its stomach, Clark confirmed Labiche’s judgment: “this squerel differs from those on the Missouri in their Colour, Size, food, and the length of ta[i]l and from those found near the falls of Columbia.”

Clark’s and Lewis’s Descriptions

Labiche’s discovery and Clark’s terse confirmation took place while the Corps was bivouaced at Camp Chopunnish (as Olin D. Wheeler dubbed it in 1904. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.), across the Clearwater River from the regular winter home of the Nez Perce, near which the town of Kamiah was founded in 1896. Four days after Labiche’s discovery, Meriwether Lewis penned one of his longest (663 words) and most meticulous descriptions of any small mammal. Nicholas Biddle, whom Clark had engaged to edit his and Lewis’s journals for publication, trimmed down Lewis’s discussion to 505 words. Nevertheless it is the longest of the descriptions of the expedition’s five new squirrels, the others being the “large gray squirrel” (Sciurus fossor (“ground squirrel”)[5]The name S. fossor was published in 1845 by Titian Ramsay Peale, the author of the Zoology of the Wilkes expedition (1838-42). The species was renamed S. heermanni in 1852 by John Eatton Le Conte … Continue reading Lewis described it as “much superior in size to the common gray squirrel, and resmbles in form, color, and size the fox-squirrel of the Atlantic States . . . .” Lewis continues:

There is also a species of squirrel, evidently distinct, which we have denominated the burrowing-squirrel. He inhabits these plains, and somewhat resembles those found on the Missouri. He measures one foot and five inches in length, of which the tail comprises two and a half inches only. The neck and legs are short; the ears are likewise short; obtusely pointed, and lie close to the head, with the aperture larger than will generally be found among burrowing animals. The eyes are of a moderate size; the pupil is black, and the iris of a dark sooty brown; the whiskers are full, long, and black. The teeth, and, indeed, the whole contour, resemble those of the squirrel:

Each foot has five toes [claws]; the two inner ones of the fore feet are remarkably short, and equipped with blunt nails; the remaining toes on the front feet are long, black, slightly curved, and sharply pointed.

The hair of the tail is thickly inserted on the sides only, which gives it a flat appearance, and a long oval form; the tips of the hairs forming the outer edges of the tail are white, the other extremity of a fox red; the under part of the tail resembles an iron gray; the upper is of a reddish brown; the lower part of the jaws, the under part of the neck, legs and feet, from the body and belly downward, are of a light brick red; the nose and eyes are of a darker shade of the same colour; the upper part of the head, neck, and body, are of a curious brown-gray, with a slight tinge of brick red; the longer hairs of these parts are of a reddish-white color, at their extremities, and falling together give this animal a speckled appearance.

These animals form in large companies, like those on the Missouri, occupying with their burrows sometimes 200 acres of land; the burrows are separate, and each possesses, perhaps, ten or twelve of these inhabitants. There is a little mound in front of the hole, formed of the earth thrown out of the burrow, and frequently there are three or four distinct holes forming one burrow, with these entrances around the base of the little mound. These mounds, sometimes about two feet in height and four in diameter, are occupied as watch-towers by the inhabitants of these little communities. The squirrels, one or more, are irregularly distributed on the tract they thus occupy, at the distance of ten, twenty, or sometimes from thirty to forty yards.

When any one approaches they make a shrill whistling sound, somewhat resembling tweet, tweet, tweet—the signal for their party to take the alarm and retire into their intrenchments. They feed on the roots of grass, etc.[6]Meriwether Lewis and others, History of the expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the sources of the Missouri: thence across the Rocky mountains and down the river Columbia to … Continue reading

Scientific Responses

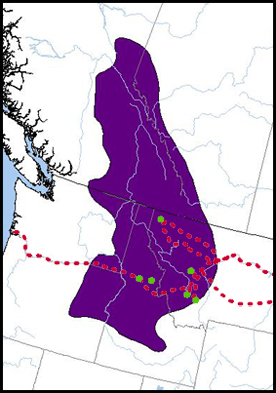

The purple figure encompasses the area in which Columbian ground squirrel colonies may be found. The dotted red line represents the Corps of Discovery’s travel route through the west. The green dots indicate approximate locations where they encountered the species. Columbian ground squirrels are native to southeastern British Columbia and southwestern Alberta, eastern Oregon and Washington, northern Idaho and western Montana.

Naturalist George Ord (1791-1866) interpreted Lewis-Biddle’s two comparisons of the Columbian ground squirrel with “those found on the Missouri” as a reference to the prairie dog, but Lewis emphasized they were “distinct species.” Coues supposed that the comparison might have been with Richardson’s small gray ground squirrel (today, Spermophilus richardsonii), which Clark may have seen on 9 April 1805, two days after the Corps left Fort Mandan.[7]See Moulton, Journals, 4:15, 18n. Biddle skipped over Lewis’s report that one of the specimens he examined “had in his mouth two small bulbs of a speceis of grass, which resemble very much what is sometimes called the grassnut,” a detail that might have been considered important by a systematic zoologist.[8]Possibly the yellow nutsedge, Cyperus esculentus Linnæus (sip-per-us es-cue-len-tus), or some other species of Cyperus. “Grassnut” may have been a common name locally. Biddle also omitted the original description of “the outer and inner toes of the hind feet,” in which Lewis explained that they “are not short, yet they are by no means as long as the three toes in the center of the foot, which are remarkably long, but the nails are not as long as those of the fore feet, though the same form and color.” That elision was not inconsequen-tial, for “that rattle-headed genius” (Coues’ phrase) Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz evidently had seen, or even had in hand, one of the several skins of the species that Lewis brought back “with the heads feet and legs entire” for Peale’s Museum. Observing the same features of the hind feet as Lewis had, but which Biddle had omitted, Rafinesque introduced it as a new genus and a new species, with a tersely descriptive official name: Anisonyx brachiura—”short-tail unequal-claw.”[9]“Descriptions of seven new genera of North American Quadrupeds,” in Rafinesque’s regular column, “Museum of Natural Sciences,” The American Monthly Magazine and Critical … Continue reading

For 91 years, until the publication in 1905 of Reuben Gold Thwaites’s annotated transcription of all of the original journals then known to exist, Biddle’s paraphrase served as the basis of a number of published identifications and descriptions of the Columbian ground squirrel. It bore at least ten new formal and informal names, proposed by leading zoologists and systematists. The changing of names and descriptions is normal throughout the life sciences, as new facts are revealed, and new interpretations of old facts are promugated. Taken together they reflected an increase in the number of serious zoologists who were studying Rodentia, the progress toward the realization that rodents comprise 40 percent of all known quadrupeds in the world, and that in North America alone there are 267 species of 49 different genera in the family Sciuridae.

Great Columbia Plateau

The phrase “these plains” in the second sentence of Lewis’s description may be somewhat misleading, in view of the fact that the discovery was made not on plains as we commonly think of them, but in a small, moist, grassy meadow among the otherwise dense forest of the Bitterroot Mountains. George Ord, who published the first scientific taxonomy of the species in 1815, assigned it the specific epithet columbianus, thereby compounding the confusion: Lewis didn’t find it on the Columbia River.

From Sherman Peak in the Bitterroot Mountains in September 1805 the captains glimpsed the eastern margin of the vast treeless basin that soon came to be known as the Great Columbia Plain or Plateau, and they intuited its significance from that very moment—they had found their way out of the mountains, and were summoned by wide-open spaces. On the 18th Clark was the first to see it. He had gone on ahead with several hunters in the hope of finding game to send back to the main party, when he reached a “Steep Knob” at the end of a “Dividg ridge” from which he “beheld a wide and extencive vallie in a West S W Direction.” Lewis saw it on the 19th when the ridge he was following terminated on Sherman Peak,

and we to our inexpressable joy discovered a large tract of Prairie country lying to the S. W. and widening as it appeared to extend to the W. through that plain the Indian informed us that the Columbia river, in which we were in surch run. this plain appeared to be about 60 Miles distant, but our guide assured us that we should reach it’s borders tomorrow

Obviously, and comfortingly, the same Nez Perce warrior who had offered to guide them to his people, was intimately acquainted with the region. Moreover, when the Corps reached The Dalles on 16-17 April 1806, en route home, they could distinctly tell from its drier, purer air that they had reached the western border of those Great Plains of the Columbia. The rich verdure of grass and herbs exhibited “a beautifull seen particularly pleasing after having been so long imprisoned in mountains and those almost impenetrably thick forrests of the seacoast.” So much for the Great Plains of the Columbia or, as they called it on their map of 1810, the “Columbia Valley,” greatly extending its northern and southern boundaries, which they never saw.[10]Donald W. Meinig, The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968), 45-47.

But the species of squirrel that Lewis and Clark found in the vicinity of The Dalles was observed at the same place in 1818 by George Ord, who named it Sciurus griseus—the western gray squirrel, whereas the Spermophilus columbianus was more at home in small, moist, high-elevation meadows or “holes,” which Lewis and Clark often more appropriately called “glades.”[11]Elijah Harry Criswell, Lewis Clark, Linguistic Pioneers (Columbia: University of Missouri, 1940), 42. Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (Philadelphia, 1806).

More Encounters

Eighteen days after Labiche returned to camp with the new rodent in his bag, the entire Corps of Discovery left Long Camp (elevation 1700 ft. MSL), where they had been bivouaced since 14 May 1806, to climb up to Weippe Prairie, at an elevation of a little over 3000 ft. MSL, where they camped near another colony of “burrowing squirrels.” They killed several, and both captains “eat of them and found them quite as tender and well flavored as our [eastern grey squirrel.” Early in July, as Lewis and his detachment headed back toward the Great Falls of the Missouri, following the Indian road that paralleled the Big Blackfoot River, one of the easternmost sources of the Columbia, they observed “great Number[s] of the burrowing squirrls” at between 4000 and 4300 ft. MSL along the “prarie of the knobs.” On the next day they saw still more “burrowing Squirels of the Species common to the Columbian plains.” At Camp Disappointment (elevation 3600 ft. MSL) on 23 July 1806 he observed “a number of the whistleing squirrel of the speceis common to the plains and country watered by the Columbia river,” adding, “this is the first instance in which I have found this squirrel in the plains of the Missouri.” Clark, after leaving Travelers’ Rest for Camp Fortunate on 3 July 1806, observed “the burring Squirel of the Species Common about the quawmarsh flats West of the Rocky Mountains.” The Bitterroot (his Clark’s) River that he was following is one of the easternmost sources of the Columbia.

It is understandable that Lewis and Clark had some difficulty keeping their descriptions of rodents clearly separate from one another, and that their designations were often misled, and misleading—calling the chipmunk a ground squirrel, for example. It is similarly remarkable that they actually made a number of verifiable discoveries of species that were previously unknown to naturalists—the western gray squirrel, the chickaree or western red squirrel, the prairie dog, the bushy-tailed woodrat, and the mountain beaver.

Lewis’s description is accurate enough, considering that his scope of exploration was mostly linear—he seldom ranged very far afield from the watercourses that were his highways—and he was driven by the need to keep moving toward his destination and ultimately toward home. Therefore most of his discoveries were serendipitous, and he had no grounds, nor any reason, for guessing what he might have missed. It would take many years for other explorers—more and more of them with ever-narrower scopes of inquiry—to add to his results the dozen or more species of North American ground squirrels that he did not find. However, his discoveries provided a baseline for his followers to build on. The dimensions of the specimen he studied are characteristic of the species; it is now said that its total length ranges between 12.9 and 14.8 inches, including a tail of from 3 to 5 inches. His meticulous, almost affectionate description of this squirrel’s colors is a testament to his capacity for noticing subtle details. However, we can only speculate on how he could have acquired general knowledge such as the area of the land occupied by a squirrel “ascociation,” and the number of occupants per burrow. Perhaps one or more of the hunters conveyed their observations to him, although we are never told that. Otherwise, the answers may have come from close observations on his part, perhaps combined with patient questioning of cooperative Nez Perce informants carried on across the linguistic divide by the eloquent hands of George Drouillard, the Plains Sign Language expert.

A full-grown Columbian ground squirrel may weigh nearly 30 ounces in the fall, but in May, just having emerged, hungry, from hibernation, Lewis’s specimens probably weren’t very filling to those diners. They may be tasty and they may be cute, even handsome by certain standards, but today ground squirrels such as Spermophilus columbianus Ord are unadulterated nuisances. In town they puncture sprinkling systems and eat vegetable gardens from the roots up; on a farm their mounds can damage farm equipment and their burrows can cripple cattle if they step in the holes.

Notes

| ↑1 | Spermophilus (sper-mo-phil-us) is Latin for “seed lover”; columbianus (co-lum-be-an-us) refers to the Columbia River basin. George Ord (1781-1866), whose most important work was done in the field of ornithology, was among the more prominent naturalists of his generation. He was responsible for writing the first scientific taxonomies of several mammalian specimens observed by Lewis and Clark, including the grizzly bear, the pronghorn, and the Columbian ground squirrel. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Arthur H. Howell, “Revision of the North American Ground Squirrels, with a Classification of the North American Sciuridae,” North American Fauna, No. 56, United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Biological Survey (Washington, D.C., April 1938), 53. Cuvier and others, Synopsis of the Species of the Class Mammalia, 12 vols. (London, George B. Whittaker, 1827), 5:243-48. Internet Archive. |

| ↑3 | The six hunters were John Collins, John Colter, Pierre Cruzatte, François Labiche, Jean-Baptiste LePage, and George Shannon. |

| ↑4 | Lewis wrote the first description of it in considerable detail on 28 May 1806. It is not the largest owl. That reputation belongs to the Great Horned and the Snowy owl. |

| ↑5 | The name S. fossor was published in 1845 by Titian Ramsay Peale, the author of the Zoology of the Wilkes expedition (1838-42). The species was renamed S. heermanni in 1852 by John Eatton Le Conte (1774-1860). Both authors had overlooked the fact that George Ord had published the name Sciurus griseus (“gray squirrel”) in the Journal de Physique in 1818. |

| ↑6 | Meriwether Lewis and others, History of the expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the sources of the Missouri: thence across the Rocky mountains and down the river Columbia to the Pacific ocean; performed during the years 1804-5-6; by order of the government of the United States, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814), 2:173-74. |

| ↑7 | See Moulton, Journals, 4:15, 18n. |

| ↑8 | Possibly the yellow nutsedge, Cyperus esculentus Linnæus (sip-per-us es-cue-len-tus), or some other species of Cyperus. “Grassnut” may have been a common name locally. |

| ↑9 | “Descriptions of seven new genera of North American Quadrupeds,” in Rafinesque’s regular column, “Museum of Natural Sciences,” The American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review, vol. 2, no. 1 (November 1817), 45. American Periodicals Series Online. |

| ↑10 | Donald W. Meinig, The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968), 45-47. |

| ↑11 | Elijah Harry Criswell, Lewis Clark, Linguistic Pioneers (Columbia: University of Missouri, 1940), 42. Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (Philadelphia, 1806). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.