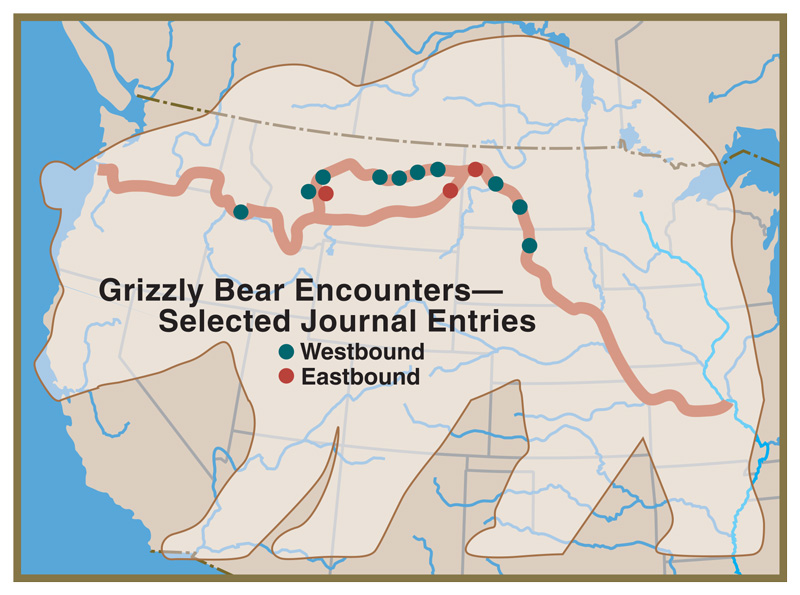

Click a spot on the map to read a journal entry for that location on the trail.

7 Oct 1804: ‘Verry large’

On 7 October 1804, at the Moreau River, about 15 river-miles below present Mobridge, South Dakota, the men noticed the first evidence of the presence of a grizzly. Clark wrote:

at the mouth of this river we Saw the Tracks of White bear which was verry large.

Between this point and their last encounter with a grizzly on 6 August 1806, near today’s Williston, North Dakota, the total number sighted cannot be known. Forty-three were definitely killed, and an unknown number were wounded.

At his Fort Clatsop desk, on 16 February 1806, Meriwether Lewis summarized what he had learned about the grizzly’s habitats:

The brown white or grizly bear are found in the rocky mountains in the timbered parts of it or Westerly side but rarely; they are more common below the rocky Mountain on the borders of the plains where there are copses of brush and underwood near the watercouses. they are by no means as plenty on this [the western] side of the rocky mountains as on the other, nor do I believe that they are found atall in the woody country, which borders this coast as far in the interior as the range of mountains which, pass the Columbia (river) between the Great Falls and rapids of that river.

20 Oct 1804: Standoff

On 20 October 1804, near the Heart River at today’s Mandan, North Dakota, men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition saw their first sign of the grizzly bear. The result was anticlimactic.

Clark wrote:

Our hunters killed 10 Deer & a Goat today and wounded a white Bear I saw Several fresh track of those animals which is 3 times as large as a man’s track.

Lewis added a few details:

Peter Crusat this day shot at a white bear he wounded him, but being alarmed at the formidable appearance of the bear he left his tomahalk and gun; but shortly after returned and found that the bear had taken the oposite rout.

It just wasn’t Pierre Cruzatte‘s day. “Soon after,” continued Lewis, “he shot a buffaloe cow broke her thy, the cow pursued him he concealed himself in a small raviene.”

13 Apr 1805: Formidable Account

On 13 April 1805, at the Little Missouri River, Lewis wrote expectantly:

we saw . . . many tracks of the white bear of enormous size, along the river shore and about the carcases of the Buffaloe, on which I presume they feed. we have not as yet seen one of these anamals, tho’ their tracks are so abundant and recent. the men as well as ourselves are anxious to meet one of these bear.

Lewis’s pulse must have raced as he continued:

the Indians give a very formidable account of the strength and ferocity of this anamal, which they never dare to attack but in parties of six, eight or ten persons; and are even then frequently defeated with the loss of one or more of their party. the savages attack this anamal with their bows and arrows and the indifferent guns with which the traders furnish them, with these they shoot with such uncertainty and at so short a distance . . . that they frequently mis their aim & fall a sacrefice to the bear. . . . this anamall is said more frequently to attack a man on meeting with him, than to flee from him. When the Indians are about to go in quest of the white bear, previous to their departure, they paint themselves and perform all those supersticious rights commonly observed when they are about to make war uppon a neighbouring nation.

5 May 1805: A ‘Tremendious Looking Anamal’

On 5 May 1805, in the vicinity of Wolf Point, Montana, Lewis wrote:

Capt. Clark & Drewyer killed the largest brown bear this evening which we have yet seen. it was a most tremendious looking anamal, and extreemly hard to kill notwithstanding he had five balls through his lungs and five others in various parts he swam more than half the distance across the river to a sandbar & it was at least twenty minutes before he died; he did not attempt to attact, but fled and made the most tremendous roaring from the moment he was shot.

Lewis took measurements:

We had no means of weighing this monster; Capt. Clark thought he would weigh 500 lbs. for my own part I think the estimate to small by 100 lbs. He measured 8 Feet 7-1/2 Inches from nose to extremity of the hind feet; 5 F. 10-1/2 Inch arround the breast, 1 F. 11 I[nches]. arround the middle of the arm, & 3 F. 11 I. arround the neck; his tallons which were five in number on each foot were 4-3/8 Inches in length.

As to weight, they were both close. Today the average weight of an adult male grizzly is between 350 and 700 pounds. The heaviest on record weighed 1,496 pounds. But as naturalist Adolph Murie once remarked, “a bear a long distance from a scale always weighs more.”

6 May 1805: ‘Curiossity Satisfied’

On 6 May 1805, near the Milk River, in northeastern Montana, Meriwether Lewis revised his opinion of grizzlies once again. He referred to them as “gentlemen,” that word denoting, in Lewis’s lexicon of manners, a landowner. And those animals clearly were the undisputed sovereigns of the river bottoms.

I find that the curiossity of our party is pretty well satisfied with rispect to this anamal, the formidable appearance of the male bear killed on the 5th added to the difficulty with which they die when even shot through the vital parts, has staggered the resolution of several of them, others however seem keen for action with the bear; I expect these gentlemen will give us some amusement sho[r]tly as they soon begin now to coppolate.

Lewis must have learned of the bears’ breeding schedule from the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians during the winter of 1804-1805, which is testimony both to the depth of his communication with residents along his route, and to the meticulous care he exercised in the collection of scientific data.

Indeed, the mating period extends from May to July. After a gestation period of 235 days, cubs are born in the hibernation dens in midwinter.

11 May 1805: Gentlemen!

On 11 May 1805, a few miles upstream from the mouth of the Milk River, one member of the party had a hairbreadth escape from death. Lewis recorded the details:

About 5 P.M. my attention was struck by one of the Party running at a distance toward us and making signs and hollowing as if in distress, I ordered the perogues to put too, and waited until he arrived; I found that it was Bratton the man with the soar hand whom I had permitted to walk on shore, he arrived so much out of breath that it was several minutes before he could tell what had happened. . . .

Private William Bratton, who was not among their best hunters:

. . . had shot a brown bear which immediately turned on him and pursued him a considerable distance but he had wounded it so badly that it could not overtake him; I immediately turned out with seven of the party in quest of this monster, we at length found his trale and persued him about a mile by the blood through very thick brush of rosbushes and the large leafed willow; we finally found him concealed in some very thick brush and shot him through the skull with two balls. . . .

They might well have shaken their heads in amazement:

we proceeded dress him as soon as possible, . . . we now found that Bratton had shot him through the center of the lungs, notwithstanding which he had pursued him near half a mile and had returned more than double that distance and with his tallons had prepared himself a bed in the earth of about 2 feet deep and five long and was perfectly alive when we found him which could not have been less than 2 hours after he received the wound

Captain Lewis was beginning to get a better grip on the grizzly.

these bear being so hard to die reather intimedates us all; I must confess that I do not like the gentlemen and had reather fight two Indians than one bear.

His choice of word in reference to Ursus horribilis, spontaneously drawn from his lexicon of manners and slightly tinged with sarcasm, was nontheless fitting. “Gentlemen” denoted landowners, and those beasts indisputably were the natural lords of this land. We may forgive his flash of bravado, also. He had not yet fought any Indians, and was to do so only once in his life—on July 27, 1806. But he would survive his own solitary showdown with a grizzly just five weeks later.

14 May 1805: Narrow Escape

One of their most harrowing experiences with a grizzly occurred on 14 May 1805, on the bank of the Missouri River between the Milk and Musselshell rivers. Clark wrote:

Six good hunters of the party fired at a Brown or Yellow Bear Several times before they killed him, & indeed he had like to have defeated the whole party, he pursued them Seperately as they fired on him, and was near Catching Several of them one he pursued into the river, this bear was large & fat would way about 500 wt

Lewis described the climax of the incident:

he pursued two of them seperately so close that they were obliged to throw aside their guns and poucnes and throw themselves into the river altho’ the bank was nearly twenty feet perpendicular; so enraged was this animal that he plunged into the river only a few feet behind the second man he had compelled to take refuge in the water, when one of those who still remained on shore shot him through the head and finally killed him.

When they butchered the animal, they found that a total of eight rifle balls had entered its body in different directions.

14 June 1805: ‘Not a Little Gratifyed’

Meriwether Lewis had his own close call with a grizzly on 14 June 1805. He had found the Great Falls of the Missouri on the previous day, and now set out alone to explore the river above—where he was to find four more falls and rapids. In the vicinity of today’s Riverfront Park in the city of Great Falls, Montana, and since it was late in the day he decided to kill some meat and make camp—whereupon he had what he was later to characterize modestly as “a curious adventure.”

Under this impression I scelected a fat buffaloe and shot him very well, through the lungs. While I was gazeing attentively on the poor anamal discharging blood in streams from his mouth and nostrils, expecting him to fall every instant, and having entirely forgotton to reload my rifle, a large white, or reather brown bear, had perceived and crept on me within 20 steps before I discovered him.

In the first moment I drew up my gun to shoot, but at the same instant recolected that she was not loaded and that he was too near for me to hope to perform this opperation before he reached me, as he was then briskly advancing on me. It was an open level plain, not a bush within miles nor a tree within less than three hundred yards of me. The river bank was sloping and not more than three feet above the level of the water. In short there was no place by means of which I could conceal myself from this monster untill I could charge my rifle.

In this situation I thought of retreating in a brisk walk as fast as he was advancing untill I could reach a tree about 300 yards below me, but I had no sooner terned myself about but he pitched at me, open mouthed and full speed. I ran about 80 yards and found he gained on me fast. . . . The idea struk me to get into the water to such debth that I could stand and he would be obliged to swim, and that I could in that situation defend myself with my espontoon. Accordingly I ran haistily into the water about waist deep, and faced about and presented the point of my espontoon.

At this instant he arrived at the edge of the water within about 20 feet of me. The moment I put myself in this attitude of defence he sudonly wheeled about as if frightened, ? retreated with quite as great precipitation as he had just before pursued me. & the cause of his allarm still remains with me misterious and unaccountable.

So it was, and I feelt myself not a little gratifyed that he had declined the combat.

28 June 1805: A Frolick?

On 28 June 1805, at their camp at the upstream end of the portage around the falls of the Missouri, Lewis complained:

The White bear have become so troublesome to us that I do not think it prudent to send one man alone on an errand of any kind, particularly where he has to pass through the brush. we have seen two of them on the large Island opposite to us today but are so much engaged that we could not spare the time to hunt them, but will make a frolick of it when the party return and drive them from these islands. they come close arround our camp every night but have never yet ventured to attack us and our dog gives us timely notice of their visits, he keeps constantly padroling all night. I have made the men sleep with their arms by them as usual for fear of accedents.

No wonder! The bears were then at the height of their spring feast, and the Corps of Discovery was sleeping on their banquet table.

15 May 1806: Twenty Distinct Colours

The hunters encountered so many grizzlies while the Corps was waiting out the spring thaw at Camp Chopunnish on the Clearwater River, that Lewis had good reason to expand upon his understanding of the grizzly bear. On 14 May 1806, he wrote:

These bears gave me a stronger evidence of the various coloured bear of this country being one species only, than any I have heretofore had. . . . The white and redish brown or bey coloured bear I saw together on the Missouri; the bey and grizly have been seen and killed together here for these were the colours of those which Collins killed yesterday.

In short, it is not common to find two bear here of this species presicely of the same colour, and if we were to attempt to distinguish them by their colours and to denominate each colour a distinct species we should soon find at least twenty.

They have attacked and faught our hunters already, but not so fiercely as those of the Missouri.

They bagged seven grizzlies during their month-long wait here on the west slope of the Bitterroot Mountains.

15 July 1806: McNeal’s Chapter of Accidents

Upon arriving back at the upper portage camp at White Bear Islands, on 15 July 1806, Lewis dispatched Private Hugh McNeal to the downriver end of the portage route to find out whether the cache was still intact and if the white pirogue had wintered alright. McNeal never made it to his destination on that trip, but added another dramatic episode to the saga of the grizzlies:

A little before dark McNeal returned with his musquet broken off at the breach, and informed me that on his arrival at willow run he had approached a white bear within ten feet without discover[ing] him the bear being in the thick brush. The horse took the allarm and turning short threw him immediately under the bear; this animal raised himself on his hinder feet for battle, and gave him time to recover from his fall, which he did in an instant and with his clubbed musquet he struck the bear over the head and cut him with the [trigger-]guard of the gun and broke off the breach, the bear stunned with the stroke fell to the ground and began to scratch his head with his feet; this gave McNeal time to climb a willow tree which was near at hand and thus fortunately made his escape. the bear waited at the foot of the tree until late in the evening before he left him, when McNeal ventured down and caught his horse, which had by this time strayed off to the distance of 2 ms. and returned to camp. these bear are a most tremenduous animal; it seems that the hand of providence has been most wonderfully in favor with rispect to them, or some of us would long since have fallen a sacrifice to their farosity. there seems to be a sertain fatality attached to the neighbourhood of these falls, for there is always a chapter of accedents prepared for us during our residence at them.

2 Aug 1806: Large Vicious Species

On 2 August 1806, on the Yellowstone River near Glendive, Clark himself shot a grizzly:

about 8 A.M. this morning a Bear of the large vicious Species being on a Sand bar raised himself up on his hind feet and looked at us as we passed down near the middle of the river. he plunged into the water and Swam towards us, either from a disposition to attack’t or from the Cent of the meat which was in the Canoes. we Shot him with three balls and he returned to Shore badly wounded. in the evening I saw a very large Bear take the water above us. I ordered the boat to land on the opposite Side with a view to attack’t him when he Came within Shot of the Shore. when the bear was a fiew paces of the Shore I Shot it in the head. . . . the men hauled her on Shore and proved to be an old Shee which was so old that her tusks had worn Smooth, and Much the largest female bear I ever saw.

6 Aug 1806: Mistaken Identity

On 6 August 1806, near present Williston, North Dakota, the men saw their last grizzly. Clark reported it:

This morning a very large Bear of white Specis, discovered us floating in the water and takeing us, as I prosume to be Buffalow imediately plunged into the river and prosued us. I directed the men to be Still. this animal Came within about 40 yards of us, and tacked about. we all fired into him without killing him, and the wind So high that we could not pursue hi[m], by which means he made his escape to the Shore badly wounded.

Clark had seen dead buffalo floating downstream, drowned as the herd forded the river above.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.