Missouri River geology consists of exposed rock formations that are geologically diverse, distinctly colored, and rich in mineral content. In some places, steaming and smoking hot earth beckoned Lewis to investigate.

Related Pages

La Vérendrye’s 1728 name for Spirit Mound contains several puzzling statements. Pako’s reference to that “very fine gold-coloured sand,” suggests the “little mountain” was located in a fabulous land, an Eldorado, of precious natural riches.

As a professional geologist and a Lewis and Clark enthusiast I’m impressed by what the captains had to say about the geology of the Upper Missouri River Breaks, as suggested by the following journal excerpts and commentary.

Lewis and Clark reported seeing layers of coal along the Missouri River’s northern reach. Jefferson had only to look to Great Britain, already fifty years into the Industrial Revolution, to see what was coming.

The Fort Union Formation

by Robert N. Bergantino

Today it is a high and dry plain, but sixty million years ago it was a shallow saucer in the earth’s crust, filled with warm, steamy tropical jungles. That rich, dense vegetation would, over some millions of years, become a huge, complex deposit of lignite.

The huge meander called the Big Bend, or Grand Detour, had been a well-known Missouri River landmark for many years when the Corps of Discovery arrived at its lower bend on 19 September 1805.

The Missouri River exposed rock formations that were geologically diverse, distinctly colored, rich in mineral content, and in some places, dramatically distinguished by steaming and smoking hot earth that beckoned to be investigated.

“at this place there is a large rock of 400 feet high wich stands immediately in the gap which the missouri makes on it’s passage from the mountains.”

Pumice Stone

by Robert N. Bergantino

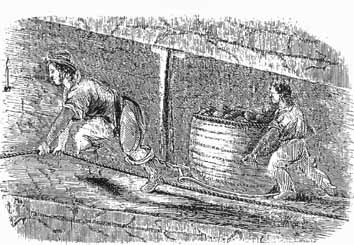

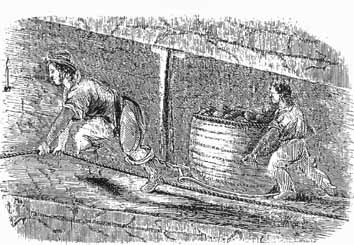

“The Pumies Stone which is found as low as the Illinois Country is formed by the banks or Stratums of Coal taking fire and burning the earth imedeately above it into either pumies Stone or Lavia. This Coal Country is principly above the Mandans.”

The lignite in the Fort Union Formation ignites easily. Sometimes the materials adjacent to the burning coal beds become so hot that they actually froth and, when cooled, resemble the bubbly and cratered volcanic rock called pumice.

Lewis and Clark sometimes called this coal “carbonated wood” because sometimes they could see the outlines of woody stems and other plant remains. Coal geologists call it lignite, but Lewis and Clark were essentially correct in their description.

Searching for Lead

by John W. Jengo

In the afternoon of 4 June 1804, William Clark decided to investigate the purported occurrence of lead in the vicinity of a rather unique prominence he named “Mine Hill,” but which is known today as Sugar Loaf Rock. The search was unsuccessful, but Lewis’s previous inquiries while in St. Louis resulted in 11 specimens sent to Thomas Jefferson.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.