And he, who, now to sense, now nonsense leaning,

Means not, but blunders round about a meaning.

Frank Woody’s Research

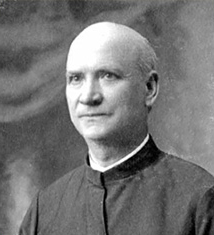

Two Gentlemen of Montana

Duncan McDonald and Frank Woody

Image 90-0018 (left) and Image 76-1193 (right)

Archives & Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana

Duncan McDonald (1849-1937), the son of a Scottish father and a Nez Perce-Iroquois mother, was born at the HBC’s Fort Connah on the Flathead Reservation, which his father had founded in 1847, and grew up to be the Clerk in charge of the trading post during the last four years of its existence (1867-71). Rigorously mentored by his father, who himself spoke Gaelic, English, French, and six Indian languages and who hired tutors to refine his son’s education, Duncan spent his life in a vibrant cross-cultural milieu. He was unquestionably the most admired, respected, and influential mixed-blood citizen in the region.[1]Lawrence Barkwell, Coordinator of Metis Heritage and History Research, Louis Riel Institute, at http://www.scribd.com/doc/49098440/Duncan-McDonald (accessed 8 June 2011). Terry C. Johnson, Lay the … Continue reading

Frank Woody (1833-1916), a native of North Carolina, arrived in the Bitterroot Valley from Salt Lake City by oxcart in 1856, worked for a while making adobe bricks at Fort Owen, then, in 1860, helped Frank Worden and Christopher Higgins establish their general store in Grass Valley on the Clark Fork River. It was the first structure in what was soon to become the city of Missoula. He taught himself jurisprudence, and at age 29 was elected to serve as the prosecuting attorney in the first murder trial at Hell Gate. Later he was admitted to the bar, soon becoming a probate judge in Missoula, and eventually a district judge for the State of Montana.

Only a few years short of a century after Lewis and Clark traced Travelers’ Rest Creek for the second and last time, Olin D. Wheeler, a press agent for the recently completed (1883) Northern Pacific Railroad, became interested in the origin of the name “Lolo.” (Apparently he knew better than to spell it “Lou-Lou.”) That was in 1899, on his first trip west, when he visited and photographed the Lolo Hot Springs. He then began making inquiries among the “old settlers,” including the Jesuit missionaries, who had been in Montana “since early days.” By virtue of their longevity, all were qualified as fountains of historical information. From them Wheeler learned that there were “several plausible stories current regarding this name.” He was soon introduced to Judge Frank Woody of Missoula, who consented to lead an investigation of the matter in Wheeler’s behalf. When Wheeler returned to the Rockies in 1903, he was confident that Woody had “arrived . . . at the truth in the matter,” so he published Woody’s own words in his two-volume travelogue, The Trail of Lewis and Clark.[2]Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904: a story of the great exploration across the continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and … Continue reading

Woody himself had been curious about that name, and after some reflection, as well as consultations with reliable authorities of his acquaintance, he wrote:

That the name, Lolo, is the nearest that the Indians could get to ‘Lawrence,’ I have no longer any doubt. Father D’Aste and Father Palladino, who are among the oldest of the Jesuit Fathers now living, are both of this opinion.[3]Neither of the priests Judge Woody consulted could be called “old-timers.” Jerome D’Aste S.J. (1828-1910) was in charge of the second St. Mary’s Mission from 1876 until its … Continue reading They say that they have known more than one instance in which men by the name of Lawrence have been called Lolo by the red men. Duncan McDonald, who is one of the best informed men in the Northwest regarding the early history of the Indians, coincides with this opinion. Since I have been engaged in this research, I have received several letters from different parts of the state in regard to the subject, and nearly all of them are in support of this theory.

The Indian whose name was given by the whites to this stream was well known to many of the early residents and, I am told by Duncan McDonald, was a famous hunter and trapper. McDonald is so well informed regarding these matters, that I accept his statement as a fact. The name evidently came from the name of this Indian, whose baptismal name had been corrupted by the red men from Lawrence to Lolo.[4]Wheeler, 2:78.

From Lawrence to Lolo

Indians, Fr. Palladino explained, “are wont to call people, even Fathers and Brothers, by this or that exterior peculiarity, which they are quick to notice in persons.” For example, he pointed out, Father Giorda was “Round Head,” Father Grassi was “Left-Handed,” and Father Cataldo was “Broken Leg.”

Father Palladino himself was an exception to that convention. Since the sound of the letter r, either fricative or uvular, and the nasal French n in his Christian name, Lawrence (Laurent in French), were both unpronounceable by the Salish, he was known by the customary abbreviation, “Loló.”[5]Lawrence B. Palladino, S.J., Indian and White in the Northwest: A History of Catholicity in Montana, 1831 to 1891 (Lancaster, PA: Wickersham Publishing Company, 1922), 67.

Curiously, Judge Woody did not say—or perhaps did not know—that one of his consultants, Lawrence Benedict Palladino, S.J., himself was known by the Indians of that region as “Lolo.” Nor did anyone recall the killing of a man named Lolo by a grizzly bear in late 1850. Perhaps they had good reason to believe that it was a different, non-Christian Lolo whose name was applied to the creek, the hot springs, and the pass. Certainly there were other Lolos in the vicinity from time to time, as Thompson, Mullan and Owen noted in their journals. Even up at the Jocko Indian Agency in 1894, Father D’Aste reported in his diary for June 21 that he “got a sick call to Lolo who was stabbed by a drunken Indian.”[6]Robert Bigart, Zealous in all Virtues: Documents of Worship and Culture Change, St. Ignatius Mission, Montana, 1890-1894 (Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College, 2007), 274.> Moreover, the Judge neglected to mention that on 30 November 1899, he sentenced an Indian named Lolo to eighteen months in the state penitentiary for murdering a fellow Indian named Ambrose in a whiskey-fueled fight.[7]Dateline Missoula, 27 November 1899; Special to the Butte Weekly Miner (Butte, MT). Infotrac, 19th Century U.S. Newspapers (retrieved 10 August 2011). In a background letter to the Missoula County … Continue reading Nobody said that the Christian name of any of those Lolos was Lawrence.

The name Lawrence is absent from all of the standard rosters of fur trappers and traders that exist today, although, as we have just seen, it did become a common name among the Flatheads, or Bitterroot Valley Salish. The first time, and for many years the only time, that it appeared in the historical literature of North America was as the name of the river that drains the Great Lakes into the Atlantic Ocean, which was named by the faithful Jacques Cartier when he entered its estuary on 10 August, the feast day of the 3rd century Christian martyr, Saint Lawrence—or Laurent—of Rome.

Duncan McDonald’s Stories

One November day, 12 years after Olin D. Wheeler’s book was published, the loquacious Duncan McDonald sat down in the office of The Daily Missoulian and explained the reason for his visit.[8]“How Lolo Got His Name,” The Daily Missoulian, 26 November 1916, Editorial Section, p. 4, cols 2-3. He had recently seen Judge Woody’s accounts of some Montana place-names, and was surprised to see that “the judge fell into the usual error regarding the origin of the name Lolo.” Various authorities, he said, all seemed to agree that it “must have been some old Indian name as the original spelling 40 years ago was Lou Lou.” That was the mistake. It was officially changed to Lolo, he pointed out, when the first post office was opened there in 1888.

With credit to his late Salish mother-in-law, who had often retold the story, McDonald sought to set the record straight. “The original Lolo,” he began, “was a half-breed Frenchman by the name of Laurent, who lived with the Flathead Indians . . . in the early part of the last century.” He knew nothing about Lolo’s birthplace or parentage, but figured he was in one of the HBC’s fur brigades that explored the mountains in the vicinity of Hellgate Ronde early in the 19th century. He reiterated the fact that the Salish had no r in their language, so in English words such as Lawrence they substituted an l, which is produced much like the gentle fricative, tip-of-the-tongue rhotic. “You know,” he said, “that Laurent, in French, is the equivalent in the English language to the name Lawrence, and is pronounced La-ra, so the Indians called it La La.” With a little imagination, the reporter might have compared the second syllable of lo-rawn’ with the sound of “haunt” sans the final t, but it obviously didn’t occur to him. McDonald’s good intention was foiled by the reporter’s arbitrary alternative.

Notes

| ↑1 | Lawrence Barkwell, Coordinator of Metis Heritage and History Research, Louis Riel Institute, at http://www.scribd.com/doc/49098440/Duncan-McDonald (accessed 8 June 2011). Terry C. Johnson, Lay the Mountains Low (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 699. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904: a story of the great exploration across the continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later, 2 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 2:78. |

| ↑3 | Neither of the priests Judge Woody consulted could be called “old-timers.” Jerome D’Aste S.J. (1828-1910) was in charge of the second St. Mary’s Mission from 1876 until its closure in 1891; Lawrence (French Laurent) Benedict Palladino (1837-1927) was one of the founders, in 1867, of St. Ignatius Mission, 70 miles north of St. Mary’s in the Bitterroot Valley. “Written Historical and Descriptive Data for St. Mary’s Mission.” Historic American Buildings Survey, Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, National Park Service, 2006. |

| ↑4 | Wheeler, 2:78. |

| ↑5 | Lawrence B. Palladino, S.J., Indian and White in the Northwest: A History of Catholicity in Montana, 1831 to 1891 (Lancaster, PA: Wickersham Publishing Company, 1922), 67. |

| ↑6 | Robert Bigart, Zealous in all Virtues: Documents of Worship and Culture Change, St. Ignatius Mission, Montana, 1890-1894 (Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College, 2007), 274. |

| ↑7 | Dateline Missoula, 27 November 1899; Special to the Butte Weekly Miner (Butte, MT). Infotrac, 19th Century U.S. Newspapers (retrieved 10 August 2011). In a background letter to the Missoula County Attorney, Duncan McDonald revealed that this Lolo was a cousin of his, and that both Lolo and his victim were Mohawk/Iroquois half-breeds. Anaconda [MT] Standard, 3 December 1899, p. 14, col. 2. |

| ↑8 | “How Lolo Got His Name,” The Daily Missoulian, 26 November 1916, Editorial Section, p. 4, cols 2-3. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.