Even though it is highly unlikely that any of the expedition’s journalists ever heard the name, Lolo is among the most familiar and useful of all the place names in the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition. How did the Lolo get its name?

Bitterroot Valley businessman John Owen counted no Lolos among the customers he dealt with at Fort Owen, but he occasionally hired one as a trail-hand.

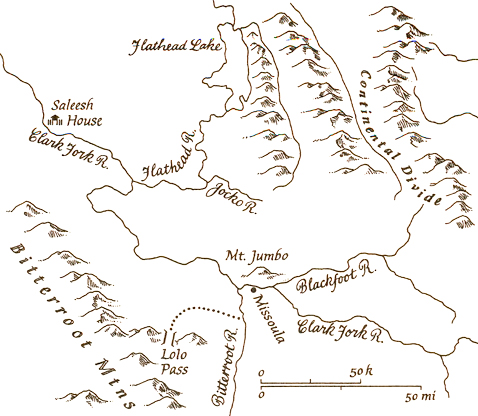

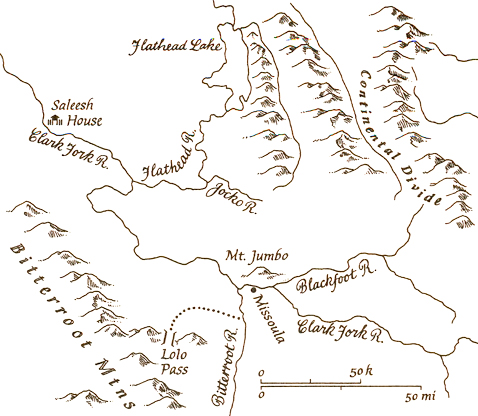

Lewis and Clark and their men camped on 9–10 September 1805 and again on 30 June though 2 July 1806 beside a stream they called “Travelers Rest Creek.” Meriwether Lewis may have seen or sensed a comparison between it and the Travelers Rest in South Carolina.

Lewis and Clark’s name “Travelers Rest” was too site-specific to simultaneously function equitably with the creek, the peak, the hot springs, the pass, and all the rest. By the time settlers began moving into the region, the old name was basically meaningless.

He spent most of his 70 years at Fort Kamloops in British Columbia and is not known to have traveled as far south as today’s Lolo, Montana.

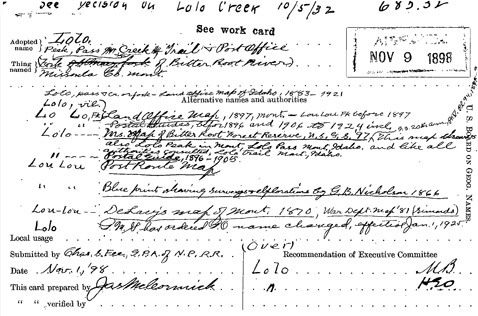

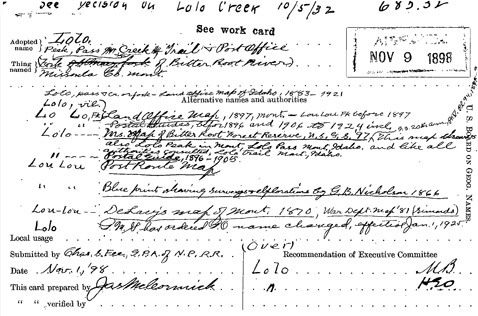

Whereas Lt. Mullan consistently referred to the creek as Lolo’s Fork, Isaac Stevens, in the published Reports and Surveys, and in all of the related maps, embellished Lo Lo with a supplementary u, making it “Lou Lou,” which led to the logical conclusion that the name was pronounced “Loo Loo.”

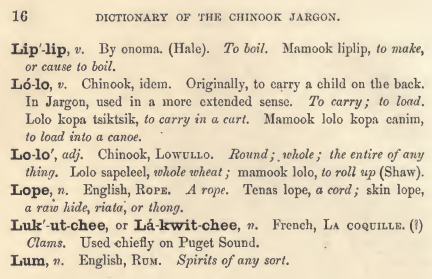

The verb, lolo, in the Chinook Trade Jargon, meant “to carry, load, bear, bring, fetch, transfer, lug, or pack.” Thus a “lolo” was a “carrier.”

One amateur historian averred that it was “a corruption of the French name Le Louis, given to the stream and pass by early French trappers” in honor of Meriwether Lewis. Another claimed that the mystery [wo]man was named after “Lolo [i.e., Lola] Montez, a noted Spanish beauty.”

The closing of the first St. Mary’s Mission on 5 November 1850 was punctuated by the sudden death of “Lolo, the only Indian who still remained well disposed and really attached to religion.”

Among the most faithful of the missionaries’ converts to Catholicism was a half-breed trapper named Lolo who was killed by a grizzly bear in November 1850.

The U.S. Board on Geographic names declared that “Lou-Lou” and “Loo-Loo,” as well as the sometimes hyphenated “Lo-Lo,” were not to be used on maps in the future, and that the official place-name from that time forward was to be Lolo.

Around 1900, Olin D. Wheeler, initiated an inquiry into the source and meaning of the name Lolo. He secured the aid of Judge Frank Woody of Missoula, who in turn discussed the matter with some other “old-timers.”

Lt. John Mullan surveyed the Northern Nez Perce road across the Bitterroot Range in 1853-54 to assess its suitability as a railroad route. He never met anyone named Lolo, but was told by an Iroquois guide and interpreter that the creek was called the “Lo Lo Fork,” or “Lo Lo’s Fork.”

The first written record of a man named Lolo appeared in the field notes of David Thompson while at today’s Kettle Falls on the Columbia River. Fifteen years later, trader John Ashley mentions a “Mr. Lolo.”

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.