An ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, important documents were written on specially prepared sheep or goat skins called parchments, or on a flat, flexible material manufactured from an aquatic flowering sedge called Cyperus papyrus. Both parchment and papyrus were sturdy enough for the ink to be scraped off and the writing-sheets used for new documents, although often showing faint evidence of the erasures. The result was a multilayered record of some aspect of the past. A recycled parchment or papyrus (pap-PEYE-rus) was called a palimpsest (PAL-imp-sest), a Latin word derived from two Greek sources, palin, “again,” and psen, “to scrape.” Because the writing fluid or “ink” varied in viscosity, and the texture beneath the writing surface could be more absorbent in one place than another, the erasures could not always be complete, for fear of scraping holes through the material, and more or less faint shadows of words, parts of words, and relatively long passages of text could remain dimly legible. Therefore, as historian William J. Peterson pointed out, “it became a fascinating task for scholars not only to translate the later records but also to reconstruct the original writings by deciphering the dim fragments of characters partly erased and partly covered by subsequent texts.”

By extension, the word palimpsest can refer to any document that contains more or less obscure clues to its own history. An out-of-date map, for instance, the older the better, may be likened to an ancient palimpsest. A printed chart does not normally contain erasures, but it is made up of a map-maker’s shorthand—ostensibly meaningless verbal and non-verbal symbols that can be pried open by dedicated antiquarians, and flood the page with human impressions, imagery, and understanding. It becomes an evanescent namescape as varied and interesting as the solid landscape. The travel routes it contains may reflect long-forgotten geopolitical, cultural, and technological circumstances that reward the patient student. Its place-names make up a toponymy of human ambitions, experiences, and feelings, even the sounds of forgotten languages, all rubbed thin by the passage of time, leaving each bygone story stuffed into one or two cryptic words. (Who was that man called Lolo, and how did his name come to displace Lewis’s own, thoughtful placename, “Travelers’ Rest“?) “To decipher these records of the past,” Peterson reminded us, “and tell the stories which they contain is a task of those who write history.”[1]These words of William J. Petersen (1901-1989) are quoted from the masthead of The Palimpsest, a monthly journal of Iowa history, which he founded in 1947 and edited until 1973, contributing to it … Continue reading

Clark’s View of Siouxland

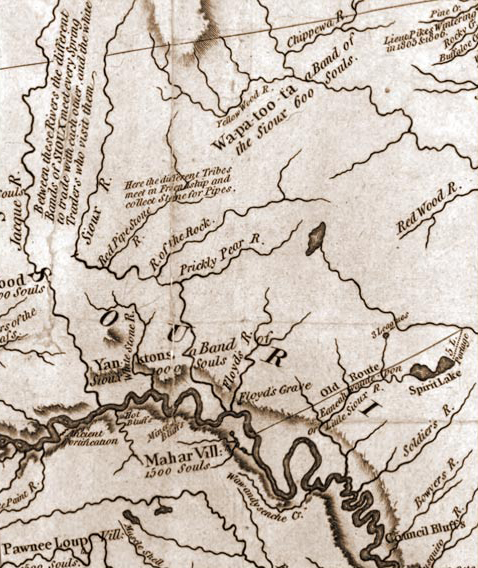

The historic Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America, which was published in 1814 as part of Nicholas Biddle‘s History of the Expedition under the Commands of Captains Lewis and Clark, can fruitfully serve as a major palimpsest of American history as of the year in which it was created, 1810. As an exercise, and a model for the reader’s future consideration, we shall examine a detail from Clark’s 1810/1814 map anchored on Sioux City, Iowa.

The region encompassed by this segment of Clark’s 1814 map was described in some detail in the long narratives in Clark’s “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” and Lewis’s “Affluents of the Missouri River.” For a few decades Clark’s map served the same purpose as our modern road maps—to facilitate travel in territory previously unknown to the traveler. From the early 1840s on, however, as river-borne westbound emigrant traffic increased in volume and pace, especially with the advent of the steamboat, it steadily grew less useful. Today, this vignette from Clark’s map is a snapshot of a moment of history that allows us to contemplate the changes that occurred as the broad frontal line of white Euro-American civilization surged westward during the middle decades of the 19th century. Fundamentally, it is a paradigm of the stages that followed in the western frontier’s surge toward the Pacific Coast.

Sioux Exonym

Sioux is an exonym,[2]An exonym is a name by which one Indian tribe or nation refers to another, and by which the group so named doesn’t use for itself. “Nez Perce,” for example, is an exonym meaning … Continue reading or foreign, in this case French Canadian name via an Ottawa Indian exonym, Nadoueessioux (“Enemies”), for a large and varied nation of native American tribes that migrated westward from the sources of the Mississippi River in the late 1600s. On 31 August 1804, Clark, frustrated in his attempt to draw a clear picture of the Sioux nation, summarized what he did know. “This Nation is Divided into 20 Tribes possessing Seperate interests . . . . Collectively they are noumerous Say from 2 to 3000 men, there interests are so unconnected that Some bands are at war with Nations which other bands are on the most friendly terms.” However, he learned only 12 “names of the Different Tribes . . . of the Sceoux or Dar co tar Nation. . . . The names of the other bands neither of the Souex’s interpters could inform me.”[3]Moulton, Journals, 3:419-20; 3:354-57. For more, see on this site Siouan Peoples.

Mahar

The Mahar or Omaha people, whose riverside village was a local landmark for Lewis and Clark, were once “the terror of their neighbors,” including the Sioux, but they were decimated by smallpox in 1802, as was the smaller but equally warlike Iowas tribe. The Pawnee Loup (Wolves) were “friendly, well disposed” hunters and farmers.

Old Route

Clark’s “Old Route” probably was the west end of the well-traveled overland “Road of the Voyageurs” that connected the Mississippi River at Prairie du Chien with the villages of the Omahas and Iowas on the Missouri near the headland that was to become Floyd’s Bluff. Neither Lewis nor Clark claimed to have seen the road, but may have noticed it on their copy of the map by Guillaume Delisle (1675-1726), or been told about it by Pierre Dorion.

Spirit Lake

A band of 14 desperate, starving Santee Sioux murdered nearly 40 Iowa settlers in the vicinity of Spirit Lake, about 90 air miles northeast of Sioux City, and kidnapped four young women for ransom. That was in March of 1857. Five years later, as a consequence of the federal government’s failure to honor its own treaty obligations, exacerbated by dishonest agents who withheld food and funding, the conflict exploded into even bloodier, if mercifully brief, warfare. Upon its close, thirteen Sioux men were hanged. But that was only the beginning. For nearly 30 years the remnants of the Sioux Nation continued to hope for a return to the glory they had known during the opening decades of the 19th century, a glory that William Clark recorded in this piece of the map he created in 1810, and released into an already changed world in 1814.

Their valiant hopes were wrenched from their hearts by the brief but forever horrible Massacre beside Wounded Knee Creek, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. It lasted but a few hours on the morning of 29 December 1890, just a few miles up the Missouri River from the now-flourishing city of 38,700 souls named for the nation of the Siouan-speakers. And as the life’s blood of each of the 300 Sioux casualties flowed out on the bank of the Wounded Knee, it carried the first-hand memories of the older men, and the revered elders’ tales from the younger, about the traditional springtime gatherings between the contrary-flowing waters of the Sioux and the Jacque. About the journeys to the red pipe stone quarry to mine the soft, rich-red raw material to be lovingly shaped into pipes that celebrated peace and friendship. Gone. All Gone.

Sioux City

Iowa was admitted to the U.S. as the 29th state in 1846. Within two more years an otherwise anonymous man named William Thompson built a cabin at the foot of the bluff below Floyd’s grave. The following year a French-Canadian trader for the American Fur Company hopefully settled at the mouth of the Big Sioux River. In 1854 a surveyor for the U.S. government laid out a town between the Big Sioux and Floyd’s River, a logical place for a settlement, inasmuch as it had long been a favored fording place, campsite and gathering point of the Yankton Sioux and other Native tribes. Within another 12 months or so, the new town’s small proud populace thrilled to the arrival of the first steamboat, 8 or 9 days from St. Louis, compared with Lewis and Clark’s 98 days from St. Charles whereby Sioux City was reassuringly linked with the rest of the world.

In the autumn of 1857, while recovery from the previous spring’s flood was still scarcely begun, the distant rumbling of the international economy, and the ominous cumuli of the domestic economy, a stormy financial crisis began to drench the pioneer state, built as it was upon guts, promises, and borrowed money. Evidently, few memorable lessons were learned from the Panic of 1857 besides its unforgettable name.

Pipestone Quarry on the Coteau des Prairies (1836-37)

George Catlin (1796-1872)

Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1985.66.337.

Red Pipestone River

The peripatetic western artist George Catlin (1796-1872) claimed to have been the first white man to see the famous Indian pipestone quarry in Minnesota, in 1836. The pipestone used by Indians for untold centuries came to be called catlinite because the American artist George Catlin. A prior visit, however, had been made by the frontiersman Philander Prescott (1801-1862), who described the quarry over near Flandreau, South Dakota, in 1832, but that fact was not widely known until 1966, when his journal was first published. Forty miles up the “Red Pipe Stone R.” is the quarry.[4]Donald Dean Parker, ed., The Recollections of Philander Prescott, Frontiersman of the Old Northwest, 1819-1862 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 130-39.

Bowyers River

Clark spelled it “Boyer” in his journal, but “Bowyer” on his 1814 map. It’s 118 miles long, said now to have been named for a settler who hunted and trapped in the watershed sometime before the Corps of Discovery passed by in 1804. John James Audubon and Maximilian mentioned it as they ascended the Missouri. Charles Floyd, ill but not yet out of commission, recorded on 29 July 1804, that they had “passed the mouth of Boyers River on the N. Side it about 30 yards wide the Land is Low Bottom Land out from the River is High Hills.”

The name must have struck a familiar note in Lewis’s memory when, on 16 June 1805, he tasted the water of the “Sulphur Springs” across the Missouri from the Lower Portage Camp, it brought to mind the “Bowyer’s Sulpher spring” he knew of back home in Virginia.

It is almost certain that Alex Willard never forgot that day, 29 July 1804, when he earned a reputation as somewhat of a screw-up. First, at about midday he was sent back 3¼–4 miles overland to the previous night’s campsite to fetch his tomahawk, which he had left laying somewhere. He found it, and jubilantly turned toward the boats an hour’s hike upriver. On his return upriver he crossed the 75-yard-wide creek on a log, and nearly fell in. Either the log was narrow and bouncy, and he lost his balance, or it was thick and full of branches that he had to thread his way through, and he tripped on one; or it was a dead tree and the bark fell off under his feet, or the bark was entirely missing and the bole was slippery. Evidently the real cause wasn’t deemed important enough to write down. In any event, he “let his gun fall in,” according to Clark.[5]Moulton, 2(Clark):427; 9(Ordway):31; 11(Whitehouse):17. For some reason, he couldn’t retrieve it himself, so he had to race back to the barge for help. Reubin Field was ordered to make the dive.

As Clark explained it, Private Willard “in attempting to Cross this Creek on a log let his gun fall in. R. Fields Dived & brought it up.”[6]Moulton, 2:427.

In 1894 a grand plan conceived by the federal Missouri River Commission was put in place to reduce riverside farmers’ losses from spring floods, impound water for late-season irrigation, and maintain a consistent level on the lower reaches of the Missouri to facilitate river commerce. The first dam in the Commission’s plan, completed in 1962, was built the Gavins Point Dam at Yankton, South Dakota, 80 river-miles upstream from Sioux City.

Highland of the Prairies

Early French explorers such as Father Louis Hennepin (1626-c. 1701) called it Coteau des Prairies, while Captain Clark rendered it perhaps with help from the party[s] pro tem interpreter Pierre Dorion as “Mountain of the Prairie,” although “Highland of the Prairies” would have been a more literal translation. By 1840 it was commonly known as “The Beautiful Meadow,” which is more descriptive inasmuch as its sides are not steep but gently sloping. Geologically, it is a huge terminal moraine left over from the last Ice Age, averaging 200 miles from north to south and 100 miles from east to west. Its highest elevation is 1900 feet above Mean Sea Level. The Jacques or James River flows from the west flank of the plateau; the Red River of the North and the south-flowing Minnesota River (St. Peter River in Clark’s day) rise on its eastern slope. The Coteau des Prairies is surrounded by the fertile plains and loess hills of eastern South Dakota, southwestern Minnesota, and northwestern Iowa.

Notes

| ↑1 | These words of William J. Petersen (1901-1989) are quoted from the masthead of The Palimpsest, a monthly journal of Iowa history, which he founded in 1947 and edited until 1973, contributing to it nearly 400 articles of his own. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | An exonym is a name by which one Indian tribe or nation refers to another, and by which the group so named doesn’t use for itself. “Nez Perce,” for example, is an exonym meaning “pierced noses.” But they have always called themselves Nimeepoo, which means “The People.” |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 3:419-20; 3:354-57. |

| ↑4 | Donald Dean Parker, ed., The Recollections of Philander Prescott, Frontiersman of the Old Northwest, 1819-1862 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 130-39. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, 2(Clark):427; 9(Ordway):31; 11(Whitehouse):17. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, 2:427. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.