Traveler’s Rest to Packer Meadows

To see labels, point to the map.

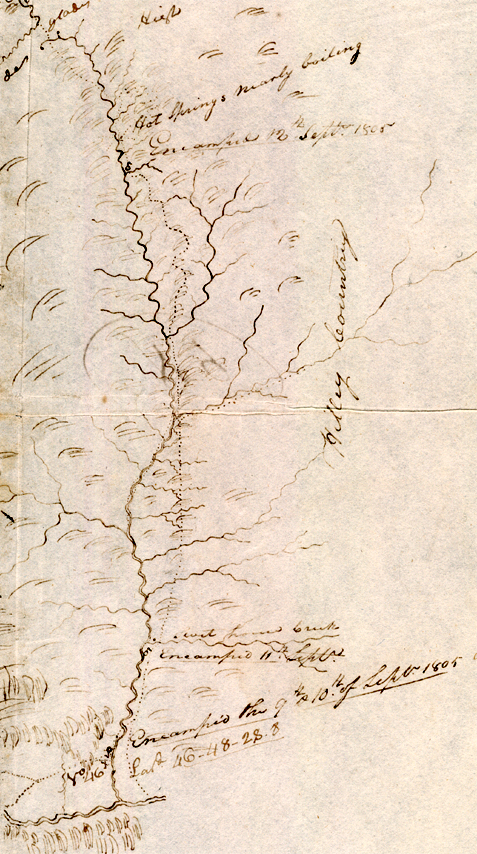

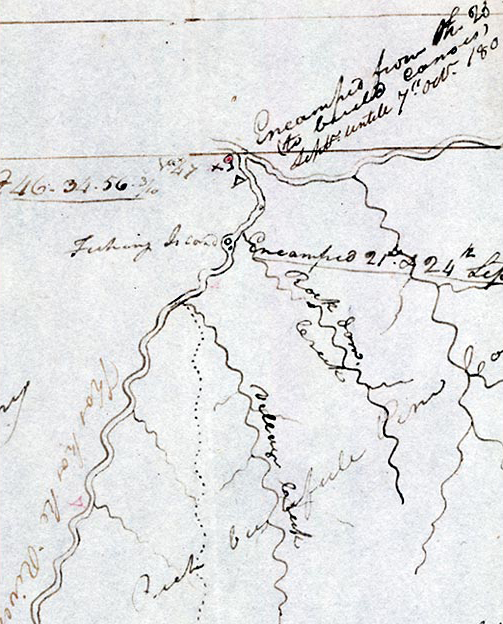

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. From Moulton, Atlas, Map 69, Detail.

This short stretch of Indian road was the interface between the Rocky Mountain barrier and the High Plains, anchored in important travel hubs. At the east end was a long-established gathering-place, resting-point, safe-house, and communication center for mountain peoples. Lewis and Clark called it ‘Travelers’ Rest.’ At the west end was a spa where more roads converged from the north. The explorers did not give it a name, nor did they record an Indian name. On the Bitterroot Divide, eight miles to the south, was a major seasonal food-mart featuring camas; just south of the divide, down at the headwaters of the Lochsa River, was a meat department offering fresh salmon and elk in season.

The latitude of Travelers’ Rest, calculated at Point of Observation No. 46, actually refers to a point about three miles north, which would be roughly under the .8 in the figure 28.8. The actual latitude at the center of the site where the Corps camped has been determined to be 46°44’58” North. The longitude, which the captains did not calculate, is 114°05’16” West.[1]Robert N. Bergantino, An Evaluation of Original Lewis and Clark Information to Determine the Location of Travelers Rest Camp, Lolo, Montana (1998).

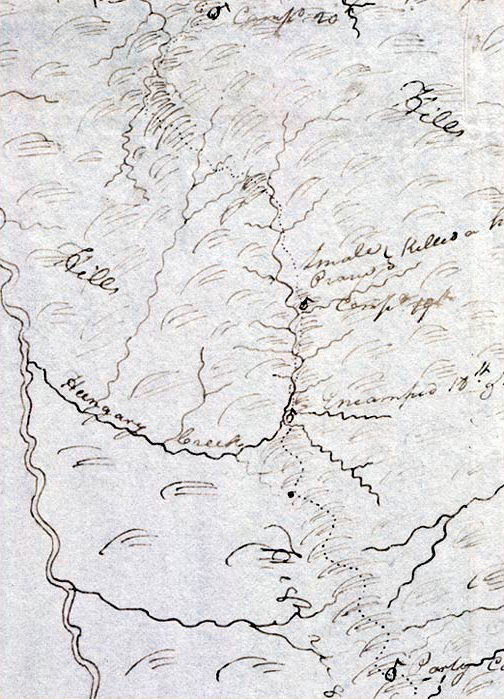

Mapping the Lolo Trail

Clark named only eight of the more than 200 streams he drew on his maps between Packer Meadows and Clearwater Canoe Camp. He simply noted the number of “dreans”—drainages—or watercourses to the right or left of their line of travel. A typical daily record from his courses and distances, for 17 September 1805, reads: “S. 50° W. 10 miles over high Knobs of the Mountn. emincely dificuelt, passed 3 dreans to our right to one which passes to our left on the top of a high Mountain, passing on a divide ridge.”[2]See Moulton, Journals, 5:237-40; 9:231-32; Atlas maps 69-71. Clark named Glade (today, Pack) Creek, Killed Colt Creek, Hungery Creek, Collins (Lolo) Creek, Village (Jim Ford) Creek, Rock Dam … Continue reading

The purpose in applying modern names to the streams on Clark’s map is to show that he did not randomly insert wiggly lines merely to hint at the topography around K’useyneiskit. By comparing his sketches with a modern USGS map we can make reasonably good guesses as to what drainages he actually saw. Hour by hour he was grasping with his mind the shape of the land in related patterns of hydrographic units.

A singular characteristic of these maps, compared with his charts of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, is the absence of any attempt to graphically represent the daily courses (compass bearings), or the relative distances traveled on each bearing. In fact, he estimated straight-line distances in only one or two courses per day for the entire traverse. At one point he estimated that the actual distance traveled on the “windings” was at least twice his straight-line figure. Clark estimated the total mileage, westbound, between the Bitterroot Divide (Packer Meadows) and Weippe Prairie at 128 miles. The eastbound mileage log totalled 118 miles between the same two points. The unintentional detour down to the Lochsa fishing site on 14–15 September 1805, would partly account for the difference.

Map Names

Names on maps are the rich placer lodes of oral history. They’re mostly dust, buried deeply beneath the weight of time and events. But now and then a small nugget of true adventure is found. The details of those names’ stories are often left, at best, to the authority of anyone old enough, and familiar enough with the place or the person, to win credibility on those accounts alone. At worst, their meanings are left to anyone with a vivid imagination and a gullible audience, which would include miners, trappers, packers, rangers, firefighters, sheepherders, hunters—or anyone who says he or she knows an old miner, trapper, ranger, and so on—who. . . .

But except for a few that have spawned good campfire tales, those names are just like bails without buckets—handy, but holding nothing. Nevertheless, placenames become as unassailable as scripture. They usually serve only, although quite sufficiently, to enable a person to tell someone else where he or she is, or has been, or would like to be. But every name on every map is a more or less secret, tightly encapsulated story.

Take Packer Meadows. One old-timer claimed that a trapper called Packer (was that his first, last, or nick?) who once (but when?) planned to homestead there. He built a cabin, it is rumored, but didn’t stay long. On the other hand, a photograph taken in 1969 proves that two brothers named Anderson did in fact build a log cabin on the edge of the meadows around 1914. They moved out (no one knows when or why), leaving their rough-hewn domicile to molder into the forest floor, and taking their full names and their tales with them into obscurity. Perhaps the name Packer Meadows merely signified that travelers used that “pretty little plain” to rest and feed their livestock before, or after, traversing those dreadful mountain ridges, saddles and peaks to the west.

The history of the early fur trade, which ended with the last Green River Rendezvous in 1840, is a rich romance that has become legendary. But it was a summer idyll compared with the next era of fur trapping, which drew upon high-country creatures such as mink, marten, bobcat, and bear, that could only be harvested in the dead of winter, when their fur was dense and long. It began in the 1850s and lasted until the early 1940s.

Unfortunately, the story of the latter-day breed of trappers is richer than the biographies of its participants. In 1905, trapper Charley Powell, perhaps then in his fifties, and almost a “senior citizen” by the measurements of that day, set up camp on the flat at the confluence of Clark’s Killed Colt Creek and the Brushy Fork, near the fish weirs Lewis and Clark had seen on 13 September 1805 a hundred years before. Sometime during that era another trapper built a cabin at the place near the Indians’ fish weir a few miles farther down the Lochsa, where the Corps turned north to climb out of the Lochsa canyon. The cabin has long since rotted away, but its builder’s last name, at least, is still on the map—Wendover. Bert Wendover was an Oregonian whose doctor had estimated in about 1913 that he had only five years left to live. Bert decided to spend them alone beside the wild and beautiful Lochsa River, deep in the Bitterroot Mountains, living a long-cherished dream of his. Twenty years later he left his cabin, stronger and in better health than ever.[3]Bud Moore, The Lochsa Story: Land Ethics in the Bitterroot Mountains (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1996), 76.

Nez Perce Help

Another piece of the geographic puzzle of the Northwest fell into place, thanks to the Nez Perce chief’s cordiality. On 22 September 1805, Clark wrote, “I got the Twisted hare [hair] to draw the river form his Camp down which he did with great cherfullness on a white Elk skin, from the 1s fork [North Fork Clearwater] which is . . . seven miles below, to the large fork [Snake River] on which the So So ne or Snake Indians fish, is South 2 sleeps; to a large river [Columbia] which falls in on the N W. Side and into which The Clarks river empties itself is 5 Sleeps.” Clark’s grasp increased. All he had seen since leaving the Lemhi Shoshone at the end of August 1805 took on palpable shape. In today’s terms, both the Salmon River and the Clearwater River empty into the Snake; the Bitterroot and Clark Fork Rivers feed into the Columbia, and the two huge drainages, Snake and Columbia, join only seven or eight days’ travel from where he stood.

“Southing”

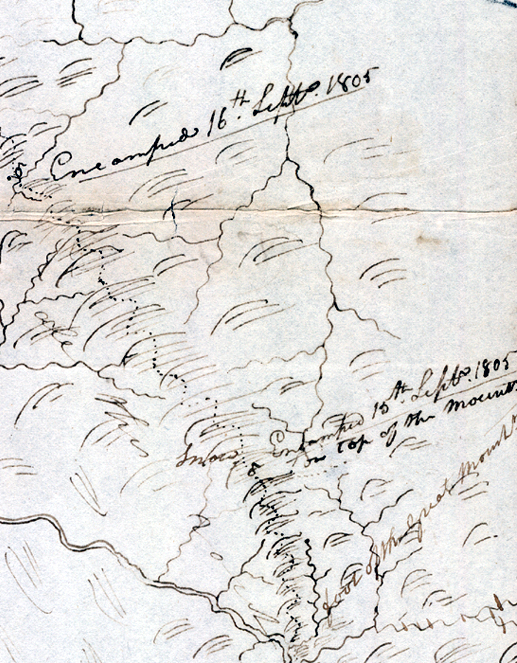

Near the top left edge of this map (Atlas, Map 70) Clark circled a note to himself, to draw his attention to it later. It reads: “from the Camp at the mouth of Travelers rest to the Indian Villages is too much West for the southing.” He evidently realized that his map of the road across the Bitterroot Range was out of proportion, that the east-west distance was too great relative to the north-south dimension. Perhaps his error can be explained by the absence from these maps (Atlas maps 69, 70, and 71) of the one-inch grid on which he usually plotted his charts. In Clark’s day the term southing meant “a course or distance south.”[4]Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (New Haven, Connecticut, 1806). It is not related to the terms “easting” or “northing,” which are modern terms denoting x-y grid references in USGS rectangular map coordinates.

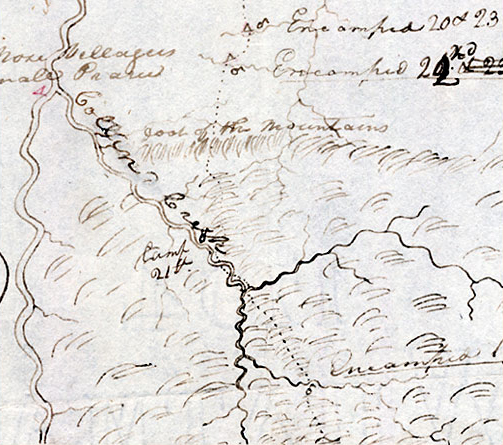

Moreover, Clark left no clue as to whether by “Indian Villages” he meant the two groups of summer lodges he had seen on Weippe Prairie, totalling about 30 double lodges, or the villages at the mouth of Collins (Lolo) Creek. However, inasmuch as those he first saw on the Clearwater at the mouth of Collins Creek represented the prime objective of the journey across the Bitterroots, and the resumption of the Corps’ voyage toward the Pacific Ocean, it seems logical to conclude that he meant the latter.

Perspectives

It was comparatively difficult for Clark to comprehend the lay of the land from the perspective of the dividing ridge he traversed from the Bitterroot Divide to Weippe Prairie. When he reached the high plateau and approached the Palouse country, he lost that point of view, and he made some misjudgments. For example, the stream here labeled “unknown” does not have any counterpart on modern maps. In terms of the distance from its mouth to the confluence of the North Fork with the Middle Fork of the Clearwater, it would appear to be Canyon Creek. But Canyon Creek is only 9 miles long, and does not have any tributaries; in fact, today it dries up by mid-summer. He may have confused it with the somewhat larger drainage today called Whiskey Creek, which is not represented on his map, but which joins Orofino Creek (his Rock Dam Creek) about three miles above the latter’s confluence with the Middle Fork of the Clearwater. There is no indication in the journals that he explored the Middle Fork himself, so here, more than likely, he relied on second-hand information from his hunters or, later, from Indian informants.

Sinque Hole to Dry Camp

17-18 September 1805

To see labels, point to the map.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. From Moulton, Atlas, Map 70.

Lolo Creek (Idaho)

Clark’s Map, 19–23 September 1805

To see labels, point to the map.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. From Moulton, Atlas, map 71.

Clearwater Country

22–22 September 1805[5]See also a detailed and highly instructive essay on the expedition’s Clearwater Canoe Camp Observations, by Robert N. Bergantino.

To see labels, point to the map.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Moulton, Atlas map 71, detail.

Map callouts reviewed by Norm Steadman.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert N. Bergantino, An Evaluation of Original Lewis and Clark Information to Determine the Location of Travelers Rest Camp, Lolo, Montana (1998). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Moulton, Journals, 5:237-40; 9:231-32; Atlas maps 69-71. Clark named Glade (today, Pack) Creek, Killed Colt Creek, Hungery Creek, Collins (Lolo) Creek, Village (Jim Ford) Creek, Rock Dam (Orofino) Creek, Cho-pun-nish (North Fork of the Clearwater) River, and Koos-koos-ke (Clearwater-Lochsa) River. |

| ↑3 | Bud Moore, The Lochsa Story: Land Ethics in the Bitterroot Mountains (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1996), 76. |

| ↑4 | Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (New Haven, Connecticut, 1806). |

| ↑5 | See also a detailed and highly instructive essay on the expedition’s Clearwater Canoe Camp Observations, by Robert N. Bergantino. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.