Clark and Evan Maps Compared

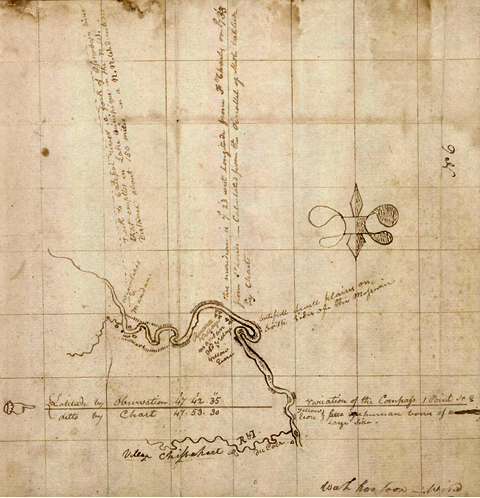

John Evans’s 1795 Map

Fort Mandan Area

To see labels, point to the image.

Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

It was late September 1796 when into the Knife River Indian Villages at “the very rim of European empire in the Americas,”[1]Gwyn A. Williams, The Search for Beulah Land: The Welsh and the Atlantic Revolution (London: Croom Helm, 1980), 118; quoted in W. Raymond Wood, Prologoue to Lewis and Clark: The Mackay and Evans … Continue reading stepped John Evans. Evans was a Welshman, and an assistant to Scotsman James Mackay. Both were from St. Louis, both were naturalized Spanish citizens, and both had been hired by the Spanish government to represent Spain’s right to displace British trading companies and maintain control of commerce in Upper Louisiana.

The most important material outcome of their expedition was a remarkably precise and detailed map of the Missouri River from St. Charles to the Mandan villages, which quickly was recognized as the most accurate made up to that time. Mackay, who had turned back at Fort Charles, the trading post he built on the Missouri somewhere between the mouths of the Platte and Niobrara rivers, drew the final version.

John Evans, who proceeded on upriver under Mackay’s orders to explore all the way to the Pacific Ocean, got no farther than the Knife River villages. He subsequently provided Mackay with six detailed maps of the river from Fort Charles to the Mandans, and a seventh from the Knife River to the Rockies based on Indian information he had gathered. The segment shown above is Evans’s No. 6. Thomas Jefferson acquired a copy of the complete map, which he sent to Lewis at Camp Dubois in January 1804. Lewis and Clark added only a few details of their own to the Evans-Mackay map of the lower Missouri. It is certain the captains had Evans’s seven maps also, since each contains one or more notes in Clark’s handwriting—in this instance “Village Chisschect” and “Wah hoo toon-Wind.”

Detail of Clark’s 1814 Map

Fort Mandan Area

To see labels, point to the image.

Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Lewis and Clark routinely made notes of Indian place-names, a laborious process that required careful translations of questions to insure correctness. Lewis recorded that the local name for the Miry River, with the same meaning, was E-pe,-Âh-zhah. Clark wrote Ches-che-ta as Chiss-Cho-tarr for the Heart River, indicating that he heard slightly different pronunciations of it. They left no record of Indian names for the Mouse River, which was widely known by its French name, Souris, which may have referred to its color. Nor did they ever write down an Indian name for the Knife River, so-called for the abundance of easily accessible flint along its banks, which Indians used for cutting tools and weapons. Nevertheless, the captains surely heard the Mandans call it Wahi Pasa Sh; the Hidatsas would say Miecci Aashi Sh or Mitis Adu Ash Sh; the Dakotas called it Isan Wakpa; the Lakota Sioux, Mina Wakpa. The French-Canadian engagés would have known it as Riviere de Couteau.[2]Marilyn Hudson, Administrator, Three Tribes Museum, New Town, North Dakota. Personal communication, 9 September 2006. During the Corps’ Long Camp on the Clearwater River in Idaho, the Nez Perce told the captains it wasWalch-Nim-mah. All meant the same thing: Knife River.

John Evans’s Map Validated

Validation

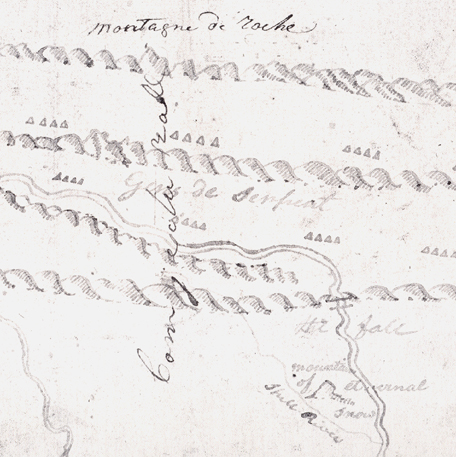

John Evans’s Map (detail)

To see labels, point to the map.

Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The word “Conjecturall,” in Clark’s handwriting, reflects either his own or Evans’s skepticism about the accuracy of Indian information concerning the Missouri River within the Rockies.

In January of 1804 Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis a copy of John Evans’s map.[3]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:163. It provided the captains with valuable information about the Missouri River from the vicinity of today’s Sioux City, Iowa, to the Mandan villages, where Evans concluded his exploration. It also contained a sketch of what the Indians at the latter place had told Evans about what lay beyond.[4]W. Raymond Wood, “The John Evans 1796-97 Map of the Missouri River,” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 1981), 39, 53. Jefferson’s cover letter is in Jackson, Letters, … Continue reading The above excerpt focuses on the point at which the Missouri River emerges from among the four mountain ranges that were then thought to comprise the Rockies. During the winter of 1804-1805 at Fort Mandan, Lewis compiled an extensive catalog of what he and Clark had learned about the Missouri, its tributaries and its sources, and appended a summary of what they were told they would find west of the Knife River villages.[5]Moulton, Journals, 3:362-367.

They could expect to pass the mouth of the Meé,-ah’-zah, or Yellowstone River about 235 straight-line miles up the Missouri. One hundred twenty direct-line miles “nearly S.W. of the Yellowstone, the Mah-tush,-ah-zhah, or Muscle shell river falls in on the S. side.” Actually, the latter distance is about 180 miles, and the direction is more nearly west-by-south, or only ten degrees south of west, an error that may have resulted from a minor misunderstanding about directions. In any case, the compass bearing was inconsequential since the explorers would be following the river wherever it went.Elsewhere in Discovering Lewis & Clark, see Indian Spatial Concepts, in Mapping Unknown Lands by John Logan Allen. Also The Rocky Mountains James P. Ronda, “‘A Chart in his Way’: Indian Cartography and the Lewis and Clark Expedition,” Great Plains Quarterly, 4 (Winter 1984), 43-53.

About 120 miles further a little to the S. of West, on a direct line, the great falls of the Missouri are situated.[6]Actually, it is about 150 miles, “on a direct line,” from the mouth of the Musselshell to the Great Fall. The following description is in Moulton, Journals, 3:367. This is discribed by the Indians as a most tremendious Cataract. They state that the nois it makes can be heard at a great distance. That the whole body of the river tumbles over a precipice of solid and even rock, many feet high; that such is the velocity of the water before it arrives at the precipice, that it projects itself many feet beyond the base of the rock, between which, and itself, it leaves a vacancy sufficiently wide for several persons to pass abrest underneath the torrent, from bank to bank, without weting their feet. They also also state there is a fine open plain on the N. side of the falls, through which, canoes and baggage may be readily transported. This portage they assert is not greater than half a mile, and that the river then assumes it’s usual appearance, being perfectly navigable.

Some of what Lewis and Clark heard from the Indians at Fort Mandan seemed to validate Evans’s report. From their conversations that winter, Clark concluded the distance to the landmark waterfall would be roughly 610 miles.[7]Ibid., 3:373-374. The rest added landmarks to help them measure their progress. All that remained was “ground-truthing.”

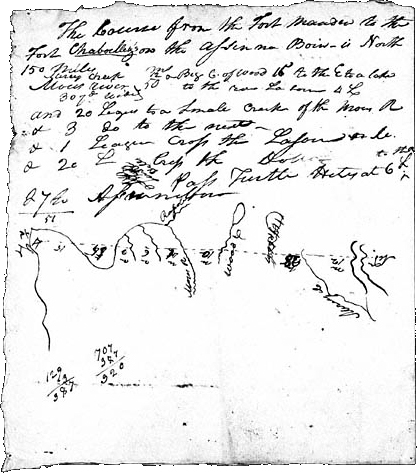

Souris River Trade Route

This map contains reminders and a sketch made by Lewis and Clark during their conversations with François-Antoine Larocque and other traders from the North West Company’s trading post, Fort Assiniboine, at the mouth of the Souris (Mouse) River.[8]See Larocque at Fort Mandan. It is difficult to make sense of some of the details, partly because several figures refer to miles, and others to leagues (3.0 statute miles, or 4.8 kilometers).

The manager, or bourgeois, at Fort Assiniboine was Charles Chaboillez, to whom Lewis and Clark sent a cautiously cordial letter via free trader Hugh McCracken on 31 October 1804. They informed Chaboillez that they were sent by the U.S. government “for the purpose of exploring the river Missouri, and the western parts of the continent of North America, with a view to the promotion of general science.” Lewis assured him of President Jefferson’s open border, free trade policy:

We shall, at all times, extend our protection as well to British subjects as American citizens, who may visit the Indians of our neighbourhood, provided they are well-disposed; this we are disposed to do, as well from the pleasure we feel in becoming serviceable to good men, as from a conviction that it is consonant with the liberal policy of our government, not only to admit within her territory the free egress and regress of all citizens and subjects of foreign powers with which she is in amity, but also to extend to them her protection, while within limits of her jurisdiction.[9]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents,1783–1854 (2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd ed., 1978), 1:213–14. The phrase … Continue reading

Chaboillez replied in due time, expressing “a great anxiety to Serve us,” Clark noted, “in any thing in his power.” The Canadian’s letter was delivered on 16 December 1804 (in 6 days—express mail, considering the severity of winter on the High Plains) by Hugh Heney, or Hené. We don’t know what the factor wrote, but we do know that the courier-trader made a hit with the captains, who, according to Larocque, “Enquired a great deal of Mr. Heney, Concerning the sioux Nation, & Local Circumstances of that Country & lower part of the Missouri, of which they took notes.”[10]W. Raymond Wood and Thomas D. Thiessen, Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 143. In fact, the illustration above may be the record of that conversation.

Lewis and Clark’s “Miry Creek” was a translation of Bourbeuse—”Miry”—by which Larocque knew it. In June 1805, Larocque recorded his own experience in fording it: “We unloaded our horses and crossed the property on our shoulders there being not more than 2 feet [of] water, but we sunk up to our middle in mud, the horses bemired themselves in crossing and it was with difficulty we got them over the banks being bogs as also the bed of the river.”[11]Ibid., p. 164. Later called Snake Creek, its lower 17 miles became part of Lake Sakakawea when Garrison Dam was completed in 1956.

Turtle Mountain, with its summit only 500 feet above the surrounding plain, is nonetheless the most conspicuous landmark in the vicinity. It is the centerpiece of the 3,118-acre (1,257 hectare) International Peace Garden, which straddles the 49th parallel, two thirds of it in Manitoba, the rest in North Dakota. It is not a mountain in the “Rocky” sense, but a heavily wooded mass of glacial drift. The area is dotted with many small lakes.[12]See Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest (reprint, 1956, 3 vols.; New York: Harper, 1897), 1:308n.

Sheheke’s Map

During the winter at Fort Mandan, Clark drew this sketch from information provided by the Mandan chief, Sheheke (Big White) who dined with the captains on 7 January 1805, and gave him “a Scetch of the Countrey as far as the high mountains, & on the South side of the River Rejone [Roche Jaune; Yellowstone].” Clark added, “he Says that the river rejone recves 6 small rivers on the s. Side, & that the Countrey is verry hilley and the greater part Covered with timber, Great numbers of beaver &c.” Gary Moulton has concluded that some of the tributaries were added to the map after Clark covered the route in 1806.[13]Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b.

The comprehensive map Clark compiled at Fort Mandan that winter shows “The War Path of the Big Bellies Nation” extending westward from the mouth of the Knife River and crossing the Yellowstone at the mouth of O’Fallon Creek (Coal Creek, or Oak-tar-pon-er). It is impossible to say whether this was supposed to be identical with the route shown on Sheheke’s map, because Clark drew both from Indian information before he explored the ground personally.

Notes

| ↑1 | Gwyn A. Williams, The Search for Beulah Land: The Welsh and the Atlantic Revolution (London: Croom Helm, 1980), 118; quoted in W. Raymond Wood, Prologoue to Lewis and Clark: The Mackay and Evans Expedition (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003), 129. Clarification of Evans’s copyist’s handwriting is also from Wood, pp. 146-49. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Marilyn Hudson, Administrator, Three Tribes Museum, New Town, North Dakota. Personal communication, 9 September 2006. |

| ↑3 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:163. |

| ↑4 | W. Raymond Wood, “The John Evans 1796-97 Map of the Missouri River,” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 1981), 39, 53. Jefferson’s cover letter is in Jackson, Letters, 1:163. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Journals, 3:362-367. |

| ↑6 | Actually, it is about 150 miles, “on a direct line,” from the mouth of the Musselshell to the Great Fall. The following description is in Moulton, Journals, 3:367. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 3:373-374. |

| ↑8 | See Larocque at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑9 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents,1783–1854 (2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd ed., 1978), 1:213–14. The phrase “serviceable to good men” may suggest that Lewis was consciously practicing the precepts of Freemasonry, an affiliation that is evidenced a number of times in his expedition journals. Back in Virginia, Lewis had risen quickly from Fellowcraft to Past Master Mason within the first four months of 1797. By October, 1799, he was a Royal Arch Mason, which represented the completion of the Master Mason’s degree. See on this site Lewis as Master Mason. |

| ↑10 | W. Raymond Wood and Thomas D. Thiessen, Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 143. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., p. 164. |

| ↑12 | See Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest (reprint, 1956, 3 vols.; New York: Harper, 1897), 1:308n. |

| ↑13 | Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.