we still beleive ourselves in the country

usually hunted by the Assinniboins.

we passed several old encampment of Indians . . .

of about 100 lodges who were progressing slowly

up the river; the most recent appeared to have been

evacuated about 5 weeks since. these we supposed

to be the Minetares [Gros Ventre] or black foot Indians

who inhabit the country watered by the Suskashawan.

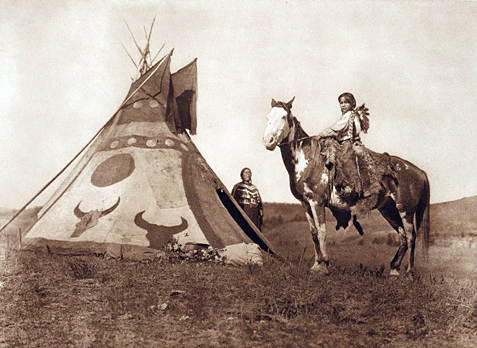

A Painted tipi—Assinboin, (undated)

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

The Chipewyan. The Western woods Cree. The Sarsi Vol. 18, Plate 633. Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

To Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Indians along the Upper Missouri were nearly invisible, their presence made palpable only through traces and remnants, signs and portents. For those Indians who made their homes in what is now northeastern Montana (the Gros Ventre, the Blackfeet People, the Assiniboines, the Crees, and Siouan Peoples), Euroamericans were not entirely alien. Assiniboine/Chippewa historian and storyteller Joseph McGeshick says, “The Assiniboine had been in contact with Whites for fifty years before Lewis and Clark . . . initially coming in contact with Frenchmen . . . working for the Hudson’s Bay Company.”[1]Joseph Robert McGeshick, “Joe McGeshick,” Turtle Island Storytellers Network website, http://wisdomoftheelders.org/category/tisn-montana/#post-513928.

In the late eighteenth century, too, the Assiniboines and Blackfeet had suffered the first of several devastating visitations of European diseases, against which they had little or no resistance. As Princeton historian Andrew Isenberg writes, “The rise of the nomadic, equestrian, bison-hunting Indian societies of the western plains was largely a response to [the] European ecological and economic incursion.”[2]Andrew C. Isenberg, The Destruction of the Bison (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 32.

Richmond Clow of The University of Montana elaborates:

The Plains culture was a relatively new mode of life for Indians and was an adaptation to the rapid expansion of colonial settlements. . . . The Plains culture lasted only about two centuries and does not characterize the way Indians lived for centuries before its emergence in the late 1700s. Before then . . . many of the Plains nations such as the Sioux belonged to cultures that were related to the farming and mound-building communities of the Mississippi Culture (a.d. 800 to 1500). Nevertheless the Plains cultures flourished during the 1700s and . . . much of the 1800s and lasted until U.S. authorities pacified the Plains Indians and placed them on reservations.[3]Richmond Clow, “Native Peoples of the Northern Plains,” Native America: Portrait of the Peoples, edited by Duane Champagne (Detroit: Visible Ink, 1994), 163.

After the Expedition

Chiefs of Montana

1882. © 1995-2007 Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, J. N. Choate, photographer, X-32151.

Group studio portrait of eight Native American men, chiefs of Montana (Piegan or Blackfeet), (identified with nine names), top row, from left to right: Running Crane, White Grass, Tail Feather, Coming Over the Hill, and Young Bear Chief; bottom row: Four Horses, Little Dog, White Calf, and Little Plume.

Among the last regions of Montana to be settled by Euro-americans, the Upper Missouri country was considered to be much less appealing than the territory’s mineral-rich areas and lush river valleys to the west. For this reason, beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux—then resident in the area.

University of Lethbridge historian Sheila McManus notes that, besides these tribes’ warlike reputations (especially that of the Blackfeet), their location—the Upper Missouri was far “removed from the major streams of white transcontinental movement”—contributed to their “late, rapid colonization.” McManus quotes Indian agent John Young: “No Indian tribes . . . have had so little intercourse with the whites in the past as the consolidated tribes of the Blackfeet, Bloods, and Peigans [sic]” because of the “out-of-the-way location of their reservation—no places of interest or importance requiring roads through it.”[4]Sheila McManus, The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2005), 59. The Young quotation is from U.S. Department of … Continue reading

During the 1850s, government Indian agents for the region operated out of Fort Union, at the confluence of the Missouri and the Yellowstone, and then out of Fort Benton, the head of navigation on the Missouri. At first, the only non-Indian settlements within the Upper Missouri were a handful of outposts devoted to the fur trade. The Assiniboine in particular vigorously participated in the fur trade, exchanging skins and furs for a variety of trade goods.

Stretching from the Canadian border to the Missouri, Montana’s northern tier gradually drew the interest of whites, and in increments, the United States government whittled away at the tribes’ homeland. In 1868, with the second Fort Laramie Treaty, the government established Indian agencies in the region—for the Blackfeet on the The Teton River north of Choteau (now known as the Old Agency) and for the rest of the tribes (Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Yankton Sioux, and River Crow) at the Milk River Agency, near present-day Chinook.

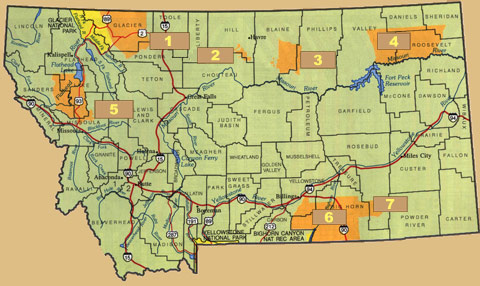

Finally, in 1888, the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Sioux, and Assiniboine relinquished their claim to 17.5 million acres (27,344 square miles) of their joint reservation in favor of three separate reservations. The Blackfeet reservation (1,462,640 acres; 2,285 square miles) was headquartered at Browning, just east of Glacier National Park; Gros Ventre and Assiniboine made their homes on the Fort Belknap Reservation (675,147 acres; 1,055 square miles); and several bands and divisions of the Assiniboine and Sioux Nations settled on the Fort Peck Reservation (2,174,000 acres; 3,397 square miles), with its headquarters at Poplar. The second, third, and fourth largest reservations in Montana (the Crow Reservation is the largest), these reservations remain today the homelands of these tribes. A fourth reservation—Rocky Boy’s—was created by Congress in 1916, as home to the Chippewa and Cree bands of Chief Rocky Boy. Located just south of Havre, it is, at 120,000 acres (187 square miles), the smallest of the four reservations in northeastern Montana.

European Diseases

Restriction to reservations was not the only factor in the shrinking of the Plains Indians’ world. From the 1770s on, multiple epidemics of smallpox, cholera, and other imported diseases had devastated their populations. As early as 1844, artist George Catlin asserted in his North American Indians, “The system of trade, and the smallpox, have been the great and wholesale destroyers of these poor people.”[5]George Catlin, North American Indians, edited by Peter Matthiessen (New York: Viking, 1989), 479.

Even after the smallpox epidemics of the late eighteenth century (in which both the Assiniboines and Piegans, for example, lost between half and three-fifths of their populations), the early nineteenth century brought further horrors. In mid-summer 1837, the steamboat St. Peter arrived at Fort Union, bearing trade goods and, undetected, the smallpox virus. The Assiniboine who brought bison hides to the post soon contracted the disease and carried it back to their people. Fur trader Edwin Thompson Denig reported that, of the Assiniboine who came to Fort Union that summer, fully 90 percent died—as many as 1,100 men, women, and children. Princeton historian Andrew Isenberg writes, paraphrasing Denig, “Those who died at the trading post were daily thrown in the river by the cartload. Those who fled the post fared no better. Lodges in which whole families lay dead lined the trails leading from Fort Union.” This epidemic lasted into 1840. Waves of smallpox further decimated the tribes of the Upper Missouri in 1848, 1856, and 1869-1870. It is believed that the population of all Plains tribes fell from a high of 142,000 in 1780 to 53,000 in 1890, in large part because of disease and starvation.[6]Isenberg, Destruction, 118; Denig’s account appears in Edwin Thompson Denig, Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri: Sioux, Arikaras, Assiniboines, Crees, Crows, edited by John C. Ewers … Continue reading

The impact of these events on tribal cultures was devastating. As Denig said of one tribal group after its encounter with cholera, “Their former good order and flourishing condition deranged, they are no more the same people.”[7]Quoted in Isenberg, Destruction, 120; original source, Denig, Five Indian Tribes, 19. After 1870 (and the last major smallpox outbreak), the Blackfeet—who had been the most feared warriors of the Northern Plains—were so weakened that they no longer represented a threat to Euro-american settlement.

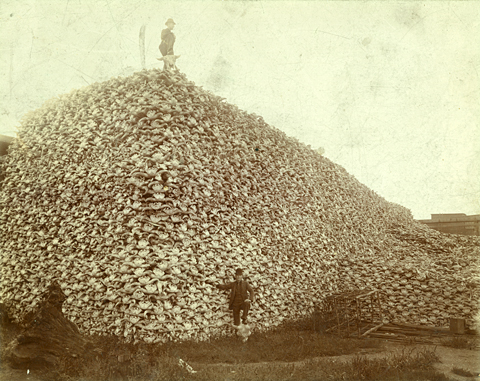

Bison Decline

At the same time, the annihilation of the great bison herds contributed greatly to undermining the Plains Indians’ nomadic way of life. The website for the Inter-tribal Bison Cooperative (an effort by fifty-seven tribes to reintroduce the bison) declares, “The destruction of buffalo herds and the associated devastation to the tribes disrupted the self-sufficient lifestyle of Indian people more than all other federal polices to date.”[8]“Our History,” Inter-tribal Bison Cooperative website, http://itbcbuffalo.com/node/3. While there is considerable debate among historians about the various factors that led to the eradication of the bison, it is clear that, with the disappearance of the bison, the impact on the Indians of the Northern Plains was irrevocable. By all accounts, market hunters had destroyed the last major bison herds on the Upper Missouri by 1883.

Well before that, the reduction of bison herds had begun to affect the health of some tribes. In his history of the destruction of the bison, Andrew Isenberg writes:

In the winter of 1846, an Indian agent on the Missouri reported that the Assiniboines of the northern plains were reduced to starvation. They subsisted for a time on deer, elk, and wolves, but these were either too few or too insubstantial to sustain them. After consuming their reserves of dried meat, berries, and roots, they fell upon their own dogs and horses.[9]Isenberg, Destruction, 112.

Without the bison to hunt, and with the populations of other game species depleted by over-hunting, the Indians of northeastern Montana found themselves increasingly dependent on the federal government. Mismanagement and corruption by Indian agents led to more tragedies. Government rations were inadequate and often late, and in 1882, 600 Blackfeet died of starvation and exposure, and in the winter of 1883-1884, 300 Assiniboine starved to death on the Fort Peck Reservation.

The Dawes Act

1. Blackfeet Confederacy (Pikuni/Piegan, North Piegan Pikuni, Blood/Kainai, and Blackfoot Siksika); 2. Rocky Boy’s (Chippewa-Cree); 3. Fort Belknap (Gros Ventre and Assiniboine); 4. Fort Peck (Assiniboine and Sioux); 5. Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (Bitterroot Salish, Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai); 6. Crow (Abs·alooke); 7. Northern Cheyenne (Northern Cheyenne Tribe).

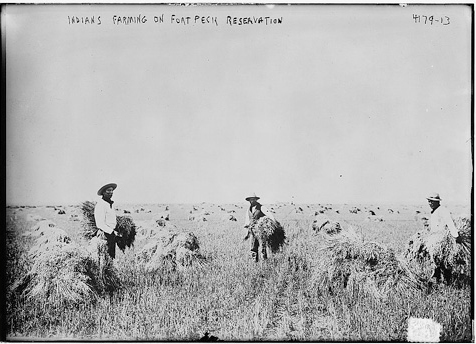

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Allotment Act, which while it may have been well-intentioned, led to further losses of territory for most of the tribes. Scholars disagree about the motivations behind passage of the act. Some believe that western speculators sought to open more land to white development; others assert that the act was fueled by eastern reformers who “deeply believed that communal landholding was an obstacle to the civilization they wanted the Indians to acquire,” and had little faith in the government’s ability “to protect the tribal reservations from the onslaught of the whites,” thereby leaving the Indians without any landholdings at all.[10]Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 669. For a thorough discussion of the Dawes Act, see E. A. Schwartz, “What Were the Results of … Continue reading

With the intention of making Indian people self-sufficient through agriculture, the Dawes Act granted 160 acres of reservation land to every Indian head of family, 80 acres to single people over eighteen and orphans under eighteen, and 40 acres to single people under eighteen. The government later allowed non-Indians to purchase the reservation lands not allotted. As scholar Jeanne Oyawin Eder, an enrolled member of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of Fort Peck, writes, this further breaking down of tribal homelands “continues to anger many Indians.” A history of the Fort Peck tribes notes:

Finally, the Congressional Act of 30 May 1908, commonly known as the Fort Peck Allotment Act, was passed. The Act called for the survey and allotment of lands now embraced by the Fort Peck Indian Reservation and the sale and dispersal of all the surplus lands after allotment. Each eligible Indian was to receive 320 acres of grazing land in addition to some timber and irrigable land. Parcels of land were also withheld for Agency, school and church use. Also, land was reserved for use by the Great Northern (Burlington Northern) Railroad. All lands not allotted or reserved were declared surplus and were ready to be disposed of under the general provisions of the homestead, desert land, mineral and townsite laws.

Today, on the Fort Peck Reservation, 395,893 acres are tribally owned; individual tribal members own a total of 509,602 allotted acres; and non-Indians own 1,268,505 acres.[11]Jeanne Oyawin Eder, “‘OH-P; SHE-DU WOK-PAH’ (Muddy Waters): Montana Indians in the Twentieth Century,” Montana Century: 100 Years in Pictures and Words, ed. Michael P. Malone … Continue reading

Leonard Carlson, in his book, Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land, writes that the Dawes Act had six primary goals: to “break up the tribe as a social unit, encourage individual initiative, further the progress of Indian farmers, reduce the cost of Indian administration, secure at least part of the reservation as Indian land, and open unused lands to white settlers.” While the promotion of farming among the Indians was a stated goal, historian E. A. Schwartz notes that “on a majority of reservations, the amount of land required for allotment under the Dawes Act far exceeded the amount of tillable land” and the government offered little assistance to the Indians in their transition to an agriculture-based economy. And just like other homesteaders, Indian farmers often found that 320 acres were simply not enough to sustain a family farm in this arid land. Schwartz concludes:

What was most significant about Indian policy after the Dawes Act was not that it forced more Indians to become assimilated. . . Perhaps what was most significant was precisely what had been most significant during the four centuries before the Dawes Act: the continuing loss of Indian lands.[12]Leonard A. Carlson, Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land: The Dawes Act and the Decline of Indian Farming (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1981), 3; Schwartz, “What Were the Results of … Continue reading

Water Rights

One bright spot for the new Indian agriculturalists, at least in the long term, had to do with access to water. In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court established, in its decision in Winters v. United States, that Indian tribes have a “reserved” water right that has precedence over most other rights and does not need to be exercised in order to be retained. The Winters Decision originated from a case brought against the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine Indians on the Fort Belknap Reservation and having to do with water rights on the Milk River.

In the spring of 1905, reservation superintendent William R. Logan reported, “We have had no water in our ditch whatever. Our meadows are now rapidly parching up. The Indians have planted large crops and a great deal of grain. All this will be lost unless some radical action is taken to make the settlers above the Reservation respect our rights.”[13]Quoted in Norris Hundley, Jr., “The ‘Winters’ Decision and Indian Water Rights: A Mystery Reexamined,” Western Historical Quarterly, January 1982, 20.

In an unprecedented move, the Justice Department asked a judge to issue a restraining order against the non-Indian settlers upriver, forbidding them from diverting Milk River water if such diversion interfered with the water needs of the Fort Belknap Reservation. The affected settlers filed suit to overturn the restraining order, and after traveling through the lower courts, the case reached the nation’s highest court. The Supreme Court upheld the judge’s order, but refused to determine a “specific and permanent volume” as the tribes’ right. This landmark decision would take many decades to sort out, but it did firmly establish that most U.S. Indian tribes possessed permanent water rights and gradually, over the next century, in final determinations of these rights for many tribes, including those on the Upper Missouri.[14]Hundley, “The Winters’ Decision,” 36.

Indoctrination

Educational efforts to further assimilate Indian peoples were often aimed at stripping away tribal cultural traditions and, especially, languages. A federal commission noted in 1868, “In the difference of language to-day lies two-thirds of our trouble. . . . Schools should be established, which children should be required to attend; their barbarous dialects should be blotted out and the English language substituted.” This attitude resulted in efforts to convert the Indians of northeastern Montana to Christianity, outright banning of such traditions as the Sun Dance, and the sending of Indian children to boarding schools far from home.[15]Quoted in J. D. C. Atkins, “‘Barbarous Dialects Should Be Blotted Out . . .’: Excerpts from the 1887 Report of the ëCommissioner of Indian Affairs,” … Continue reading The president of the Native American Bar Association, Richard Monette, has said:

Native America knows all too well the reality of the boarding schools where recent generations learned the fine art of standing in line single-file for hours without moving a hair, as a lesson in discipline; where our best and brightest earned graduation certificates for homemaking and masonry; where the sharp rules of immaculate living were instilled through blistered hands and knees on the floor with scouring toothbrushes; where mouths were scrubbed with lye and chlorine solutions for uttering Native words.[16]Quoted in Andrea Smith, “Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools,” Amnesty International Magazine (Summer 2003), http://www.amnestyusa.org/node/87342.

Recovery and Renewal

Darrell Robes Kipp received the 2005 Montana Governor’s Humanities Award in recognition of his role as co-founder of the Browning-based Piegan Institute and Nizipuhwahs (Real Speak) Center, which focuses on language immersion for Blackfeet students from kindergarten through eighth grade.

Despite poverty, alcoholism, and other related social ills, these losses of tradition and language need not be irretrievable. As poet M. L. Smoker, an enrolled member of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, writes:

What are we native to? All along

I have said it was the landscape and the language

wrought there according to wind and need.

But I have begun to change my opinion, not of where

and who I come from, but of how

we might establish a particular resonance:

As in coyotes and stones and the full

relationship between thought and deed.

The “fantastik” we all might choose—if given the chance—

to name ourselves over again.[17]M. L. Smoker, “Call It Instinct,” Another Attempt at Rescue (New York: Hanging Loose Press, 2005), 52-53.

Assiniboine/Gros Ventre/Chippewa educator and poet Minerva Allen, in a 1989 interview with oral historian John Terreo, championed the teaching of traditional Indian culture and language as a kind of inoculation against the dangers and seductions of modern life. “There are surveys now,” she told Terreo, “saying that the kids or Indian adult students who kept their traditional values tend not to go into drugs and alcohol. And . . . the kids that have not been raised in the traditional way or have not been involved with parents who are really responsible, they tend to lose their identity.”[18]Minerva Allen as interviewed by John Terreo, “Minerva Allen: Educator, Linguist, Poet,” The Montana Heritage: An Anthology of Historical Essays, edited by Robert R. Swartout and Harry W. … Continue reading

In a collection of folktales she compiled, Allen recounts a cautionary tale, “Ring Tail” (named after a relatively recently adopted round dance). The anonymous narrator says:

This old fellow went out looking for his horses. . . . I guess he fell asleep on the side of a hill, and there was a bunch of prairie chickens dancing over on top the hill. . . One of them came down. That was his dream. This prairie chicken came down and sang one song to him. He caught the song right away. . . . that next day was to be a big dance. Fourth of July down at the Agency. Nobody believed him. Just him and his wife use to dance that. All around here, these people would laugh at him. He told these people, “What I’m doing is going all over the world, this dance.” By golly, he told the truth. It did go all over the world. . . Yeah, he fell asleep on this side of a hill, and there was a bunch of prairie chickens dancing on top of the hill and one of them came and gave him this dance.[19]Minerva Allen, Stories by Our Elders: The Fort Belknap People (Lodge Pole, MT: Hays/Lodge Pole Public Schools, 1983), 149-150.

This tale can be seen as a parable that precisely delineates the challenges that Indian people face today, expressing the value of staying attentive to traditional ways—and at the same time, underscoring the need to remain open to innovation within a living tradition.

Just as powwow dancing has taken Indian people around the globe, so have self-directed educational efforts and cutting-edge entrepreneurial initiatives aided the Indian peoples of northeastern Montana in their drive to reinvent identities and retain cultures. Cultural leaders like Minerva Allen on the Fort Belknap Reservation and Darrell Robes Kipp, founder of the Piegan Institute on the Blackfeet Reservation, have done a great deal to make this happen. So have tribally owned businesses like A&S Diversified (A&S stands for Assiniboine and Sioux) on the Fort Peck Reservation, with its commitment to “demonstrating the ever-expanding capabilities of the Fort Peck economic community.”[20]http://www.fortpecktribes.org/. By teaching traditional ways and native languages, by looking both forward and backward, these leaders have made an enormous difference. At Fort Belknap College, they call this “Weaving Traditions and Technology.”

The creation of tribal colleges in the 1980s reinforced the trend toward self-education, and this process was hastened in 1990, when Congress passed the Native American Languages Act, which asserts “the status of the cultures and languages of native Americans is unique and the United States has the responsibility to act together with Native Americans to ensure the survival of these unique cultures and languages.”[21]For full text of the Native American Languages Act, see http://www.nabe.org/Resources/Documents/Legislation%20page/NALanguagesActs.pdf. Meanwhile in Montana, the Indian Education for All legislative initiative included monies for the research, writing, and publication of full histories of each tribe in the state, further emphasizing the importance of Indian peoples’ unique contributions to the culture of the state and the nation.

For northeastern Montana’s Indian peoples, the past two hundred years have been challenging, at best, and often brutally destructive, but the future—because of these inspiring tribal educational and economic initiatives—begins to look decidedly brighter.

Notes

| ↑1 | Joseph Robert McGeshick, “Joe McGeshick,” Turtle Island Storytellers Network website, http://wisdomoftheelders.org/category/tisn-montana/#post-513928. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Andrew C. Isenberg, The Destruction of the Bison (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 32. |

| ↑3 | Richmond Clow, “Native Peoples of the Northern Plains,” Native America: Portrait of the Peoples, edited by Duane Champagne (Detroit: Visible Ink, 1994), 163. |

| ↑4 | Sheila McManus, The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2005), 59. The Young quotation is from U.S. Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, 47th Congress, 1st Session, 169. Young served as agent to the Blackfeet from 1876 until he resigned eight years later. |

| ↑5 | George Catlin, North American Indians, edited by Peter Matthiessen (New York: Viking, 1989), 479. |

| ↑6 | Isenberg, Destruction, 118; Denig’s account appears in Edwin Thompson Denig, Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri: Sioux, Arikaras, Assiniboines, Crees, Crows, edited by John C. Ewers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961). |

| ↑7 | Quoted in Isenberg, Destruction, 120; original source, Denig, Five Indian Tribes, 19. |

| ↑8 | “Our History,” Inter-tribal Bison Cooperative website, http://itbcbuffalo.com/node/3. |

| ↑9 | Isenberg, Destruction, 112. |

| ↑10 | Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 669. For a thorough discussion of the Dawes Act, see E. A. Schwartz, “What Were the Results of Allotment?” on the Native American Documents Project website, California State University, San Marcos, http://public.csusm.edu/nadp/asubject.htm. |

| ↑11 | Jeanne Oyawin Eder, “‘OH-P; SHE-DU WOK-PAH’ (Muddy Waters): Montana Indians in the Twentieth Century,” Montana Century: 100 Years in Pictures and Words, ed. Michael P. Malone (Helena, MT: Falcon Publishing, 1999), 65; Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Community Profile. |

| ↑12 | Leonard A. Carlson, Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land: The Dawes Act and the Decline of Indian Farming (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1981), 3; Schwartz, “What Were the Results of Allotment?” |

| ↑13 | Quoted in Norris Hundley, Jr., “The ‘Winters’ Decision and Indian Water Rights: A Mystery Reexamined,” Western Historical Quarterly, January 1982, 20. |

| ↑14 | Hundley, “The Winters’ Decision,” 36. |

| ↑15 | Quoted in J. D. C. Atkins, “‘Barbarous Dialects Should Be Blotted Out . . .’: Excerpts from the 1887 Report of the ëCommissioner of Indian Affairs,” http://www.languagepolicy.net/archives/atkins.htm. |

| ↑16 | Quoted in Andrea Smith, “Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools,” Amnesty International Magazine (Summer 2003), http://www.amnestyusa.org/node/87342. |

| ↑17 | M. L. Smoker, “Call It Instinct,” Another Attempt at Rescue (New York: Hanging Loose Press, 2005), 52-53. |

| ↑18 | Minerva Allen as interviewed by John Terreo, “Minerva Allen: Educator, Linguist, Poet,” The Montana Heritage: An Anthology of Historical Essays, edited by Robert R. Swartout and Harry W. Fritz (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1992), 237. |

| ↑19 | Minerva Allen, Stories by Our Elders: The Fort Belknap People (Lodge Pole, MT: Hays/Lodge Pole Public Schools, 1983), 149-150. |

| ↑20 | http://www.fortpecktribes.org/. |

| ↑21 | For full text of the Native American Languages Act, see http://www.nabe.org/Resources/Documents/Legislation%20page/NALanguagesActs.pdf. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.