The practice of collecting Indian vocabularies was well-established prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Above is a detail from an extensive Indian vocabulary from a 1791 book by J. Long. The digital image was made from a book in the Jefferson Library.[2]J[ohn] Long, Indian trader, Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians . . . (London: Robson, et al., 1791), p. 198.

The tragic and premature death of Meriwether Lewis is again realized, this time, in relation to the Indian vocabularies he had so carefully collected while on the historic journey to the Pacific coast. Due to the many unfortunate events which followed Lewis’s death, in 1809, the vocabularies are now lost, and were never made available to the public.

Commercial Importance

When President Jefferson made his request to Congress for authority and appropriations for the Missouri River and Pacific Northwest exploring expedition, it was based on the belief that the North American Indian held the key to a successful expansion of the United States.[3]Ibid., pp. 10–13. In fact, Congress agreed to an appropriation for such an expedition with the understanding that its purpose would be to establish a commercial relationship with the Indians.

Basic to this relationship would be a means of communicating ideas with the various tribes. It was, therefore, of necessity that the leaders of the expedition diligently collect vocabularies of all the natives that they encountered. Indeed, Captain Lewis “. . . was very attentive to this instruction, never missing an opportunity of taking a vocabulary.”[4]Ibid., p. 611.

Twenty-three vocabularies were collected[5]Ibid., p. 486. The number of vocabularies forwarded to Clark from the personal effects of Lewis. This the author supposes is the complete number of vocabularies collected, as it is also the number … Continue reading forming a document of primary importance. Considering the purpose for which the Congress had authorized the expedition, this document ranks as one of the most significant papers of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It has been lost for over 170 years, and perhaps was never seen by more than a half dozen people. It is doubtful that such a document would ever have been willfully discarded, and there is a good chance that it may still exist somewhere in the collections of papers in private or public archives.

Jefferson’s Instructions

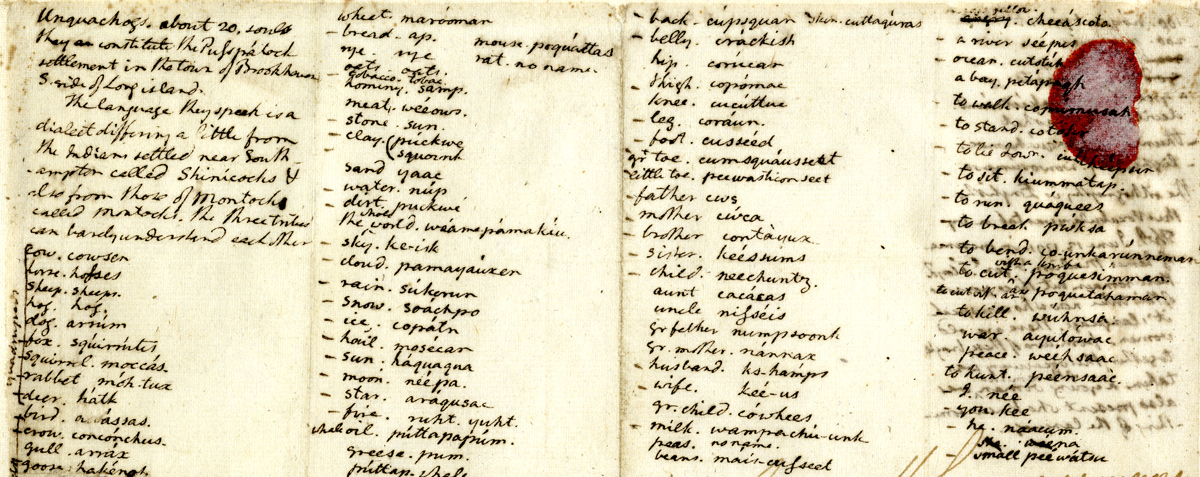

Vocabulary of the Unquachog Indians [Detail]

Thomas Jefferson, “Vocabulary of the Unquachog Indians,” APS Museum Online Collections, accessed January 24, 2023, exhibits.amphilsoc.org/sarah-manning-vaughan/items/show/108.

Three fragments of Jefferson’s Indian vocabularies pulled from the James River are available for viewing at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. The Unquachog Vocabulary above is written in Jefferson’s hand.

Four months after Congress passed the legislation authorizing what was to become known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, President Jefferson wrote a list of instructions for Captain Lewis regarding objectives of the enterprise. In part, he wrote:

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, & such principal stream of it, as, by it’s course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce . . . .

The commerce which may be carried on with the people inhabiting the line you will pursue, renders a knolege of those people important.[6]Ibid., pp. 61.66. Also reproduced in: Thwaites, R. G., editor, Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Dodd Mead & Co., N. Y., 1904. Vol. 7, Appendix XVIII, pp. 247-252.

And so, even with his own “great design” for the mission, i.e. contributions to science and a quest for a transcontinental water route, Jefferson was compelled to adhere to the fundamental purpose of the expedition, that of establishing good relationships with the Indians, which were to serve both the Native Americans and the American people. Among the items on his list of requirements for the expedition, Lewis included “Blank Vocabularies.”[7]Ibid., p. 70. These were ” . . . a number of printed vocabularies of the same words and form . . . with blank spaces for Indian words.”[8]Ibid., p. 611.

Genealogical Motivations

In addition to collecting vocabularies for the purpose of better understanding the Indian language for communication reasons, there was at that time a strong belief, especially among Americans, that it would be possible to connect the ancestry of the American Indians with that of the Europeans and Asians through linguistics.[9]The many proposed theories of the relationship between the American Indians and the Old World inhabitants becomes an interesting study in itself. The earliest attempt to connect the two (so far as … Continue reading John Evans (whose maps and writings about the Missouri River as far upstream as the Mandans were used by the captains) was a Welshman who had come to America in search of the fabled “Welsh Indians”, a supposedly lost colony of Welsh who had come to America in the fourteenth century and were never heard of again.[10]Also of interest in the matter of the “Welsh Indians” is that information found in George Catlin‘s Letters and Notes on the North American Indians, London, 1841. Catlin not only set … Continue reading Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, who helped train Lewis for the expedition, was “particularly curious” on the subject of Indian vocabularies and occasionally published material on the subject.[11]Jackson, op. cit., p. 289, note. In 1806 Dr. Benjamin Barton wrote an article for the Philadelphia Medical and Physical Journal, in which he said that he found the relation of the Osage Indian … Continue reading Jefferson, himself, was keenly interested in this subject and while he was still president had collected vocabularies of 250 words from several tribes. He compared these with various 130-word vocabularies of the great Russian languages, and found 73 to be common.[12]Ibid., p. 465. Jefferson suffered a great loss in 1809, when his belongings were being moved from Washington to Monticello—the trunk which carried his Indian vocabularies was stolen. The thief … Continue reading

Jefferson’s Copies

Lewis had collected 14 Indian vocabularies by 7 April 1805. These, he packed up and shipped back to President Jefferson via the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) on its downriver return from Fort Mandan. From the Mandan country to the Pacific Ocean, Lewis continued to collect vocabularies, and upon his return to St. Louis in September 1806, he wrote to Jefferson stating that he had collected nine more.[13]Ibid., p 323.

Jefferson’s plan was to take all the vocabularies he had collected from tribes east of the Mississippi River (about 40 of them) and add these to the vocabularies which had been collected by Lewis west of that river. In April 1816, in a letter to Jose Correa da Serra, Jefferson wrote:

. . . the intention was to publish the whole, and leave the world to search for affinities between these and the languages of Europe and Asia.

However, Jefferson was burdened with other work and didn’t get around to carrying out his plan before Lewis began assembling the writings and journals of the expedition. Lewis, therefore, asked the president for permission to publish the expedition’s vocabularies separately. The president consented.[14]Ibid., p. 611.

Attempts to Publish

The purpose of Lewis’s trip east in October 1809, during which he lost his life, was in part related to the publishing of his writings. The prospectus of his forthcoming work, which had been published two years earlier, showed that his plan was to publish “. . . a comparative view of twenty-three vocabularies of distinct Indian languages, procured by Captains Lewis and Clark on the voyage . . . .” These Indian vocabularies were to be printed in the second part of his two-part, three volume work—the part “. . . confined exclusively to scientific research . . . .”[15]Ibid., pp. 394-396.

Lewis had his writings with him at the time of his death, together with many other personal and public belongings. The month following his death these effects were dispersed to various individuals and governmental departments. Clark received the material which pertained to the Expedition, among which he found “. . . one bundle of vocabulary.”[16]Ibid., pp. 470-472. The burden of getting all the papers ready for publication now fell entirely upon the co-commander of the exploring enterprise.

On the second of January 1810, Clark set out for Philadelphia to arrange for the editing and publication of the expedition’s written material.[17]Ibid., p. 486. The next month he contacted Nicholas Biddle, a young Philadelphia lawyer and litterateur, for the purpose of soliciting him to edit the expedition’s journals.[18]Ibid., p. 494. It was not until March 17, 1810, that Biddle finally accepted the task.[19]Ibid., p. 496.Ibid., p. 598. Having conscientiously labored fifteen months on the narrative, and receiving not one cent for his efforts, Biddle wrote to Clark stating that: “I am content that … Continue reading

In the spring of that same year, Biddle was in Virginia going over the journals and interviewing Clark, preparing for the long laborious editing task before him.[20]Ibid., p. 497. At this time he received from Clark “. . . papers and documents which would be necessary for the publication of the travels.”[21]Ibid., p. 635. Reported to have happened, in this manner, in a letter written by Nicholas Biddle to William Tilghman in 1818. Among these “papers and documents” was material for Dr. Barton, who had, prior to this time, been employed to publish the scientific data for the “Travels.”[22]Ibid., p. 488. Biddle did not closely examine the materials intended for Dr. Barton, but recalled later that the Indian vocabularies were among them. He wrote: “They formed, I think a bundle of loose sheets each sheet containing a printed vocabulary in English with the corresponding Indian name in manuscript. There was also another collection of Indian vocabulary, which if I am not mistaken, was in the handwriting of Mr. Jefferson.” Biddle returned to Philadelphia from Virginia and “immediately” forwarded the scientific data to Dr. Barton.[23]Ibid., p. 636.Ibid., p. 465. The Indian vocabularies “. . . in the handwriting of Mr. Jefferson,” were undoubtedly the fourteen vocabularies which had been sent to the president from Fort … Continue reading On this matter, Dr. Barton assured Jefferson that the papers placed in his custody would be taken care of. He wrote: “. . . assure you, and beg you, Sir, to assure his [Lewis’s] friends, that they will be taken care of; that it is my sincere wish to turn them, as much as I can, to his honour & reputation; and that they shall ultimately be deposited in good order in the hands of General Clark, or those of Mr. Conrad, the publisher.”[24]Ibid., p. 561.

Unfortunately such good intentions did not materialize. Not only had Dr. Barton failed to begin work on the expedition’s scientific data before his death in 1815,[25]Ibid., p. 614. but he also left his “. . . immense heap of papers . . .” in such a deplorable disorder that the many people with proper claim to the books and papers became a tremendous burden upon his widow.[26]Ibid., p. 608. However, Mrs. Barton seems to have cooperated as well as could be expected considering the condition of her late husband’s papers, and Jefferson received from her three of the traveling pocket journals.[27]Ibid., p. 615.

Jefferson Steps In

In September 1816, Jefferson, no longer a public official, wrote to Clark requesting authority in his name to collect the Indian vocabularies and other scientific material which he believed to be in the possession of Nicholas Biddle, “. . . with a view to have these given to the public according to the original intention.” His plan was to deliver the “. . . the Papers of Natural History and the Vocabularies to the Philos. Society [The American Philosophical Society], at Philadelphia, who would have them properly edited, . . .” and the originals put away for safe keeping.[28]Ibid., p. 619.

Clark, too, must have been of the opinion that Biddle had the vocabularies in his possession. He wrote to Biddle asking that they be turned over to Jefferson.[29]Ibid., pp. 623-624. He also sent a letter of authorization to Jefferson, which would enable him to collect the papers of the expedition in his (Clark’s) name. Jefferson did not promptly act upon this authority given him by Clark in October 1816, but held off, while waiting for a new Secretary of War to be appointed. When writing to John Vaughan on 28 June 1817, Jefferson indicated: “. . . that office having some rights to these papers.”[30]Ibid., p. 631. After a delay of some months awaiting the appointment, Jefferson proceeded to accumulate the papers without the help of the War Office.

A Lost Cause?

In April 1818, Biddle deposited with the Historical Committee of the American Philosophical Society the material in his possession. He explained in detail, through a letter to a William Tilghman (evidently the committee chairman), what the bundle of Indian Vocabularies looked like, as well as how they were delivered to Dr. Barton in the early summer of 1810. He added: “I have mentioned the particulars so minutely because the description may perhaps enable some of the Committee to recognize the vocabularies, which I incline to think were the only things delivered by me to Dr. Barton not included in the volumes now deposited [in the Philosophical Society].”[31]Ibid., pp. 635-636.

As late as 1826, we find Clark still inquiring as to the whereabouts of the vocabularies, believing that they must still be in the possession of the executors of Dr. Barton.[32]Ibid., p. 644.

Mrs. Barton had inadvertently allowed an agent of Thomas Jefferson to take a volume of botanical notes not relating to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Jefferson was so kind as to return this journal.[33]Ibid., p. 633. It is possible that Mrs. Barton also, in error, released the Indian vocabularies to the wrong party, who was not as considerate as Jefferson, and rather than returning them, discarded them! But it seems more likely that this valuable documentation still is extant, hidden beneath piles of unsorted papers, and under the “protection” of some unsuspecting archivist “back east”, and may some day be found, and receive all the study that Jefferson and Lewis and Clark hoped for.

Notes

| ↑1 | Bob Saindon, “The Lost Vocabularies of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, We Proceeded On, July 1977, Volume 3, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol3no3.pdf#page=4. Bob has requested the editor to point out to readers that “A substantial amount of material for this article has been compiled from letters, documents and notes published in Donald Jackson’s Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1785–1854, Univ. of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1962.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | J[ohn] Long, Indian trader, Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians . . . (London: Robson, et al., 1791), p. 198. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., pp. 10–13. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., p. 611. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., p. 486. The number of vocabularies forwarded to Clark from the personal effects of Lewis. This the author supposes is the complete number of vocabularies collected, as it is also the number Lewis mentions in his prospectus, which will be mentioned shortly. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., pp. 61.66. Also reproduced in: Thwaites, R. G., editor, Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Dodd Mead & Co., N. Y., 1904. Vol. 7, Appendix XVIII, pp. 247-252. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., p. 70. |

| ↑8 | Ibid., p. 611. |

| ↑9 | The many proposed theories of the relationship between the American Indians and the Old World inhabitants becomes an interesting study in itself. The earliest attempt to connect the two (so far as this author can ascertain) was in 1607, in a volume written by a Gregorio Garcia, titled: Origen de los Indios dei Nuevo Mundo, e Indios Occidentales (Origin of the New World and Western Indians), published in Valencia, Spain. Many books have been published on the subject through the years, but without a doubt, the one published in 1830, by Joseph Smith, Jr. (“Author and Proprietor”), titled: The Book of Mormon, despite its obvious inaccuracies, has by far gained the greatest popularity. |

| ↑10 | Also of interest in the matter of the “Welsh Indians” is that information found in George Catlin‘s Letters and Notes on the North American Indians, London, 1841. Catlin not only set up a provocative argument relating to the apparent geographical movement of the Mandan Indians, but also developed a table of comparative words showing ten Mandan words which were very similar to the Welsh words of the same pronunciations and meanings. Both Sergeant John Ordway and Private Whitehouse, in their journal entries for September 5-6, 1805, when discoursing about the strange guttural speech or brogue of the Flathead [Salish] or Ootlashoot Indians in the Bitterroot Valley (present southwest Montana), allude to the nomenclature “Welch Indians”,. Regarding this, see: Quaife, Milo M., Editor, The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway, The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, 1916, second printing 1965, p. 282; Thwaites, op. cit., (Whitehouse Journal), Vol. pp. 150–151; Thwaites, Ibid. Vol. 3, p. 53, fn. 3. |

| ↑11 | Jackson, op. cit., p. 289, note. In 1806 Dr. Benjamin Barton wrote an article for the Philadelphia Medical and Physical Journal, in which he said that he found the relation of the Osage Indian language very striking to the Finnic, both of Europe and Asia. Ibid., pp. 463-464. We also find that in 1809, Barton wrote to Mr. Jefferson asking for a few words from the vocabularies collected by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Barton was in the process of publishing a new edition of “. . . my work on the dialects of the American Indians.” |

| ↑12 | Ibid., p. 465. Jefferson suffered a great loss in 1809, when his belongings were being moved from Washington to Monticello—the trunk which carried his Indian vocabularies was stolen. The thief broke into the trunk, and finding the papers containing the vocabularies of no value to him, threw them into the James River. Only worthless fragments were found. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., p 323. |

| ↑14 | Ibid., p. 611. |

| ↑15 | Ibid., pp. 394-396. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., pp. 470-472. |

| ↑17 | Ibid., p. 486. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., p. 494. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., p. 496. Ibid., p. 598. Having conscientiously labored fifteen months on the narrative, and receiving not one cent for his efforts, Biddle wrote to Clark stating that: “I am content that my trouble in the business should be recompensed only by the pleasure which attended it, and also by the satisfaction of making your acquaintance which I shall always value.” |

| ↑20 | Ibid., p. 497. |

| ↑21 | Ibid., p. 635. Reported to have happened, in this manner, in a letter written by Nicholas Biddle to William Tilghman in 1818. |

| ↑22 | Ibid., p. 488. |

| ↑23 | Ibid., p. 636. Ibid., p. 465. The Indian vocabularies “. . . in the handwriting of Mr. Jefferson,” were undoubtedly the fourteen vocabularies which had been sent to the president from Fort Mandan. It would appear that when Lewis decided to publish the vocabularies rather than Jefferson, as had been the original plan, Jefferson made a copy of Lewis’s original and sent off the copy to Lewis. This would also mean that Lewis’s original was among those thrown into the James River as footnoted previouslyante. |

| ↑24 | Ibid., p. 561. |

| ↑25 | Ibid., p. 614. |

| ↑26 | Ibid., p. 608. |

| ↑27 | Ibid., p. 615. |

| ↑28 | Ibid., p. 619. |

| ↑29 | Ibid., pp. 623-624. |

| ↑30 | Ibid., p. 631. |

| ↑31 | Ibid., pp. 635-636. |

| ↑32 | Ibid., p. 644. |

| ↑33 | Ibid., p. 633. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.