The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled by John Vaughan in Philadelphia.

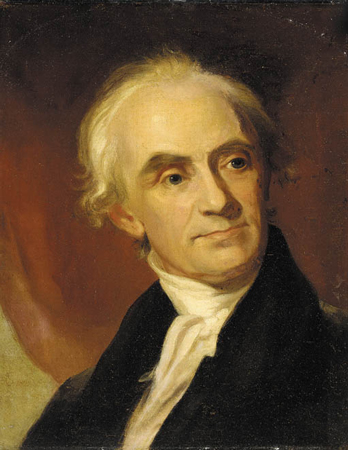

John Vaughan (1756–1841)

by Thomas Sully (1783–1872)

Oil on canvas, painted between 1815 and 1823. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery.

John Vaughan’s success as a wine merchant enabled him to contribute generously to the construction of Philosophical Hall. He also cataloged the Society’s library and was especially interested in Native American ethnology and linguistics.

—KKT, ed.

John Vaughan’s Donation Book

When Thomas Jefferson forwarded Lewis and Clark’s scientific specimens to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, they were registered by the Society’s librarian, John Vaughan, upon their arrival. But peculiarly, that one register was only for the shipment of materials sent by the explorers from Fort Mandan in 1805; it was never expanded. The rest of the collections that came in after the end of the expedition were either entered into another register—one not found now—or else they were re-distributed to their respective researchers without anyone formally recording their arrival.

The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled for the Lewis and Clark materials received in November 1805.[1]“Lewis & Clark Expedition Donation book containing a list of dried leaves &c. collected in the far West by Meriwether Lewis,” American Philosophical Society (Manuscripts Coll., … Continue reading A separate section was devoted to geological specimens, which noted several fossils[2]See the fully transcribed list in Moulton, Journals, 3:473-478. all but one of which are missing now. We point out that many, if not most, of the collections were passed along to the researchers who were then examining the expedition’s treasures, and thereafter the specimens were absorbed into personal or other institutional collections, the original data lost.[3]The rocks and minerals, for example, were given to Adam Seybert, a member of the American Philosophical Society and preeminent American mineralogist. He retained the specimens in his collection. When … Continue reading

The “Donation Book” entries were sequentially numbered by Vaughan, who seems to have transcribed notations that were written by Meriwether Lewis in the field. We can be reasonably certain of this because the text for item no. 9, the fossil fish jaw found by Sgt. Gass, is nearly identical to the text on the label that had accompanied the specimen. To some of Vaughan’s entries an identification has been added, presumably by Vaughan from personal observation or from some later communication received by him.

The Fossil List

The following accounting lists all of the fossil specimens known to have been received in Philadelphia; the numbers are Vaughan’s itemization in the register, which seems to reflect only the order in which the specimens were unpacked. The numbers omitted from this list are associated with items other than fossils.

7 Petrefaction on the Missouri May 30, 1804

On this date the expedition traveled some 14 miles on the Missouri River in the vicinity of today’s Portland, Missouri. It had rained heavily during the day and previous night, another indication that the inclement weather may have serendipitously exposed specimens for the explorers passing by.

9 a Petrified Jawbone of a fish or some other animal found in a Cavern a few miles distant from the Missouri S side of the River. 6 Aug. 1804, found by Searjant Gass

This is the specimen of Saurocephalus lanciformis, the sole known survivor of Lewis and Clark’s fossils.

24 Carbonated wood found on the Std side of the Riv near fort Mandane 60 feet above high water mark in the Bank Strata 6 Inch thick.

This item, together with nos. 64 and 66, are the only indications of paleobotanical material collected by the expedition. Just what the appearance was of these specimens is impossible to know, hence any hope of identifying them from their descriptions is gone. However, references to “carbonated wood” very probably indicate a black, carbonized form of wood such as the kinds familiar to paleontologists who collect in many formations of Cretaceous age.

39 Petrefactions obtained on the River ohio in 1803

The locale could have been anywhere between Pittsburgh and the Mississippi River, of course, but this otherwise testifies to Lewis’s observations of natural history at work even before the formal explorations began. There is also a possibility that these could have been additional specimens that Lewis had collected at Big Bone Lick.

59 A Specimen of calcareous rock, a thin Stratum of which is found overlaying a soft Sand rock which makes its appearance in many parts of the bluffs from the entrance of the River Platte to Fort Mandon. [Added later by Adam Seybert: “Mass of Shells.“]

This may be the only record of invertebrate fossils collected by the expedition. From this description, however, it is impossible to know whether they were marine or freshwater organisms, or whether they were collected from a very fossiliferous horizon or from a formation that had been formed from coquina, which is essentially a “hash” of shell material such as sometimes found in coastal plain environments.

“60 Found on the River Bank 1[?] Aug. 1804 (petrified [blank] nest)”

If the collection date was on 1 August 1804, the expedition had camped at Council Bluffs.[4]Moulton, Journals, 2:432-435. What was meant by a “petrified nest” of any kind is difficult to guess. A possibility is that it was in fact a nest, which had been encrusted by calcium carbonate, or travertine, if it occurred in the vicinity of a tributary of heavily mineralized water.

“64 Specimen of Carbonated wood with the loose sand of the sand-Bars of the Missouri & Mississipi, it appears in considerable quantaties in many places.” [Seybert: “carbonated wood.“]

“66 Found in the Bluffs near Fort mandan.” [Seybert: “Petrefied wood.“]

In addition to these specimens, several more entries in the “Donation Book” are noted without any kind of identifying characteristics. Some of these could have been fossils as well, but which will never be known. It is possible that fragments of William Clark‘s “fish rib” (the possible dinosaur bone mentioned earlier) may have been among the unspecified materials registered by Vaughan, but this, too, will never be known unless the specimens are fortuitously re-discovered.

Selected Specimens

July 15, 1804

Treeless plains

After waiting for the Missouri River fog to lift, the expedition sets out at 7 am and encamps near present Nemaha, Nebraska. Lewis’s chronometer stops, and he collects a specimen of hedge bindweed.

May 30, 1804

Another fourteen miles

Lost hunter Joseph Whitehouse and his boat and crew of engagés join the main group late at night. In the morning, Clark records the incident. Lewis collects a specimen of River-bank grape, Vitis riparia.

May 27, 1804

Gasconade River

The flotilla meets two trading parties coming down from Omaha and Osage villages. At evening camp near the mouth of the Gasconade River in present Missouri, arms and ammunition are inspected.

May 25, 1804

Last 'White' village

The expedition reaches La Charrette—the last settlement of “white people on this River . . . .” Here the captains meet trader Régis Loisel who shares valuable information about where they are going.

June 14, 1804

Gobbling snakes

The morning is foggy as the boats leave the Grand River, and they make only eight miles up the Missouri. They meet four traders loaded with furs, and Drouillard hears snakes that gobble like turkeys.

June 16, 1804

Unwanted passengers

The men use ropes to pull the barge against a current full of roiling sand making camp near present Waverly, Missouri late in the day. Clark says that the mosquitoes and ticks are numerous and bad.

June 3, 1804

Mosquitoes and ticks

At the mouth of the Osage, mosquitoes and deer ticks vex Clark, and Lewis collects a specimen of ground plum. Late in the day, the boats move up to the mouth of the Moreau east of present Jefferson City.

July 27, 1804

Leaving White Catfish Camp

At White Catfish Camp, the boats are loaded, and they proceed to present Lewis and Clark Landing in Omaha, Nebraska. A knee is cut, mosquitoes rage, and Lewis adds several plants to his collection.

August 17, 1804

Otoe chiefs and a deserter

At Fish Camp near present Homer, Nebraska Pvt. Labiche informs the captains that three Otoe chiefs and the deserter Pvt. Reed will soon arrive. A prairie fire is set as a signal to any nearby Indians.

July 13, 1804

Favorable winds

Favorable winds push the boats over twenty miles up the Missouri River. They encamp west of Corning, Missouri. Lewis collects a specimen of white sage, but otherwise the day appears uneventful.

July 30, 1804

Council Bluff arrival

The expedition arrives at a bluff at present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska where they intend hold a council with the Otoes. Pvt. J. Field kills a badger, and Lewis preserves it as his first zoological specimen.

May 10, 1804

First plant specimen

At winter camp on the present Wood River in Illinois, the enlisted men are ordered to carry 100 lead balls for their rifles. In St. Louis, Lewis collects the expedition’s first plant specimen.

May 22, 1804

Trading with Kickapoo hunters

After a very rainy night, the expedition sets out at 6 am, travels 18 miles, and camps near the mouth of the Femme Osage River in present-day Missouri. They trade with some Kickapoos for four deer.

July 20, 1804

Drouillard is sick

The expedition passes Water-which-Cries and Waubonsie creeks along the present Nebraska and Iowa border. Lead hunter George Drouillard is sick, and Lewis collects two specimens of clover.

June 1, 1804

Mouth of the Osage

After a hard day, the expedition stops at the mouth of Osage River where the captains make celestial observations late into the night. Lewis also collects a specimen of wild ginger, Asarum canadense.

July 18, 1804

Geology and botany

Clark remarks on the region’s geology and Lewis collects a partridge pea specimen as they travel up the Missouri below present Nebraska City. At their evening camp, a stray Indian dog is fed.

August 4, 1804

Moses Reed is missing

The expedition travels 15 miles and encamps southwest of present Modale, Iowa. The captains record yesterday’s speech to the Otoes, and Pvt. Moses Reed, who left to retrieve his knife, does not return.

May 29, 1804

A lost hunter

The expedition spends most of the day at the mouth of the Gasconade River drying goods and waiting for Joseph Whitehouse to return from a hunting trip. Lewis prepares a plant specimen of Golden Seal.

August 1, 1804

A botanist's field day

At present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, Clark prepares a peace pipe anticipating that the Otoes will soon arrive for a council. Two men search for lost horses and others search for the Otoes.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Lewis & Clark Expedition Donation book containing a list of dried leaves &c. collected in the far West by Meriwether Lewis,” American Philosophical Society (Manuscripts Coll., 917.3 L58). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See the fully transcribed list in Moulton, Journals, 3:473-478. |

| ↑3 | The rocks and minerals, for example, were given to Adam Seybert, a member of the American Philosophical Society and preeminent American mineralogist. He retained the specimens in his collection. When the Academy of Natural Sciences was founded, in 1812, the collection was purchased by a member of the Academy and donated to that institution. The original catalogues (Seybert’s original and an 1825 recataloging by him) are in the Archives of the Academy, and they note about three dozen specimens attributed to “Capt. Lewis.” However, only a few specimens are identified with any certainty today as having come from the Lewis and Clark expedition, even though the Seybert Collection remains in the special cabinet built for it in 1825. For an overview, see Earle E. Spamer et al., “A National Treasure: Accounting for the natural history specimens from the Lewis and Clark expedition (western North America America, 1803-1806),” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, vol. 150 (2000), 47-58. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, Journals, 2:432-435. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.