“Much of the daily work of the two captains was inspired by a set of transcendental values grouped under the rubric of Enlightenment philosophy—to observe, describe, and name all the universe’s constituent elements.”

The Dictionary of Bias-Free Usage remonstrated that “only by a strange twist of white ethnocentrism can one be considered to ‘discover’ a continent inhabited by millions of people.” Political correctitude might suggest that we simply drop the word discovery from our Lewis and Clark lexicon, and just speak of the captains as explorers.

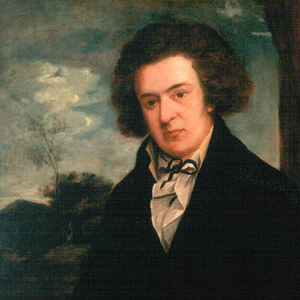

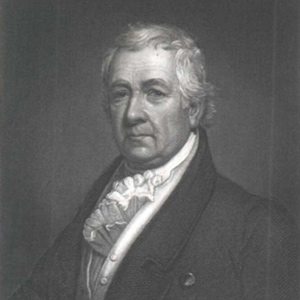

Caspar Wistar

Philadelphia mentor

When Lewis met him, Wistar was an eminent physician and professor—popular with his students, beloved by his patients. In 1811, he completed and published the first volume of A System of Anatomy for the Use of Students of Medicine.

President Jefferson naturally was curious about weather conditions in the newly acquired expanse of Louisiana, and weather observations were on the long list of assignments for his exploring team. Jefferson instructed Lewis to record climate data observed on the trip.

In this brief extract from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Carol MacGregor explains the beginning and purpose of the American Philosophical Society and its connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

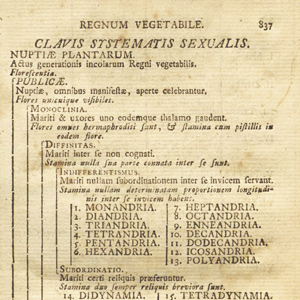

In 1758, the great Swedish classifier Carl Linnaeus urged every scientist to give join him in using a universal and simplified system of classification. He had just published a new text re-naming every plant and animal he knew with a two-word Latin label—a binomial.

For Meriwether Lewis, the theory of extinction was a philosophical argument, not a foregone conclusion. He might even have wondered how he would deal with a live mastodon if he came across one.

In Cuvier’s time, the idea of extinction was entertained, but it was still in dispute. What was most difficult to ascertain was what extinction meant in understanding the history of the earth.

It is not difficult to imagine Jefferson—who probably witnessed the flight—just a few years later contemplating another kind of adventure and recalling those days of excitement and tragedy in Philadelphia.

The Academy’s monumental collection of scientific specimens includes the Lewis and Clark Herbarium, consisting of most of the botanical specimens the Expedition brought back East.

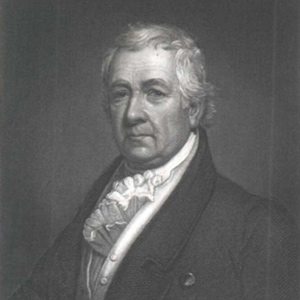

Ellicott was one of the best surveyors of his time, renowned today for the accuracy of his work. He was appointed Surveyor General of the United States in 1792. Ellicott’s personal history was particularly applicable to the mission at hand.

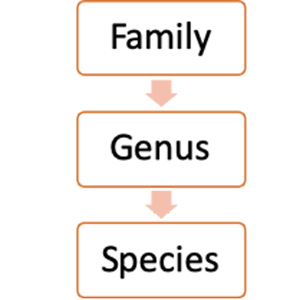

The science of the orderly classification of all living and extinct organisms is called taxonomy. It comprised a hierarchical outline of descriptors extending between the most general and the most specific and Lewis and Clark had a role.

Thomas Jefferson and the A.P.S.

by Carol Lynn MacGregor

Thomas Jefferson’s leadership of the fledgling American Philosophical Society was appropriate. His perspective was entirely the same as its stated purposes, and his contributions to it have continued to enrich and guide it.

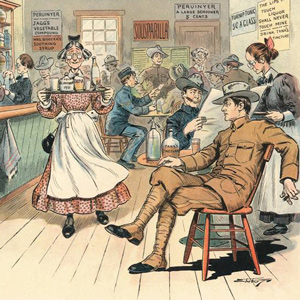

Treatment emphasized depletion of ‘morbid excitement’ through bleeding and purging. Calomel and jalap were preferred purgatives; blended together they became Rush’s pills, taken along by the Corps of Discovery.

Even in Lewis and Clark’s day, new species were being classified using a system developed by naturalist Carl Linnaeus.

No more calomel! Not just an anthem, a reflection on the transition from the “Age of Enlightenment” to the “genteel tradition.”

Important for the history of the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, its first plant specimens were consigned to Barton’s care. Here began the disassembling of the collection, and his promised volume on natural history was never written.

Rush’s Writings for the A.P.S.

A list of Rush’s writings for the American Philosophical Society (from Lyman H. Butterfield, “Benjamin Rush as a Promoter of Useful Knowledge,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 92, no. 1, March 1948, 35-6.)

Early American Entomology

by Joseph A. Mussulman

There were only four notable 18th century naturalists who showed much interest in America’s insects: a young Englishman named Mark Catesby, Finnish botanist Peter Kalm, Philadelphian William Bartram, and Reverend Frederick Melsheimer of New Hampshire.

We may never know the full historical impact of Lewis and Clark’s discoveries upon nineteenth-century scientific inquiry, but this example highlights how just a series of conversations with the returning explorers allowed a significant earth science discovery to be revealed to the scientific community.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.