Public domain image based on a portrait by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827). Digitization made possible by a lead gift from The Polonsky Foundation.

Wilkinson’s Pet Project

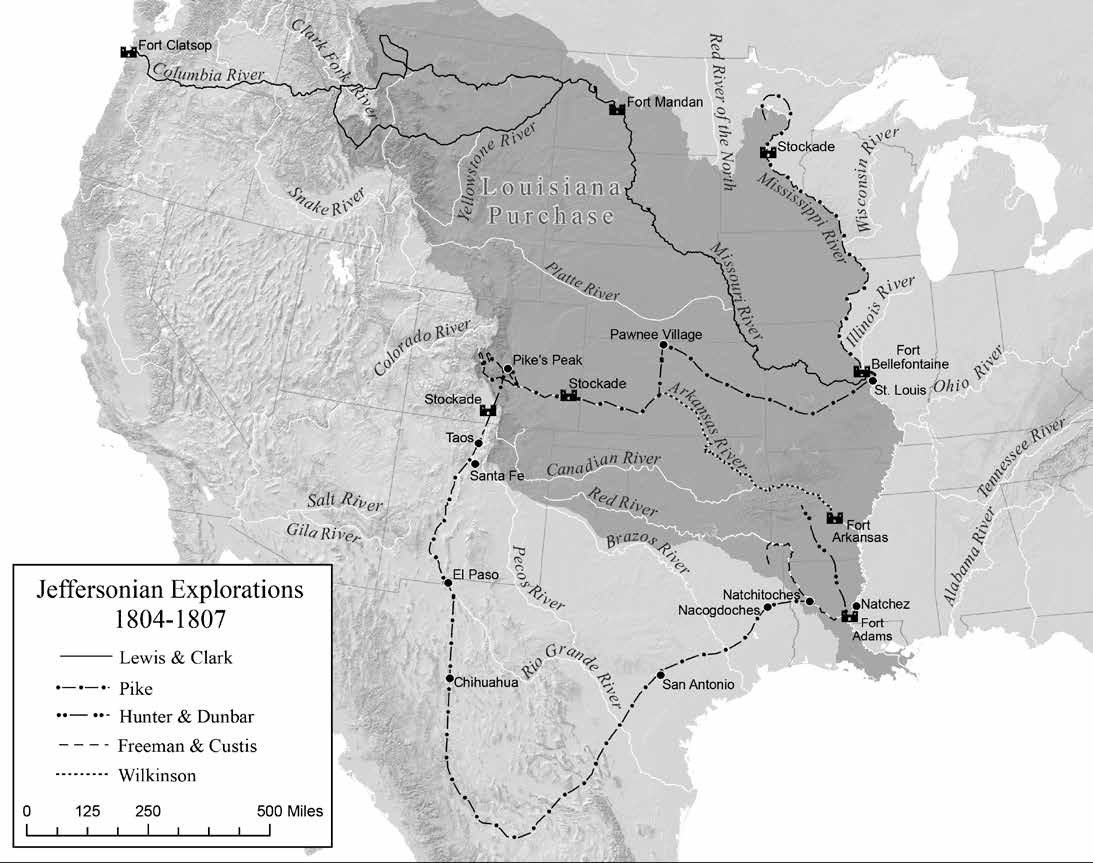

While Thomas Jefferson dispatched his personal secretary Meriwether Lewis to explore the Missouri and his scientist friend William Dunbar to explore the Ouachita, General James Wilkinson formulated exploration plans of his own, turning to Zebulon Montgomery Pike—a New Jersey soldier raised as an army brat and Wilkinson’s protégé. Pike enlisted in the army at age fifteen and by 1799 had risen to the rank of first lieutenant and was stationed at Fort Kaskaskia, located on the Mississippi River some fifty miles south of St. Louis, where he served under Wilkinson. Pike was there during the first week of December in 1803 when Lewis and Clark came to the fort to recruit a dozen soldiers for their expedition. Because they were not seeking officers, however, he was not a candidate to accompany them.

Unlike Jefferson, Wilkinson did not solicit congressional approval or funding prior to sending forth his own expedition. Acting under his own prerogative as military commander, he conveyed army merchandise and supplies to Pike to cover the expedition’s expenses. Wilkinson’s instructions to Pike, issued in St. Louis, directed him to proceed “up the Mississippi with all possible diligence . . . until you reach the source of it” while charting the river’s course, soil types, and climatic information. Wilkinson told him to seek out the Native Americans, noting populations, fur-trading preferences, tribal territory, and information on their neighbors—vital information that could be used to the United States’ advantage in controlling and occupying the region. The winter expedition was also an excellent time to check on the fur trade and warn British traders that trespassed on U.S. soil. Finally, Wilkinson admonished Pike to keep a diary of all his observations.[1]Wilkinson to Pike, 30 July 1805, in Donald Jackson, ed., The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, with Letters and Related Documents, 2 vols. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 1:3–4. … Continue reading

Up the Mississippi

Pike set out from Fort Bellefontaine on 9 August 1805, with twenty enlisted men in a “Keel Boat 70 feet long”. They proceeded upriver while Pike made scientific observations, recorded journal entries, and compiled maps. After they reached present Minnesota, shallow water forced them to use smaller boats. Establishing winter quarters and leaving Sergeant Kennerman in charge, Pike set out on 10 December 1806 with eleven others pulling two sleds and two canoes across the snow and ice. On 1 February 1806, Pike incorrectly identified Leech Lake (instead of Lake Itasca, some twenty-five miles distant) as the source of the Mississippi, 2,320 miles from New Orleans.

Pike met with Hugh McGillis of the British North West Fur Company, who treated him with great hospitality and a veritable feast. To McGillis’s dismay, Pike told him to lower the Union Jack and replace it with the stars and stripes, asserting U.S. sovereignty. Pike tried, unsuccessfully, to have an Indian delegation return home with him. He was, however, able to parley with a party of Dakota Sioux, offering them $2,000 in wares for a nine-mile tract of land to be used for a U.S. military post—the site of future Fort Snelling. Upon returning to his winter camp, he found that Sergeant Kennerman had presumed the worst and had rifled through Pike’s personal belongings, emptied the larder, and consumed all the whiskey. Instead of shooting him, Pike demoted him to a private and, in late February, the party began its homeward journey. After traveling nearly 5,000 miles in nine months, Pike arrived back in St. Louis on 30 April 1806. He immediately went to work to compile his reports, observations, and journals.[2]Pike, “Journal of the Mississippi River Expedition,” in Donald Jackson, ed. The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike: With Letters and Related Documents (Norman: University of Oklahoma … Continue reading

Exploring the Southwestern Boundaries

Several months before the Burr conspiracy imploded, Wilkinson embarked upon another one of his schemes while two of Jefferson’s exploring teams remained in the field: Freeman and Custis were on their way up the Red River about to be turned back by the Spanish; Lewis and Clark were in Montana on their return journey. It was time for Wilkinson to act. During the spring and summer of 1806, Burr assembled his private army for a filibuster while the general gathered military intelligence and sought ways to provoke the Spanish to declare war. Pike, who was probably not privy to Burr and Wilkinson’s intrigues, received word that Wilkinson had given him a new assignment: to explore the central and southern Great Plains to the Continental Divide to help define the southern limits of the Louisiana Purchase boundary between the United States and Spain.[3]It is unclear whether Wilkinson directed Pike to deliberately trespass on Spanish territory in order to be arrested so that Pike could have an opportunity to observe Spanish military strength. … Continue reading

For this expedition, Wilkinson instructed Pike to perform several tasks. First, as his primary objective, he was to deliver fifty-one Osage men, women, and children back to their village. Then, he was to broker peace between the Kansa and Osage nations and to meet with other tribes such as the Pawnees and, especially, the Comanches, to open discourse and trade with them. Because Pike’s journeys would likely take him to “the Head Branches of the Arkansaw, and Red Rivers” near the “settlements of New Mexico,” Wilkinson cautioned him to avoid Spanish contact to “prevent alarm or offence.” Finally, in his spare time, Pike was to collect geographical and scientific information and to ascertain the navigability of the Arkansas and Red rivers.[4]Wilkinson to Pike, 24 June 1806, in Jackson, Journals of Pike, 1:285–87. The Colorado Springs Pioneer Museum contains many of Donald Jackson’s research notes and papers and is especially rich … Continue reading

In a follow-up letter, Wilkinson authorized Pike to arrest “any unlicensed traders in your route . . . without a proper licence or passport” and to confiscate their property. On 15 July 1806, just six weeks after returning from exploring the Mississippi, Lieutenant Pike (whom Jefferson promoted to captain a few months later while Pike was on his Southwestern expedition) left Fort Bellefontaine in two river boats, escorted by twenty soldiers, interpreter Antoine Baronet Vasquez, surgeon John Robertson, and the general’s son, Lieutenant James Biddle Wilkinson. Most of the men with him, a group Pike once referred to as a “Dam’d set of Rascals,” had accompanied him up the Mississippi.[5]Wilkinson to Pike, 12 July 1806, in Jackson, Journals of Pike, 1:288–89. Pike’s journal of the western expedition commences on page 290 and concludes on page 448. Jay H. Buckley, “Pike … Continue reading

Pike’s Spanish Arrest

After dropping off the Osages in present Kansas, Pike continued to the Pawnee villages, convincing them to take down their Spanish flag and raise an American one. Pike’s party then turned south, traveling via horseback to the Arkansas. The party divided; Lieutenant Wilkinson took five men and descended the Arkansas River, while Pike and fifteen others ascended the Arkansas to the Colorado Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. Leaving his men in base camp in late November, Pike and three others attempted to climb what later became known as Pike’s Peak, but they were unable to do so because of the wintery conditions and deep snow.

Pike contented himself with exploring the headwaters of the South Platte and Arkansas rivers. With a dozen of his men suffering from frostbite, on 14 January 1807, Pike set out with those who could travel and, seeking the headwaters of the Red, crossed the Sangre de Cristo Mountains through a terrible blizzard and waist-deep snow. Pike built a small stockade on the Conejos River (a tributary of the Rio Grande near present Alamosa, Colorado), which he may have mistakenly thought was the Red.

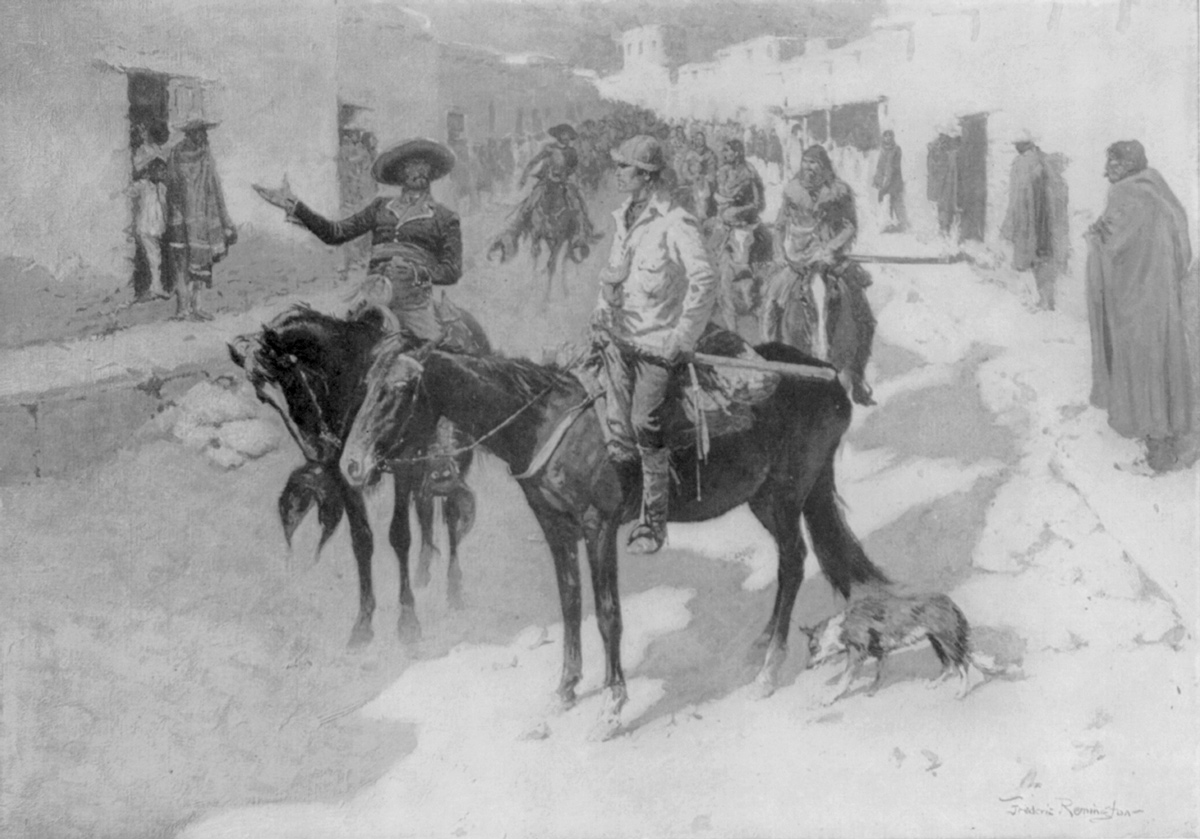

Pike granted permission for Dr. John Robinson to travel to the Spanish settlements. Alerted to the Americans’ presence by the arrival of Robinson, Facundo Melgares led a Spanish patrol who found and arrested Pike and his men on 28 February 1807, and escorted his American prisoners to Santa Fe, where Joaquin del Real Alencaster confiscated Pike’s papers.[6]Pike’s notes and papers were discovered in the Mexican archives by Herbert Eugene Bolton, who published them in the American Historical Review in 1908. Herbert E. Bolton, ed. “Papers of … Continue reading

Pike’s Ignoble Return

The Spanish treated Pike relatively well and marched him and his men to Chihuahua for questioning by General Nemesio de Salcedo. Then, traveling along the Old San Antonio Road through Coahuila, Pike finally arrived at Natchitoches on 1 July 1807. Whether or not Wilkinson intended for Pike to spy on the Spanish, Pike’s tour of the Spanish provinces in northern Mexico nonetheless provided Wilkinson with important details about the towns and their defenses. Although Jefferson and the War Department approved Pike’s exploration retroactively, to Pike’s great disappointment, he did not receive the hero’s welcome accorded Lewis and Clark, and neither he nor the members of his expedition received extra pay nor land as rewards for their efforts, because Congress suspected his complicity with Wilkinson and Burr.[7]Current information (unless new evidence surfaces to the contrary) indicates that Pike did not know of Wilkinson and Burr’s plot and remained a loyal American patriot.

Pike was exonerated of all charges of complicity in the Burr conspiracy and, more important, re-created an informative and detailed report from memory and published his journals and maps in 1810. Like Lewis and Clark, he provided information on flora and fauna and discovered several new species, but in contrast to the illustrious duo, Pike’s southern exploration paved the way for a viable route linking the United States and Santa Fe.[8]Nicholas King rendered a hastily prepared version of Pike’s Mississippi route and maps in late 1806 or early 1807. Donald Jackson, ed., The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, with Letters and … Continue reading While some criticize errors in his maps and journals and his limitations in scientific inquiry, Pike’s materials made an important contribution to understanding the Mississippi River, its tributaries, and the geography of the southern plains. Their publication contributed to the development of the Santa Fe trade and American expansion into the Southwest.

Pike continued serving under Wilkinson and secured Mississippi Governor William C. C. Claiborne’s recommendation that he be appointed Governor of Florida if the United States annexed it. Colonel Pike commanded troops in West Florida stationed at Baton Rouge and was called upon to remove intruders in the neutral territory between the Arroyo Hondo and the Sabine River in 1812. After the United States declared war on Great Britain on 18 June 1812, Brigadier General Pike led a successful attack on York (Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada, in 1813, only to be fatally wounded by flying debris when a powder magazine exploded during that engagement. His life is immortalized in the name Pikes Peak, which he approached but did not summit.[9]Clarence E. Carter, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 9, Territory of Orleans, 1803–1811 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940), 909, 927–28, 998–1001; … Continue reading

Further Reading

For a brief biography and document set relating to Pike, see Jay H. Buckley and Jeffery D. Nokes, “Chapter 2: Zebulon Pike’s Expeditions, 1805–1807, and Pike’s ‘Dissertation of Louisiana,’ 1808.” In Explorers of the American West: Mapping the World through Primary Documents, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016. Pages 38–71.

For Pike’s relationship with Thomas Jefferson, James Wilkinson, Aaron Burr, Lewis and Clark, the Spanish, and others, see Matthew L. Harris and Jay H. Buckley, eds., Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012).

Notes

| ↑1 | Wilkinson to Pike, 30 July 1805, in Donald Jackson, ed., The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, with Letters and Related Documents, 2 vols. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 1:3–4. Historians estimate the expedition’s expenses at around $2,000. Biographies include W. Eugene Hollon, The Lost Pathfinder: Zebulon Montgomery Pike (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1949); John Upton Terrell, Zebulon Pike: The Life and Times of an Adventurer (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1968); John M. Hutchins, Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike Climbs His First Peak: The U.S. Army Expedition to the Sources of the Mississippi, 1805–1806 (Lakewood, Colo.: Vrooman-Apfelgold Press, 2006); Matthew L. Harris and Jay H. Buckley, Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012); Jared Orsi, Citizen Explorer: The Life of Zebulon Pike (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pike, “Journal of the Mississippi River Expedition,” in Donald Jackson, ed. The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike: With Letters and Related Documents (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966),1:5–131. In early July, Pike informed Wilkinson that he had completed the task of finishing his reports. Pike to Wilkinson, 2 July 1806, in ibid., 280. |

| ↑3 | It is unclear whether Wilkinson directed Pike to deliberately trespass on Spanish territory in order to be arrested so that Pike could have an opportunity to observe Spanish military strength. Certainly, that would have been critical information for a Wilkinson-Burr plot to invade Spain. William E. Foley, “James Wilkinson: Pike’s Mentor and Jefferson’s Capricious Point Man in the West,” in Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West, 185–225. |

| ↑4 | Wilkinson to Pike, 24 June 1806, in Jackson, Journals of Pike, 1:285–87. The Colorado Springs Pioneer Museum contains many of Donald Jackson’s research notes and papers and is especially rich in Lewis and Clark and Pike material. I am grateful to Matt Mayberry, Leah Davis Witherow, and Kelly Murphy for their assistance in accessing the museum’s collections. Incidentally, the museum hosted Pike’s World: Exploration and Empire in the Greater Southwest, a magnificent Pike Bicentennial exhibit in 2006. |

| ↑5 | Wilkinson to Pike, 12 July 1806, in Jackson, Journals of Pike, 1:288–89. Pike’s journal of the western expedition commences on page 290 and concludes on page 448. Jay H. Buckley, “Pike as a Forgotten and Misunderstood Explorer,” in Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West, 21–59. |

| ↑6 | Pike’s notes and papers were discovered in the Mexican archives by Herbert Eugene Bolton, who published them in the American Historical Review in 1908. Herbert E. Bolton, ed. “Papers of Zebulon M. Pike, 1806–1807,” American Historical Review 13 (July 1908): 798–827. They have since been republished. The Mexican government later relinquished Pike’s papers, and they were delivered to the Archives Division of the Adjutant General’s Office. |

| ↑7 | Current information (unless new evidence surfaces to the contrary) indicates that Pike did not know of Wilkinson and Burr’s plot and remained a loyal American patriot. |

| ↑8 | Nicholas King rendered a hastily prepared version of Pike’s Mississippi route and maps in late 1806 or early 1807. Donald Jackson, ed., The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, with Letters and Related Documents, 2 vols. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 1:131–79. Three years later, the official account was published under the title Zebulon M. Pike, Exploratory Travels through the Western Territories of North America: Comprising a Voyage from St. Louis, on the Mississippi, to the Source of that River, and a Journey through the Interior of Louisiana, and the North Eastern Provinces of New Spain; Performed in the Years 1805, 1806, 1807, by Order of the Government of the United States (Philadelphia: C. and A. Conrad and Co., 1810). For useful editions, see Elliot Coues, ed., The Expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, to Headwaters of the Mississippi River, through Louisiana Territory, and in New Spain, during the Years 1805–6–7, 3 vols. (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1895); Stephen Harding Hart and Archer Butler Hulbert, eds., The Southwestern Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1806–1807, 1932. Reprint, with introduction by Mark L. Gardiner (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006). |

| ↑9 | Clarence E. Carter, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 9, Territory of Orleans, 1803–1811 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940), 909, 927–28, 998–1001; Michèle Butts, “Zebulon Montgomery Pike,” in David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds., Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004), 415–16; and Michael L. Olsen “Zebulon Pike and American Popular Culture; or, Has Pike Peaked?” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 29, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 48–59. Reaching the summit of Pikes Peak inspired Katharine Lee Bates to pen the lines of her most famous poem, “America the Beautiful.” |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.