Learn about the people—and one dog—who were members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Sacagawea

Articles and journal entries

Speaking Hidatsa and Shoshone, she was an interpreter beyond value yet never on the payroll. Still, Sacagawea remains the third most famous member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

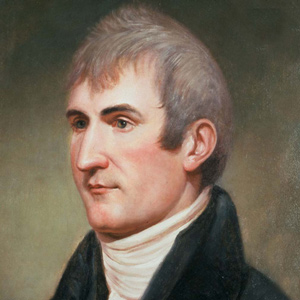

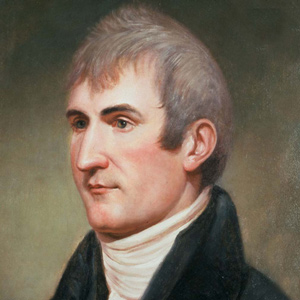

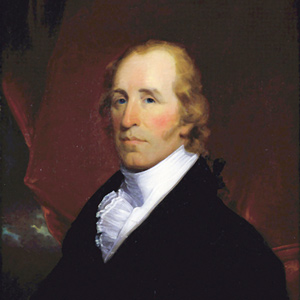

Meriwether Lewis

Explore the complex character and history of Meriwether Lewis before, during, and after the expedition.

The Permanent Party

by Arlen J. Large

Between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean, and on the return to St. Louis, personnel decisions needed to me be made.

William Clark

Clark was a highly intelligent man, and in terms of the practical knowledge required to make his way in the wilderness, to lead men, and to succeed in the world of frontier politics, he was highly educated and consummately effective.

Seaman

Whether he was Lewis’s pet or the expedition’s working dog—or both—he was likely smaller than today’s Newfoundland dog. Did he get lost on the way home or was he present at Lewis’s death?

Two years after the conclusion of the historic Lewis and Clark expedition, York and his enslaver, the Virginia-born patrician William Clark, were at odds.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

by Kristopher K. Townsend

This 9-page series examines the life of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—the infant son of Sacagawea who traveled across the continent with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was educated in St. Louis and Europe, a mountain man, military guide, and California miner.

On 22 December 1803, Drouillard arrived at Clark’s Camp Dubois with the eight lost soldiers from South West Point. They were a disappointing lot, except for Corporal Richard Warfington.

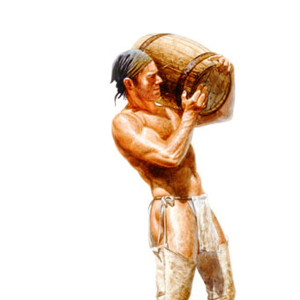

Whether they be boatmen, interpreters, traders, privates in the U.S. Army, diplomats, or cultural guides, the contribution of the French men already living in the Illinois and Louisiana region was “mission critical.”

The Three Squads

Each squad formed a mess responsible for cooking and their own encampment. Privates reported to their sergeant and only sergeants communicated directly with captains Clark and Lewis. When Sergeant Floyd died, private Patrick Gass was elected to replace him.

The Enlisted Men

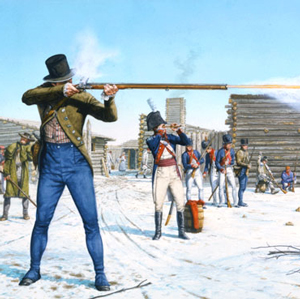

Most of the members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were soldiers in the United States Army. The captains recruited candidates along the Ohio River and military posts on the western frontier. Some would be dismissed early, others would man the barge on its return to St. Louis in 1805, and the rest would become part of the permanent party.

Ohio River Recruits

by Arlen J. Large

Dearborn gave the departing Lewis an order limiting his permanent size to 15 men. These soldiers also were to be obtained at Kaskaskia and other Illinois Army posts, or newly recruited into the Army from “suitable Men” encountered by Lewis along the way.

The Interpreters

Several languages were needed to communicate with the many peoples between St. Louis and the Pacific. At times, long translation chains involving several interpreters were used.

Drouillard was one of the captains’ three most valuable hands. He was also the highest paid member after the captains, he shared the Charbonneaus’ tent with the family and the captains, and he was the only man Clark seemed to call by first name in the journals.

The St. Charles Boatmen

by Jo Ann Brown-Trogdon

The earliest baptism, marriage, and burial registers of St. Charles Borromeo parish help explain the identities and family connections of several of the french boatman from St. Charles.

Moving between Philadelphia and Washington City in 1803, Lewis devised a plan for recruiting personnel while traveling to St. Louis. Plan A was to go down the Cumberland River, Plan B, the Ohio.

While traveling down the Ohio and wintering at Camp River Dubois, the captains searched for army recruits accustomed to the ways of the woods. If they were to survive, the expedition needed hunters.

The Young Men from Kentucky

Clark recruited nine young men from while waiting for Lewis to arrive in Louisville, Kentucky. York could be considered the tenth.

The Enlisted Men

- John Boley -

For John Boley, assigned to the return party, the Corps' 1804 travels apparently whetted an appetite for frontier exploration. After reaching St. Louis on the keelboat in 1805, he volunteered for Zebulon Pike's expedition that was to leave on August 9.

- William Bratton -

On 11 May 1805, Bratton appeared, running toward the river and yelling to be taken aboard quickly. He had shot a grizzly through the lungs, and the wounded bear had chased him for half a mile. The bear had lived at least two hours after first being shot.

- John Collins -

He had gotten off to a bad start, but apparently, the captains, or at least Clark, saw something in him that was worth saving. They would name Idaho's Lolo Creek, Collins Creek.

- John Colter -

Colter left a legacy of western lore, not the least of which was his famous run from the Blackfeet Indians and his exploration of "Colter's Hell." Yet his contributions to the expedition were also many.

- Pierre Cruzatte -

Cruzatte's skills in piloting boats were called on frequently during the expedition. As the main fiddle player, his music brought life to many a celebration. In addition, he could speak Omaha.

- John Dame -

Dame's sole claim to notice in the captains' journals was the fact that he shot an American white pelican at what the captains named Pelican Island, near today's Little Sioux, Iowa.

- Joseph Field -

Joseph yelled to his brother Reubin, who was instantly awake, and the two sprinted for fifty to sixty paces after the natives who were clutching their guns.

- Reubin Field -

Reubin and his brother Joseph (about a year older) were among the best hunters, but Reubin was possibly the better shot. He was, at least, at Camp Dubois on 16 January 1804, when Clark's men set up a shooting match with some local residents.

- Charles Floyd -

Floyd began his journal on 14 May, the day of the expedition's departure from Camp Dubois. On August 18th Floyd wrote his last entry. Shortly after noon on the 20th, Charles Floyd died "with a great deal of composure."

- Robert Frazer -

At a place where "one false Step of a horse would be certain destruction," Frazer's pack horse took that fateful step, lost its footing and rolled with its load "near a hundred yards into the Creek," over "large irregular and broken rocks."

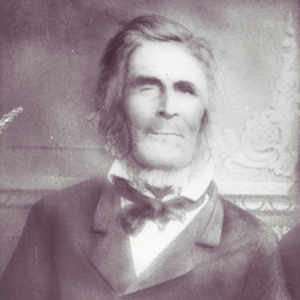

- Patrick Gass -

Starting out as a private with a specialty of carpentry, Gass was soon elected a sergeant after the death of Sergeant Charles Floyd. His was the first expedition journal to be published. He was also the last surviving member.

- George Gibson -

The captains sent four men to retrieve Gibson, "who is so much reduced that he cannot stand alone and...they are obliged to carry him in a litter." They arrived on February 15, and Lewis went to work sweating the "veery languid" Gibson with saltpeter and dosing him with laudanum for sleep.

- Silas Goodrich -

Silas Goodrich was the expedition's principal fisherman. He also did well when trading for food with Indians from time to time.

- Hugh Hall -

As if to confirm the captains' poor evaluation of the new arrivals from Fort Southwest Point, a scant nine days after his arrival, Hall was among a group of six or seven men who got drunk on New Year's Eve.

- Thomas Howard -

On 23 January 1806, Lewis dispatched Howard and Werner to the Salt Camp on the ocean beach, to bring back a supply of salt. When they had not returned by the 26th, Lewis feared they had gotten lost.

- François Labiche -

Labiche performed all the regular duties of an army private, but also performed well as a French and English interpreter. He would continue serving as an escort with Lewis for Chief Sheheke's delegation to Washington City.

- Jean-Baptiste Lepage -

At the age of 43, Lepage was the oldest member of the expedition. He was a French-Canadian trapper and had lived among the Mandan prior to the expedition. His most embarrassing moment may have been losing the pack horse with Lewis's winter clothing.

- Hugh McNeal -

Lewis wrote that "McNeal had exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivulet and thanked his god that he had lived to bestride the mighty & heretofore deemed endless Missouri."

- John Newman -

A Pennsylvanian, he had transferred from Fort Massac into the expedition in the fall of 1803, and was a good member of the expedition until October 1804 when he was convicted of "having uttered repeated expressions of a highly criminal and mutinous nature."

- John Ordway -

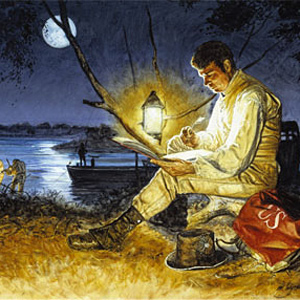

Ordway's journal is the only one carries an entry for every one of the trek's 863 days. Just after the expedition ended, Ordway had purchased the land warrants issued to Jean-Baptiste Lepage and William Werner.

- John Potts -

At Long Camp, Potts nearly drowned when the dugout canoe he was in was swamped in the Clearwater River. But Potts's worst accident happened when the Corps retraced the Northern Nez Perce Trail through the Bitterroots.

- Nathaniel Pryor -

Pryor was assigned several special missions from exploring the Sandy River to escorting Mandan Chiefs to Washington City. He would barely survive his adventures on the Yellowstone River.

- Moses Reed -

Where Reed came from and where he went, no one knows, but as an expedition member, he lasted only until August 1804 when he deserted.

- John Robinson -

This man is perhaps the most mysterious of the expedition's mystery men. Journal entries indicate he may have left the expedition on 12 June 1804 riding back to St. Louis with Chouteau Fur Company traders.

- George Shannon -

Shannon had found the horses, then "Shot away what fiew Bullets he had," failing to get any meat. Eventually, he carved a bullet from a stick and got a rabbit–his only food other than wild grapes during more than two weeks.

- John Shields -

During the damp winter at Fort Clatsop and throughout 1806, the journals speak more and more often about Shields' life-sustaining work as gunsmith. Certainly the guns had seen hard use.

- John Thompson -

On 8 October 1805, the canoe split open and took on water. The Corps encamped for two days to dry out the goods, allowing Thompson to heal a bit.

- Ebenezer Tuttle -

His name appears only one time, when he is listed as a member of Corporal Warfington's detachment bringing the keelboat back from Fort Mandan. He may not have even made it that far.

- Richard Warfington -

On 7 April 1805, Warfington took command of the barge on its return to St. Louis.

- Peter Weiser -

Weiser was a member of Sgt. John Ordway's detachment that paddled the canoes back to the Great Falls. During the 1806 portage around the Falls of the Missouri, he suffered a disabling accident.

- William Werner -

He went with Clark to Ecola Creek on the January 1806 blubber-trading expedition, afterwards being dropped off to take a turn at Salt Camp. He returned to his home state to become a well-established Virginian farmer.

- Isaac White -

The laborer from Boston was to take the boats to the Mandan Villages and then return to Fort Kaskaskia. He may have never gotten that far.

- Joseph Whitehouse -

His journal begins, "about 3 Oclock P.M. Capt. Clark and the party consisting of three Sergeants and 38 men who manned the Batteaux and perogues. we fired our Swivel on the bow hoisted Sail and Set out in high Spirits for the western Expedition."

- Alexander Willard -

Including a court martial, charging grizzlies, and a mile-long swim down the Missouri River, Willard's adventures are well-documented in the journals. He survived them all, crossing the Missouri a final time on his way to California, at age 74.

- Richard Windsor -

Windsor helped recover three orphaned grizzly bear cubs of a sow they killed on a hunt in early April of 1806. According to Lewis, they traded the cubs to some coastal Indians, who, "fancyed these petts and gave us wappetoe in exchange for them."

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.