“Legacy is a very slippery sort of term. How do you define the legacy of any historical event? How do you measure it? If we could erase our myth concepts of Lewis and Clark . . . it might reawaken something really extraordinary in our national consciousness”

The Charbonneaus in St. Louis

by Robert J. Moore

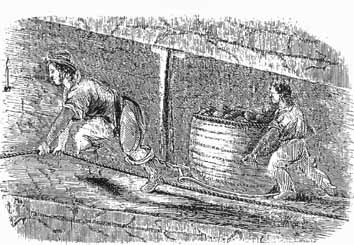

In 1809, Toussaint, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste Charbonneau traveled to St. Louis. Jean Baptiste’s baptism began a new era in his life, is father would try to become a farmer, and Sacagawea would become sickly.

On 7 April 1805 three ‘heroic’ events occurred. The expedition set off from Fort Mandan, and Beethoven premiered his Third Symphony, the “Eroica,” dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte. It was also the day Great Britain and Russia sealed a fateful alliance against that French emperor.

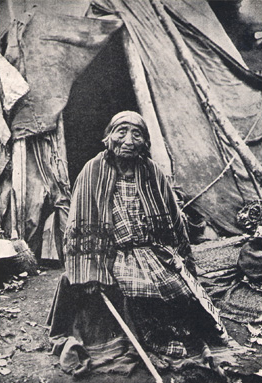

The Montana Frontier

Lewis and Clark returned with reports of sweeping grasslands, abundant beaver, large seams of coal, endless buffalo herds. In the years that followed, Euro-Americans settlement increased and Native American populations decreased in an era known as the Montana frontier.

Did they take on too much risk when they split into small groups on the way home? Did the Lewis and Clark Expedition actually fail?

Sheheke’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Sheheke’s diplomatic trip to Washington City and his difficult return home brought down the careers of at least two great leaders—himself, and Meriwether Lewis.

On 23 March 1806, once again battling the rising spring runoff, as it had each of the two previous years on the Missouri, the Corps of Discovery started up the Columbia River towards home.

Lewis was about to journey to Washington to face his accusers. He only made it as far as Grinder’s Stand. But did he commit suicide or was he murdered?

Publications that attempted to tell the story of Lewis and Clark were being printed before Lewis and Clark had even returned from their trans-Mississippi exploration. Their popularity continued for approximately ten years after they returned to St. Louis.

The Lewis and Clark’s bear claw necklace, recently ‘rediscovered’, is described and analyzed and suggests some of the many meanings and provocations related to it.

For nearly 100 years, the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s full contribution to natural science was underpublished and a disappointment to many scientists expecting to learn more about the natural history of the regions explored. When it came to the mosquito, these naturalists were doubly disappointed.

To the European Romantics, the gritty names those American explorers uttered sounded like throwbacks to a cruder, more barbarous epoch, boding ill for the future of poetic taste in the New World. In 1815, Robert Southey found plenty of evidence.

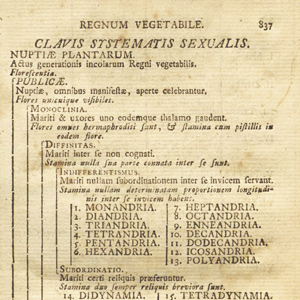

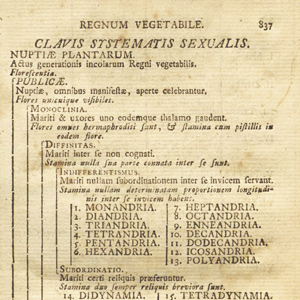

The science of the orderly classification of all living and extinct organisms is called taxonomy. It comprised a hierarchical outline of descriptors extending between the most general and the most specific and Lewis and Clark had a role.

Two days after returning to St. Louis, its citizens celebrated the expedition’s return with a grand dinner and ball. Here are the eighteen toasts as reported in the Kentucky Western World.

Assessing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The author proposes a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

Bostonian George Ticknor catalogued the “strange furniture” of the four walls of the room after his visit in 1815, listing heads and horns, “curiosities which Lewis and Clark found on their wild and perilous expedition,” mastodon bones, and the two Native American painted hides.

Lewis and Clark reported seeing layers of coal along the Missouri River’s northern reach. Jefferson had only to look to Great Britain, already fifty years into the Industrial Revolution, to see what was coming.

Post-expedition Botany

Lewis worked under trying and difficult situations. While it is clear that he was only able to devote a portion of his time to the effort, what he did is widely respected.

Influence on Science

The captains’ careful observations of the geography, natural history, and ethnography of the American west and Pacific Northwest influenced many scientists who built on their work.

The story Wheeler wished to tell can be found in his book’s subtitle: “A story of the great exploration across the Continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later.”

A reason for their continuing popularity may be traced to nineteenth century literature and the stimulation of interest in reading and teaching that brought fictionalized versions of the Lewis and Clark story to generations of young readers.

The stuffed birds and mammals, the skins and skeletons, and especially the Indian artifacts, that Peale received—mainly from Lewis, through Jefferson—greatly benefited the museum and consequently the public’s appreciation of the expedition.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.