Was York ever given his freedom?

Doubts about Clark’s Account

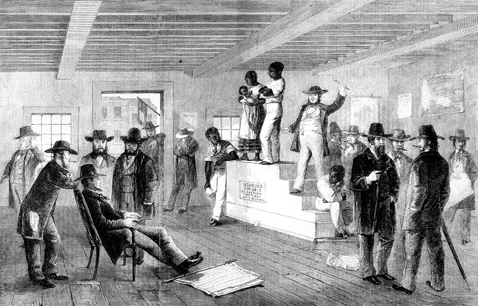

Slave Pen at New Orleans, Before the Auction

Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

Wood Engraving, Harper’s Weekly, January 24, 1861

The caption for this drawing reads:

“In connection with the gradual downfall of slavery, we publish on this page an illustration of a gang of negroes in a slave-pen at New Orleans before an auction. The picture is from a sketch taken by a foreign artist before the war. In describing it the artist wrote:”

‘The men and women are well clothed, in their Sunday best—the men in blue cloth of good quality, with beaver hats; and the women in calico dresses, of more or less brilliancy, with silk bandana handkerchiefs bound round their heads. Placed in a row in a quiet thoroughfare, where, without interrupting the traffic, they may command a good chance of transient custom, they stand through a great part of the day, subject to the inspection of the purchasing or non-purchasing passing crowd. They look heavy [grave], perhaps a little sad, but not altogether unhappy.’

There are a number of reasons to doubt Clark’s account of York’s end. First, as Robert Betts notes in the most extensive examination of York to date, “Actually, the only source that York was freed is Washington Irving in the notes he made of his conversation with Clark in 1832.” It was “at some unspecified point in time York had been granted his freedom.”

Second, it is remarkable that we have no record of York’s words and thoughts. Insofar as the nineteenth century “slave narratives” were produced by Africans who had freed themselves, it may be conjectured that York did not leave a record of his thoughts and experiences because he was never freed. Certainly, he would not have been unaware of the significance of his story, nor undesirous of telling it.

Third, Clark’s twenty-four-year hostility toward York is striking. According to Irving’s notes, York failed in his business because he disliked getting up early in the morning, was easily cheated, did not keep his horses well, and grew to hate the responsibilities associated with being free. But this could well be a description of York’s escalating protest as driver/operator in Clark’s and his nephew’s business because of Clark’s refusal to free him.

In other words, Clark’s bitterness toward York could well be explained by the possibility that York sabotaged Clark’s business. There is little doubt that Clark’s pride would have prevented him from admitting to Irving the humiliation of having been bested by a slave.

Further, according to the notes, all the Africans Clark allegedly freed eventually grew to prefer enslavement by him to personal freedom and independence, a statement that, if nothing else, sounds patently self-serving.

Betts’s analysis of this is quite revealing. “Irving’s words . . . leave little question that Clark spoke sardonically of York.” Clark painted an “unflattering portrait of the man who had long been his body servant and had accompanied him on the historic crossing of the continent.” Betts further adds: “Those who held black men and women in bondage, as Clark still did, had to believe that slaves were happier and better off under the firm guidance of a master than in trying to wrestle with the problems freedom brought.”

Did York Escape?

In all, the vagueness of circumstances surrounding York’s being freed and his death, the implausible account of York’s supposed failure with and hatred of freedom, and Clark’s continuing bitterness, simply casts doubts upon Clark’s credibility.

Added together, these factors also lend strength to another possibility that York may have escaped to freedom. After all, Clark admits York never returned to him. Betts cites evidence of a witness who in 1832 (the same year Clark told Irving York had died in Tennessee) and in 1834 saw and met with an elderly African man living among the Crows in north-central Wyoming. The man, who appears to have fit York’s description in size, complexion and age, boasted of having participated in the Lewis and Clark Expedition and of having happily escaped from enslavement in the United States.[1]Robert B. Betts, In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark (Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985), 135-43.

Whose Hero? Whose Victim?

For Americans York today assumes the role of hero in a revised reflection upon their history. Now is a time when Americans are reassessing their trespasses against others and attempting to make amends by posthumously recognizing the contributions to their nation of those they despised and persecuted during their lifetimes. Hence, whether York was or is a hero to Americans is something for them to decide.

Whether he was or is a hero to Americans, however, is hardly relevant to Africans. If there is anything heroic about York, to Africans it is certainly not the fact he participated in an event in American history that, in the end, did little for them except strengthen the regime that oppressed and persecuted them. Rather, what is heroic about York’s life is his conversion to uncompromised resistance to oppression, his personal refusal and inability to surrender despite all costs, and the possibility that he may have succeeded both in destroying his enslaver’s business and escaping to freedom in a final, triumphant act of self-liberation.

For Africans the overriding reality remains that York was a victim, a man whose talents, aspirations, and life possibilities were aborted and exploited to satisfy the needs and interests of those who held his humanity in contempt. One can only hope that York in the end escaped, that he was able to wrest for himself some sphere of dignity and independence in his final years to give meaning to his life and to justify the human struggle to be free.

Additional Sources:

Ambrose, Stephen E., Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., 1996.

Berry, Mary Frances, and John Blassingame. Long Memory: The Black Experience in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Franklin, John Hope and Albert A. Moss, Jr. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African-Americans. Seventh edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Gates, Henry Louis, ed., The Classic Slave Narratives. New York: Mentor, 1987.

Harding, Vincent. There is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America. New York: Vintage Books, 1981.

Taylor, Quintard, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African-Americans in the American West, 1528-1990. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to York’s Fallout over Freedom:

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert B. Betts, In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark (Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985), 135-43. |

|---|