As describers of the natural world they encountered on the expedition, Lewis and Clark influenced—and were influenced by—several people who could now be called naturalists. Explore here the unique connections these naturalists shared with the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Naturalists

Everywhere Nuttall went he found new and curious plants. Unlike most who came before him, he collected even the unattractive plants. From him, long-leaved sage and white sage, first collected by Lewis, became known to science.

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Lesueur spent 10 years in Philadelphia, where he was an associate of Academy of Natural Science founder William Maclure. He gathered and drew many zoological specimens a few of which are used on this site.

In Cuvier’s time, the idea of extinction was entertained, but it was still in dispute. What was most difficult to ascertain was what extinction meant in understanding the history of the earth.

Georges Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, was the most influential biologist of the 18th century. The title of Count was bestowed not by birth, but by Louis XV in recognition of his accomplishments.

In 1792, André Michaux approached members of the American Philosophical Society informing his potential sponsors that he was “ready to go to the sources of the Missouri and even explore the rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean.”

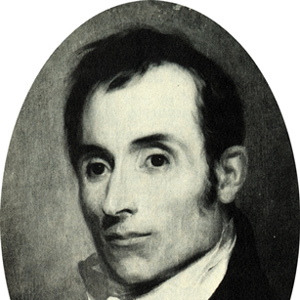

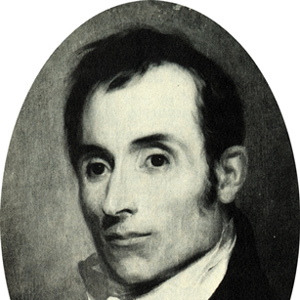

Caspar Wistar

Philadelphia mentor

When Lewis met him, Wistar was an eminent physician and professor—popular with his students, beloved by his patients. In 1811, he completed and published the first volume of A System of Anatomy for the Use of Students of Medicine.

Perhaps the naturalist most influenced by Lewis and Clark was Alexander Wilson. Considered by many as the “Father of American Ornithology” he actively used their writings and specimens to complete his own works.

Rafinesque took a scientific interest in the plants and animals mentioned by Lewis and Clark. In addition to the six species of conifers, he also established the scientific name for the prairie dog, the white-footed mouse and the mule deer.

Even in Lewis and Clark’s day, new species were being classified using a system developed by naturalist Carl Linnaeus.

No other botanical explorer in western North America is more famous than David Douglas. His name is associated with hundreds of western plants, and may also be found on mountains, rivers, counties, schools and even modern-day streets.

During the winter of 1807-1808, Pursh lived at the home of Bernard McMahon in Philadelphia. Here he worked on the drawings and descriptions of Lewis’s western plants.

Important for the history of the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, its first plant specimens were consigned to Barton’s care. Here began the disassembling of the collection, and his promised volume on natural history was never written.

The son of a farmer and merchant in Philadelphia, Richard Harlan became a leading American figure in anatomical studies. He would become the man who named the only fossil that now survives from the Lewis and Clark expedition.

America’s greatest ornithologist, John James Audubon, was just starting his career when Lewis and Clark returned, and there is ample evidence that he drew inspiration from Lewis and Clark’s writings.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.