Floyd’s grave became a conspicuous point for historic memorials on the Lewis and Clark trail almost immediately after the expedition was over. To begin with, the steadily increasing movement of trappers and traders up the Missoula would have quickly spread the word that only one member of the party had died, and that his grave was on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River about 950 miles from its mouth. Many of the early travelers were in small parties bound for the new territory’s beaver fields, and the “jawbone journals,” as the late historian Jim Large called the spontaneous, one-on-one oral medium, worked faster and spread the word more widely than one might think.

Floyd’s Bluff

George Catlin, 1832

Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Luce Foundation Center, 1985.66.376.

The American artist George Catlin (1796-1872) painted Floyd’s Bluff in 1832, with the original cedar marker still in place. The following year Prince Maximilian von Wied, the Prussian explorer and man of science, noticed that someone had erected a new cedar post after prairie fire damaged it.

In May 1807, only 8 months after the expedition disembarked at St. Louis, the Pittsburgh bookseller David McKeehan published Sergeant Patrick Gass‘s journal, titled A Journal of the Voyages & Travels of a Corps of Discovery, under the Command of Captain Lewis and Captain Clarke of the Army of the United States. The prospectus appeared in the Pittsburgh Gazette in March, and the first review of it appeared on 1 June 1809 in The Monthly Anthology, and Boston Review. The Anthology‘s critic granted that Gass’s book was “written without lofty pretensions,” and that “as it is without a map, it cannot be of very lasting importance; yet it furnishes some details to satisfy us for the moment, till we are favoured with the principal work” that Meriwether Lewis had promised in early April 1807 but was never to be published.

In 1848 a man named William Thompson built a cabin on the bluff near Floyd’s grave, and the following year a French Canadian trader for the American Fur Company settled at the mouth of the Big Sioux River. In 1854 a surveyor for the U.S. government laid out a town between the Big Sioux and Floyd’s River, a logical place for a settlement, inasmuch as it had long been a favored fording place, campsite and gathering point of the Yankton Sioux and other Indian tribes. In only four more years the new town gained official identity with a post office, and saw the first steamboat arrive from St. Louis.

Floodwaters undermined the bluff early in the spring of 1857, and part of the grave slid toward the river. Local citizens who were aware of the significance of the site quickly recovered all but a few bones, and on 28 May 1857, Floyd’s remains were buried for the third time, with appropriate military and religious ceremonies, 200 yards east of their original burial. New wooden markers were erected, but over the next four decades they were steadily whittled away by souvenir hunters, and grazing cattle obliterated all other evidence of the gravesite.

Sergeant Floyd’s grave as relocated in 1857

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

This second gravesite was between the two large posts.

Stone slab placed on Floyd’s Bluff 30 August 1895

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804—1904, Vol. 1, p. 90.

Five years later the sergeant’s remains were disinterred for reburial a third time beneath the 100-foot-tall obelisk. The fate of the stone slab thereafter is unknown.

The inscription on the stone read:

Sergeant

CHARLES FLOYD

DIED

Aug. 20. 1804.

Remains removed from 600

Feet West and Reburied at

This Place May 28. 1857.

This Stone Placed

Aug. 20. 1895.

“Floyd’s Bluffs, Iowa. May 3rd 1866”

Looking up the River from the Steamboat Walter B. Dance

Courtesy Montana Historical Society, X1968.43.01b.

Graphite on paper, 1866, by Granville Stuart (1863-1918).

The X marks the location to which the grave was moved in 1857.

In 1893 Floyd’s long-lost journal came to light, and the publication of it served to revive public interest in the site.[1]Reuben Gold Thwaites rediscovered Floyd’s journal at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin in 1893. It was first published in 1894 in the American Antiquarian Society Proceedings by James … Continue reading On 20 August 1895, the sergeant’s remains were interred for the third time, beneath a three-by-seven-foot marble slab, and plans were begun to erect a more fitting monument to his memory.

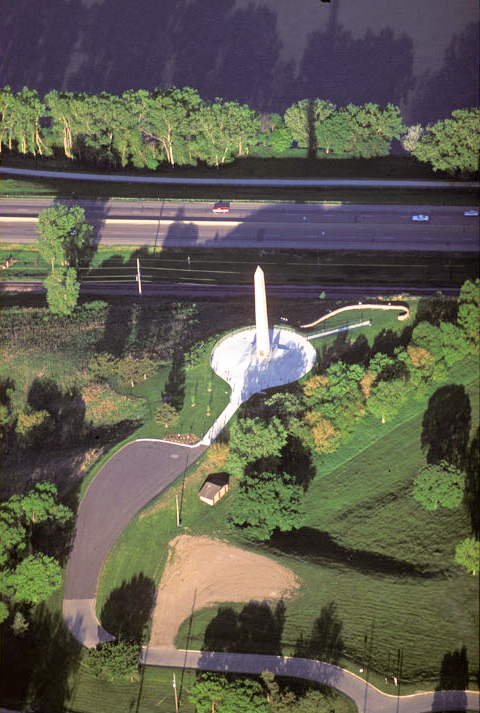

On 20 August 1900, Floyd’s bones were reburied for the fourth and last time. On 30 May of the following year the present hundred-foot-high sandstone obelisk was dedicated, and Floyd’s place in American history was commemorated with due ceremony. In October of 1966 the monument became the first site to be listed in the newly established National Registry of Historic Places.

See also Floyd’s Monument by Air.

Floyd’s Monument Today

Jim Wark, photo.

On 27 October 1997, the plaza surrounding the monument was dedicated to the memory of Dr. V. Strode Hinds(1927-1997), of Sioux City, Iowa, “a man who brought Lewis and Clark history to life through his programs, conversations and work with people of all ages.” Dr. Hinds was a president of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation in 1981-82.[2]V. Strode Hinds, “Reconstructing Charles Floyd,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27, No. 1 (February 2001), 16-19. See also James J. Holmberg, “Monument to a y’oung Man of Much … Continue reading

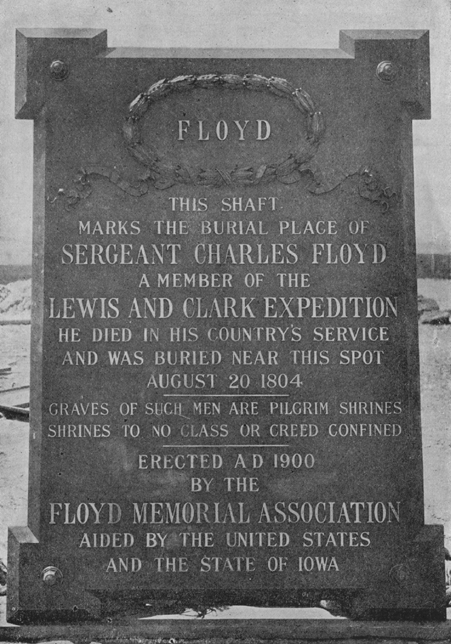

Transcription:

Floyd

This shaft marks the burial place of Sergeant Charles Floyd a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

He died in his country’s service and was buried near this spot August 20 1804

Graves of such men are pilgrim shrines

Shrines to no class of creek confined

Erected A D 1900 by the Floyd Memorial Association aided by the United States and the State of Iowa

The Sergeant Floyd Monument is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site is managed by the Sioux City Museum.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Reuben Gold Thwaites rediscovered Floyd’s journal at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin in 1893. It was first published in 1894 in the American Antiquarian Society Proceedings by James D. Butler. Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 128. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | V. Strode Hinds, “Reconstructing Charles Floyd,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27, No. 1 (February 2001), 16-19. See also James J. Holmberg, “Monument to a y’oung Man of Much Merit’,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 22, No. 3 (August 1996), 4-13. Holmberg, “The Life, Death, and Monument of Charles Floyd.” http://www.lewisandclarkinkentucky.org/people/floyd_article.shtml (accessed 06/08/2013). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.