Hidatsa Territory About 1800

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark arrived, the Hidatsa were using a vast area vaguely defined by the Mouse (Souris) River on the north, the Turtle River on the east near today’s border with Minnesota, the Heart River on the south, and the Yellowstone River on the west. ‘Legal’ boundaries were unheard of.

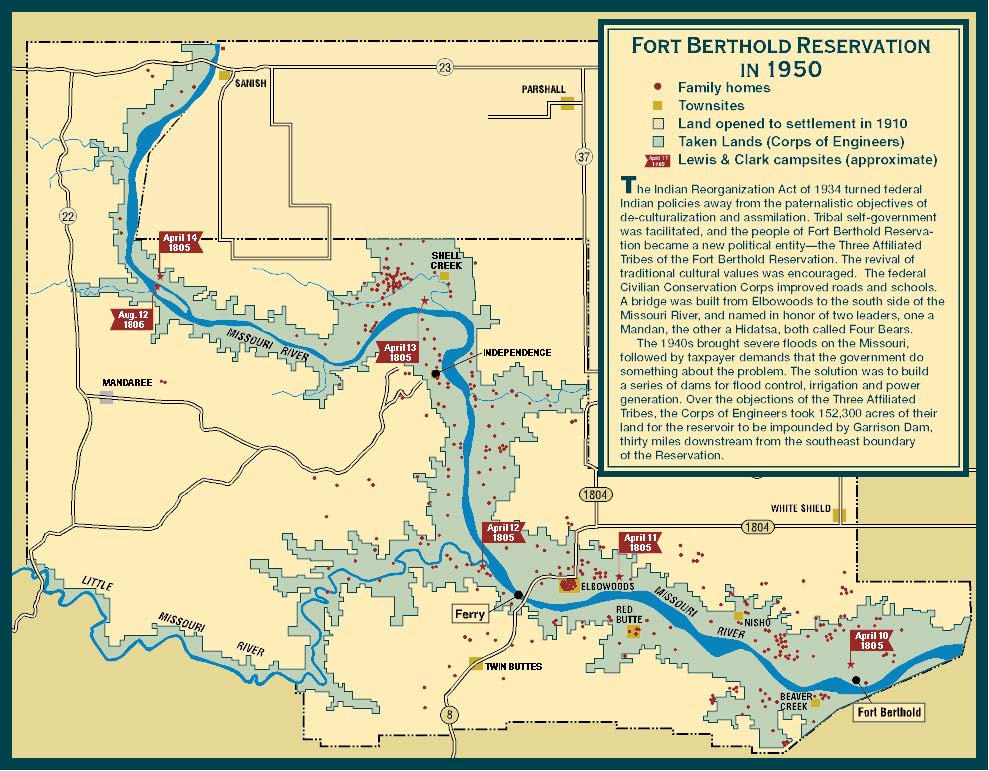

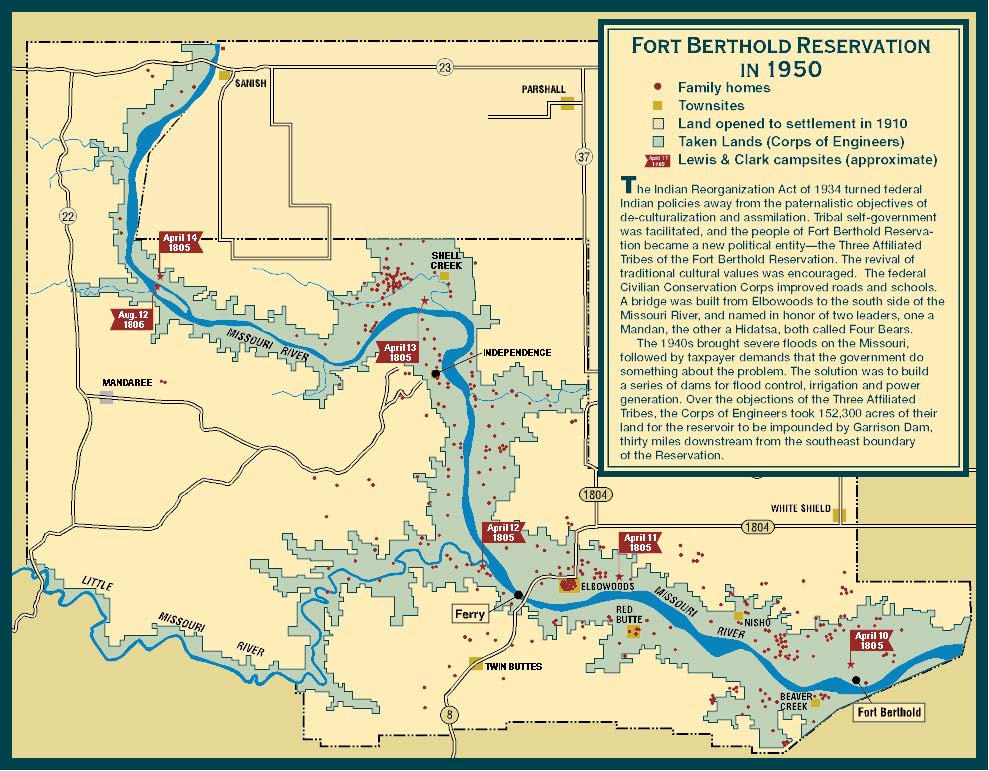

Fort Berthold Reservation in 1950

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 turned federal Indian policies away from the paternalistic objectives of de-culturalization and assimilation. Tribal self-government was facilitated, and the people of Fort Berthold Reservation became a new political entity—the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. The revival of traditional cultural values was encouraged. The federal Civilian Conservation Corps improved roads and schools. A bridge was built from Elbowoods to the south side of the Missouri River, and named in honor of two leaders, one Mandan, the other a Hidatsa, both called Four Bears.

The 1940’s brought severe floods on the Missouri, followed by taxpayer demands that the government do something about the problem. The solution was to build a series of dams for flood control, irrigation and power generation. Over the objections of the Three Affiliated Tribes, the Corps of Engineers took 152,300 acres of their land for the reservoir to be impounded by Garrison Dam, thirty miles downstream from the southeast boundary of the Reservation.

To learn more about the sites illustrated on the map above, click any of the links below:

Journal, 14 April 1805

In my walk of this day, which was through the wooded bottoms and on the hills for several miles back from the river . . . I Saw the remains of two Indian incampments with wide beeten tracks leading to them. Those were no doubt the Camps of the Ossinnaboin Indians (a Strong evidence is hoops of Small Kegs were found in the incampments). No other nation on the river above the Sioux make use of Spiritious licquer. . . .

The River Continues wide and the current jentle not more rapid than the Current of the Ohio in middle state. The bottoms are wide and low and the moist parts of them Contain Som wood such as cotton, Elm & Small ash, willow, rose bushes &c. &c. & . . . . The hills are high broken in every direction, and the mineral appearance of Salts Continue to appear in a greater perportion, also Sulpher, Coal & bitumous water in a Smaller quantity.

I saw Buffalow on the L. S. Crossed and dureing the time dinner killed a Bull, which was pore, we made use of the best of it.

Capt. Lewis walked out . . . and killed an Elk which he found So meager that it was not fit for use, and joined the boat at Dusk on the S. S. opposit a high hill Several parts of which had Sliped down. On the side of those hills we Saw two white bear [grizzlies] running from the report of Capt. Lewis Shot. Those animals assended those Steep hills with Supprising ease & verlocity.

William Clark

Journal, August 12, 1806

At meridian Capt. Lewis hove in Sight with the party which went by way of the Missouri as well as that which accompanied him from Travellers rest on Clarks river. I was alarmed on the landing of the Canoes to be informed that Capt. Lewis was wounded by an accident.

I found him lying in the Perogue. He informed me that his wound was slight and would be well in 20 or 30 days. This information relieved me very much. I examined thw ound and found it a very bad flesh wound. The ball had passed through the fleshey part of his left thy below the hip bone and cut the cheek of the right buttock for 3 inches in length and the debth of the ball.

Capt. L. informed me the accident happened the day before by one of the men, Peter Crusat, misstakeing him in the thick bushes to be an Elk. Capt. Lewis with this Crusat and Several other men were out in the bottom Shooting of Elk, and had Scattered in a thick part of the woods in pursute of the Elk. Crusat Seeing Capt. L. passing through the bushes and takeing him to be an Elk from the Colour of his Cloathes which were of leather and very nearly that of the Elk, fired, and unfortunately the ball passed through the thy as aforesaid.

Capt. Lewis, thinking it indians who had Shot him hobbled to the canoes as fast as possible and was followered by Crusat. The mistake was then discovered. This Crusat is near Sighted and has the use of but one eye.1 He is an attentive, industerous man, and one whome we both have placed the greatest Confidence in dureing the whole rout.

William Clark

1. One suspects that there was a misunderstanding on Clark’s part here. If Pierre Cruzatte was truly nearsighted, how could any confidence have been place in him as a riverman? That job would have required him to read the intricate, continuously-changing surface of the river at a distance.

Journal, April 13, 1805

The wind was in our favour after 9 A. M. and continued favourable untill 3P.M. We therefore hoisted both the sails in the White Perogue, consisting of a small squar sail, and spritsail, which carried her at a pretty good gate, untill about 2 in the afternoon when a suddon squall of wind struck us and turned the perogue so much on the side as to allarm Sharbono who was sterring at the time.

In this state of alarm he threw the perogue with her side to the wind, when the sprit-sail gibing was as near overseting the perogue as it was possible to have missed. The wind however abating for an instant I ordered Drewyer to the helm and the sail to be taken in, which was instant executed and the perogue being steered before the wind was agin plased in a state of security.

This accedent was very near costing us dearly. Beleiving this vessel to be the most steady and safe, we had embarked on board of it our instruments, Papers, medicine and the most valuable part of the merchandize which we had still in reserve as presents for the Indians. We had also embarked on board ourselves, with three men who could not swim and the squaw with the young child, all of thom, had the perogue overset, would most probably have perished, as the waves were high, and the perogue upwards of 200 yards from the nearest shore.

However we fortunately escaped and pursued our journey under the square sail, which shortly after the accident I directed to be again hoisted.

Meriwether Lewis

Journal, April 12, 1805

Set out at an early hour. Our peroge and the Canoes passed over to the Lard side in order to avoid a bank which was rappidly falling in on the Stard. The red perogue contrary to my expectation or wish passed under this bank by means of her toe line, where I expected to have seen her carried under every instant. I did not discover that she was about to make this attempt untill it was too late for the men to reembark, and retreating is more dangerous than proceeding in such cases. They therefore continued their passage up this bank, and much to my satisfaction arrived safe above it. This cost me some moments of uneasiness. Her cargo was of much importance to us in our present advanced situation.

We proceeded on six miles and came too on the lower side of the entrance of the little Missouri on the Lard shore in a fine plain where we determined to spend the day for the purpose of celestial observation. . . .

Remarks

The artifil. Horizon recommended by Mr. A. Ellicott, in which water forms the reflecting surface, is used in all observations which requirs the uce of an Artificial horizon, except when expressly mentioned to the contrary.

Meriwether Lewis

Journal, April 11, 1805

Set out verry early. I walked on Shore, Saw fresh bear tracks. One deer & 2 beaver killed this morning. In the after part of the day kiled two gees. . . . The plains begin to have a green appearance. The hills on either side are from 5 to 7 miles asunder and in maney places have been burnt, appearing at a distance of a redish brown choler, containing Pumic Stone & lava, Some of which rolin down to the base of those hills— In maney of those hills forming bluffs to the river we procieve Several Stratums of bituminious Substance which resembles Coal, thoug Some of the pieces appear to be excellent Coal. It resists the fire for Some time, and consumes without emiting much flaim.

The plains are high and rich. Some of them are Sandy Containing Small pebble, and on Some of the hill Sides large Stones are to be Seen— In the evening late we observed a party of Me ne tar ras on the L. S. with horses and dogs loaded going down. Those are a part of the Mennetarras who camped a little above this with the Ossinniboins at the mouth of the little Missouri all the latter part of the winter.

William Clark

Journal, April 10, 1805

The Corps of Discovery left its winter camp near the Mandan villages on 7 April 1805. By the 10th, according to their estimate, they had covered 45.5 miles, though it’s actually about 65 miles from the presumed site of Fort Mandan to the vicinity of their encampment of this date.

Set out at an early hour this morning. At the distance of three miles passed some Minetares1 who had assembled themselves on the Lard shore to take a view of our little fleet. . . .

The country on both sides of the missouri from the tops of the river hills, is one continued lefel fertile plain as far as the eye can reach, in wich there not even a solitary tree or shrub to be seen except such as from their moist situations or the steep declivities of hills are sheltered from the ravages of the fire. . . .

At 1 P. M. we overtook three french hunters who had set out a few days before us with a view of traping beaver. They had taken 12 since they left Fort Mandan. These people avail themselves of the protection which our numbers will enable us to give them against the Assinniboins who sometimes hunt on the Missouri and intend ascending with us as far as the mouth of the Yellow stone river and continue there hunt up that river. This is the first essay of a beaver hunter of any discription on this river.

Meriwether Lewis

1. Hidatsa Indians. Minetare, or Minitare, meaning “water ford,” was the Mandan Indians’ name for the Hidatsa people. Some unidentifiable person, at some unknown point in time, for some unexplainable reason, evidently made a sign-language gesture indicating “hungry” in reference to this tribe. A French trader, interpreting the gesture to mean gros ventre, or “big belly.” Lewis and Clark understood Minitare and Big Belly to refer to the same people.

Today, Indian ethnology makes a clear distinction between the two. The Gros Ventre are an Algonkian-speaking people who live with the Assiniboines on the Fort Belknap Reservation in northeastern Montana. The Hidatsas, sometimes referred to as the Gros Ventre of the Missouri, belong to the Siouan linguistic family.

See Eagle/Walking Turtle, Indian America: A Traveler’s Companion (Fourth edition, Santa Fe: John Muir Pulibcations, 1995), 34-37.

Vicinity of Fort Berthold and Like-A-Fishook Village

Documentary Photo, ca. 1953

North Dakota Heritage Center

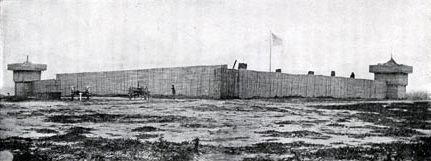

Fort Berthold

Fort Berthold was not a military fort but a fur trading post first called Fort James, which was established here in 1845 by James Kipp. It was acquired in 1846 by the firm of Pierre Chouteau, Jr., and Company and renamed for one of the partners in the fur company. Several years later another post with the same name was built in that vicinity.

Also in 1845 the Mandans and Hidatsas, needing to move from their settlements around the mouth of the Knife River, where the wood supply had become depleted, established a new village some fifty miles upriver near Fort Berthold, naming it “Like-A-Fishook.”

Born in Italy in 1781, Berthelemi Antoine Mathias Bertolla de Mocenigo (whose brother, in Venice, manufactured glass beads for the fur trade) emigrated to America in 1798 and changed his name to Bartholomew Berthold. He moved to Saint Louis in 1809 and soon became one of the city’s most distinguished and successful merchants. In partnership with his wife’s brother, Pierre Chouteau, Jr., and two of her cousins, he purchased the Western Department of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company in 1834.

Sources:

Roy Willard Meyer, The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri: The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977), pp. 100-101.

Charles van Ravenswaay, Saint Louis: An Informal History of the City and its People, 1764-1865 (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1991), 99-100.

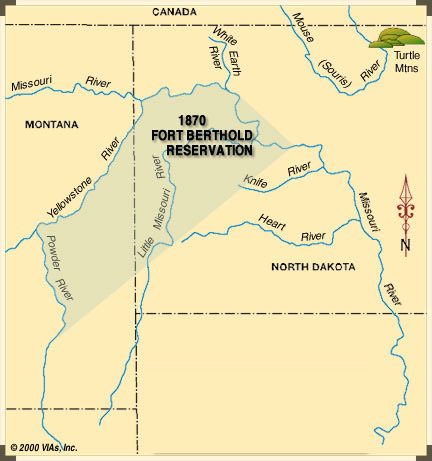

Changing Reservation Borders

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1851 Treaty

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 specified the legal boundaries of the land of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people. It contained an estimated 12.6 million acres.

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1870

Fort Berthold Reservation was established in 1870. Though neither Congress nor the Indian people ever agreed to the change, the old reservation shrank to about 7.8 million acres, owned communally by the tribe. The land of the Knife River Villages, where Lewis and Clark had wintered among the Mandan, was no longer theirs.

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1880

In 1880 the Northern Pacific Railroad needed land for its right-of-way through the reservation, plus some more to sell to white settlers. The U.S. Government, without consulting Congress or the Indians, exchanged much of the southern half of the reservation for a little land north of the Missouri River, leaving the tribes 1.2 million acres.

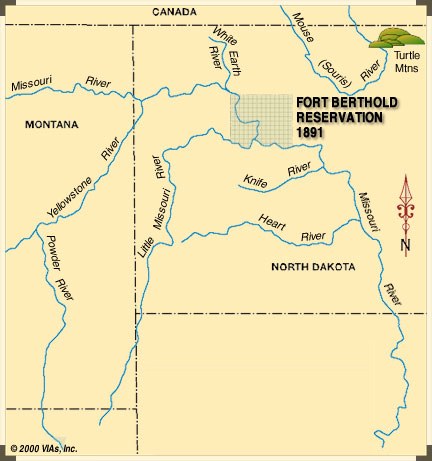

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1891

The General Allotment Act of 1887 introduced private land ownership—basically 160 acres per family, plus a few extra acres for a wife and children. In 1891 Congress declared two-thirds of the reservation to be ‘surplus’ land, and sold it. The three tribes received $800,000, which was used for support of the Indian agency, schools, and the mission.

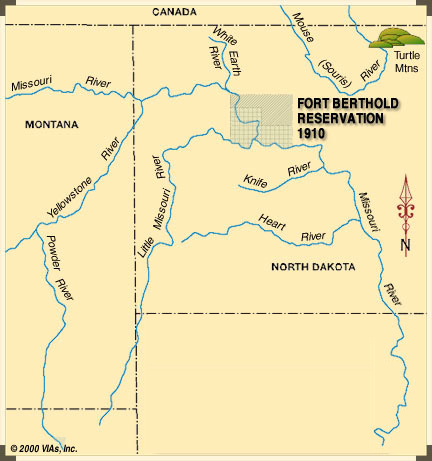

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1910

In 1910 the Government sold the northeast corner of Fort Berthold Reservation to white settlers, although the courts later confirmed it was still part of the 930,000-acre reservation. In 1954 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, pursuant to the Pick-Sloan Plan, took 192,300 acres for the reservoir, Lake Sakakawea, behind Garrison Dam, leaving the Three Tribes with 777,700 acres.

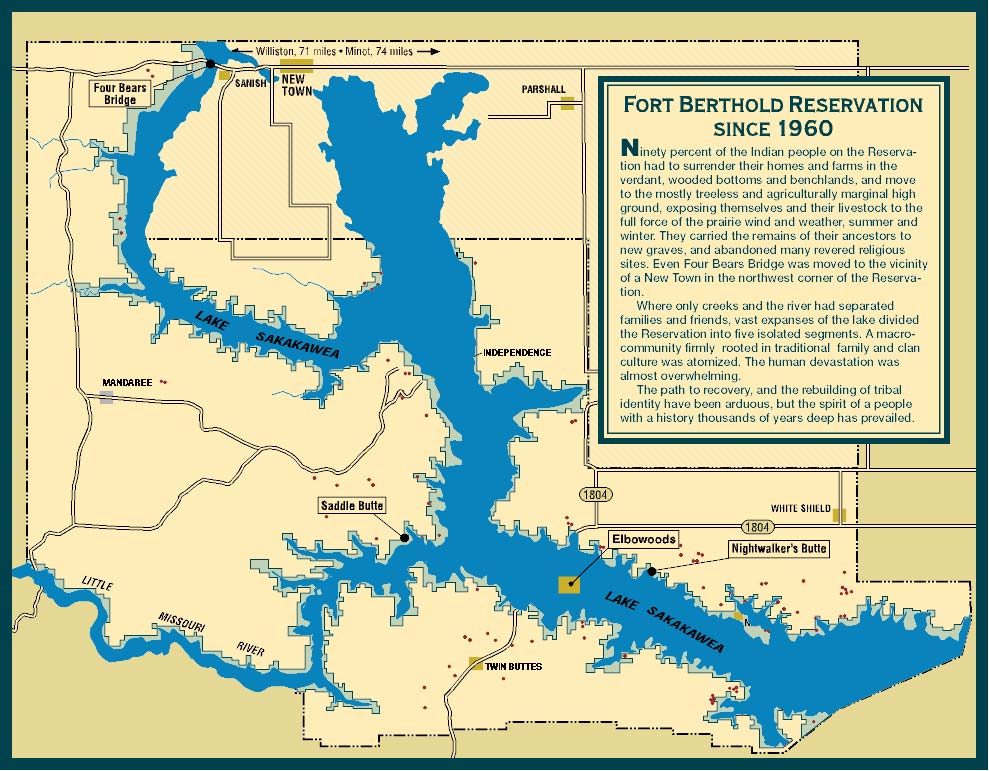

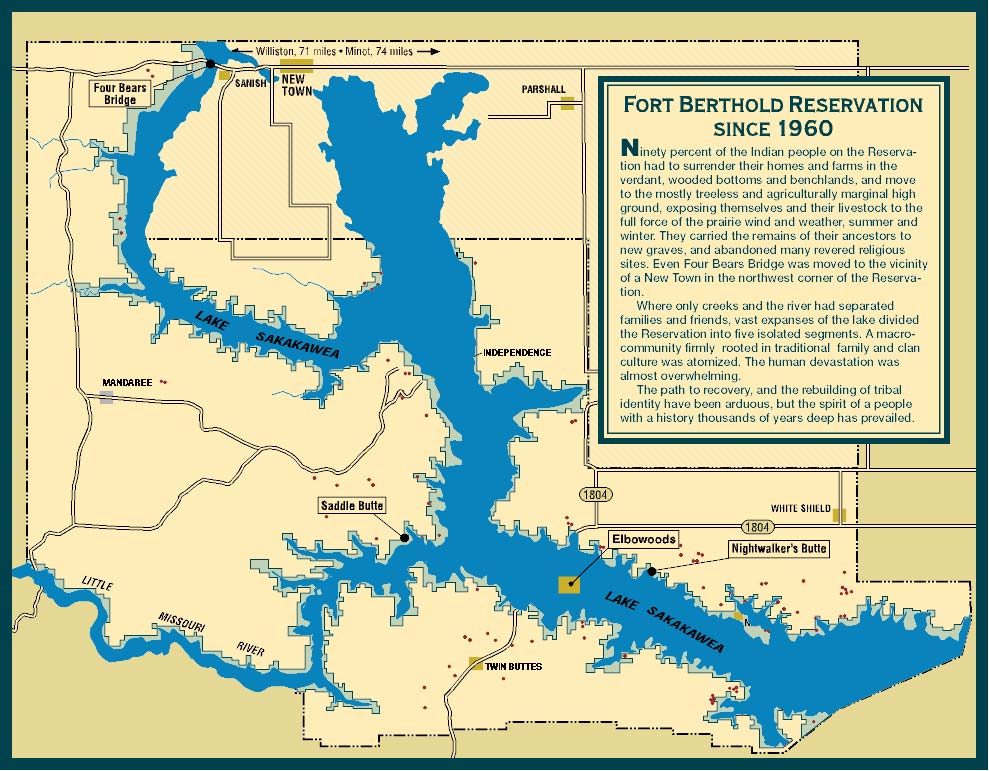

Today’s Reservation

Ninety percent of the Indian people on the Reservation had to surrender their homes and farms in the verdant, wooded bottoms and bench lands, and move the mostly treeless and agriculturally marginal high ground, exposing themselves and their livestock to the full force of the prairie wind and weather, summer and winter. They carried the remains of their ancestors to new graves, and abandoned many revered religious sites. Even Four Bears bridge was moved to the vicinity of a ‘New Town’ in the northwest corner of the Reservation.

Where only creeks and the river had separated families and friends, vast expanses of the lake divided the Reservation into five isolated segments. A macro-community firmly rooted in traditional family and clan culture was atomized. The human devastation was almost overwhelming.

The path to recovery, and the rebuilding of tribal identity have been arduous, but the spirit of a people with a history thousands of years deep has prevailed.

Commentary

Starting from the Cannonball River, the boundary line runs southwest to the Black Hills along the divide into the Powder River westward, following Powder River it runs north, crossing the Yellowstone River. Going straight north into the Missouri River, crossing the Missouri into Muddy Creek. Following Muddy Creek it runs to the Canadian Border Line. From the Border Line it runs along the Line eastward up to the corner straight north of Devil’s Lake, North Dakota, from that corner, going south back to the Cannonball River. This is the exact mark of the boundary line which was established in the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1851.

Boundary Convention, Fort Laramie Treaty

Shell Creek (on the Fort Berthold Reservation), North Dakota

September 20, 1946

Chairman Clarkes Burr; John W. Smith, Secretary

This is not the first time that public interest has sought to acquire the lands of the Fort Berthold Indians. It has been done before in the 1866 treaty which opened the territory for railroads, and by subsequent Executive Orders of 1870 and 1880, which reduced some more of our territory without our consent, until now we have only 600,000 acres left of the original 9,000,000 acres. Is that not depreciation enough? No. The public demands some more.

From testimony of Martin Cross, Hidatsa

April 30, 1949

Washington, D.C.

We go back to our ancestors and we go back to the treaties that they’ve established. When we go to Congress, the United States Senate, and the House of Representatives, and to the White House, we talk about our treaties because that’s what our ancestors signed. That’s what our ancestors died for, was to give us our treaties, and this includes our present-day holdings. We live by them and we’ll continue to make sure the Federal Government abides by our treaties. We will have a celebration of our treaty signing in 2001.

Tex Hall, Chairman

Commenting on the Sesquicentennial of the Fort Laramie Treaty

to be held in September 2001

Photo Gallery

Independence Valley

Documentary Photo, ca. 1953

North Dakota Heritage Center.

The people who had established Like-A-Fishhook village in 1845 began to look elsewhere about 1885. The Arikara moved to the vicinity of Nishu, the Mandans settled around the villages of Red Butte and Charging Eagle; the Hidatsa congregated around Shell Creek and Independence. The very name, Independence, stood for the Indians’ commitment to self-help, and to independence from the government agency, the mission, and white influences in general.

Source

Carolyn Gilman and Mary Jane Schneider, The Way to Independence: Memories of a Hidatsa Indian Family, 1840-1920 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1987), 186, 196.

Elbowoods

Documentary Photo of Elbowoods After Evacuation

North Dakota Heritage Center.

Water Rising

Elbowoods, North Dakota

State Historical Society of North Dakota, 194-10.

A Landmark

Saddle Butte

Calvin Grinnell photo.

Four Bears Bridge Over the Narrows near New Town

Calvin Grinnell photo.

This structure once spanned the Missouri River near Elbowoods.

Four Bears Bridge in a January Dawn

J. Agee photo.

Trail to Nightwalker’s Village

Calvin Grinnell photo.

The Hidatsa chief, Nightwalker, established a fortified butte-top village here around the time of the smallpox epidemic of 1781.

View from Nightwalker’s Village

Calvin Grinnell photo.

Mandan Indian Ferry on the Upper Missouri River

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1904

From Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1806 (2 vols. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), Plate 28.

Mandan Earth Lodge in Winter

(reconstruction)

Photo by J. Agee.

Holding Eagle’s Lodge

An Original

North Dakota Heritage Center, No. 86–1016.

This lodge was photographed about 1910. Short River, now Short Creek, enters the Missouri River a few miles downstream from Williston, North Dakota.

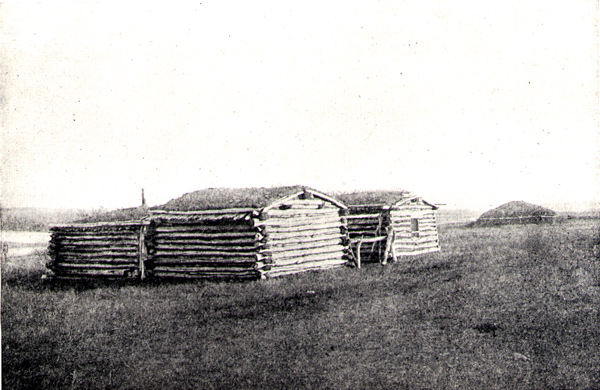

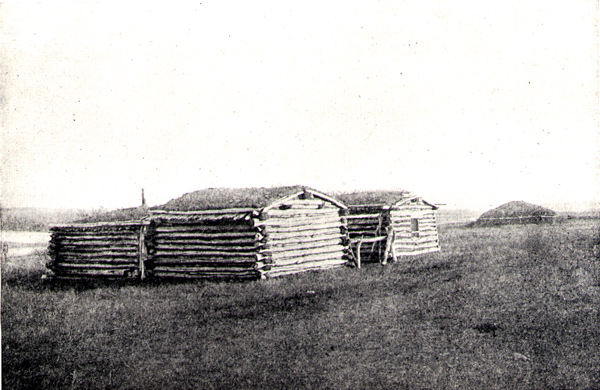

The Old Log houses on the Fort Berthold Reservation in 1904

From Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1904

(2 vols., New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 1:271.

A traditional earth lodge is in the background.

Mandan Indian Ferry on the Upper Missouri River

Fort Berthold Reservation, 1904

From Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1806

(2 vols. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), Plate 28.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.