Shannon, R. Field, and Colter

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

Youngest Enlisted Man

George Shannon, youngest enlisted man of the permanent party, suffers from an exaggerated reputation as a fool who was always getting lost and losing things. Yes, he was separated from the men twice–the first of these setting the Corps’ record for number of days alone—but the second time he did nothing wrong, and both times he made reasonable efforts not only for his own survival but also to rejoin the command. In 1807 he was seriously wounded in a battle with the Arikara Indians. He went on to a legal career, and while studying law on his own, he assisted Nicholas Biddle in preparing the latter’s paraphrase of the journals.

Shannon, a Pennsylvanian whose family had moved to the Ohio frontier in 1800, was one of the first men to volunteer for the expedition. Along with John Colter, he joined Capt. Lewis on a trial basis when the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) stopped at Maysville, Kentucky, in early October 1803. Shannon formally enlisted in the army on 19 October 1803, four days after Colter.[1]Moulton, ed., Journals, 1:521.

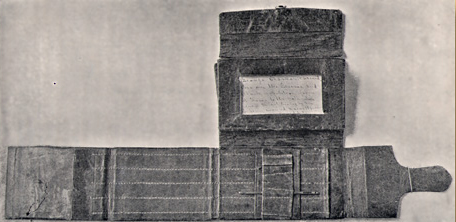

Housewife (Sewing Kit)

Collection of the Oregon Historical Society, No. 4014. From Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

This “housewife,” or sewing kit, George Shannon reportedly carried on the Lewis and Clark expedition is mad of leather dyed red on the outside, green on the inside.

Dimensions: 7-1/2 by 15 3/8 inches (open)

Lost

Shannon’s solo 16-day adventure began on August 26, 1804, near present Vermillion, South Dakota, when he and George Drouillard were sent out to hunt for the expedition’s few horses.

The captains had instructed the two men to keep to the high ground and follow the boats up the river. Drouillard came back the next day, saying he had not seen the horses and had lost track of Shannon. Joseph Field and John Shields were sent out to look for them, again with no results. Just when Shannon’s footprints were found–ahead of the Corps and heading upstream from them–the Yankton Sioux were contacted, the expedition was not only behind him, but also had stopped.

On 28 August 1804, Colter was sent to track Shannon and bring him in. He spotted the, tracks of the young man as well as those of the two horses, but returned to the main party on 6 September 1804, after nine days, without Shannon or the horses. Meanwhile, Clark noted that Shannon, “not being a first rate Hunter”–a high standard among this select group of frontiersmen–created added concern.

The captains later learned that Shannon had found the horses, then “Shot away what fiew Bullets he had,” but failed to get any meat. Eventually, he carved a bullet from a stick and got a rabbit–his only food other than wild grapes during more than two weeks. Also, one of the horses wandered away as Shannon slept.

Finally, on 11 September 1804, the barge crew spotted a starving Shannon sitting listlessly on the Missouri River bank, in hope of being rescued by some fur traders. Clark marveled that “thus a man had like to have Starved to death in a land of Plenty for want of bulletes or Something to kill his meat.”

Thereafter, all the men understandably had reservations about Shannon’s reliability as a woodsman. At White Bear Islands on 19 June 1805, while Clark was busy setting up the portage from the lower camp, Lewis dispatched Shannon, along with George Drouillard and Reubin Field to hunt elk on the Medicine River. Somehow Shannon got separated from the other two hunters, although five days late Lewis had no trouble finding his camp, from which Shannon had killed no elk but had bagged “seven deer and several buffaloe and dryed about 600 lbs. of buffaloe meat.” Meanwhile Reubin Field had made his way to the lower portage camp and “informed Capt. Clark of the absence of Shannon, with rispect to whome they were extreemly uneasy.” The apparent crisis had arisen simply because of the slowness of communication.

Lost Again

The next time Shannon was “lost,” in early August 1805, Clark sent him hunting up the Big Hole River in southwestern Montana.[2]Ibid., 5:55. Evidently Clark believed Shannon had improved his skills as a woodsman during the eleven months since his first misadventure. Clark mistakenly believed the Big Hole to be the Jefferson River‘s feeder source from higher in the Rockies. Shannon was to hunt a few miles up the Big Hole and watch for the canoes to catch up.

When Lewis subsequently arrived at the forks of the Jefferson, he correctly chose the Beaverhead River as the fork to follow. His main party connected with Clark’s advance party, and the combined Corps prepared to move up the Beaverhead. On 6 August 1804, Lewis “had the trumpet sounded and fired several guns,” but there was no response. On the 7th, Reubin Field was sent to inform Shannon of the route change; he returned later the same day, having seen nothing of the younger private.

But Shannon found the Corps on his own on 9 August 1804, arriving with the hides of three deer he had killed while trying to locate his comrades. When they did not catch up to him, he returned to the forks. Since they weren’t there, he had turned back up the Big Hole again and “marched” for a full day, going high enough into the mountains to see that the Big Hole was unnavigable. Then he figured that everyone must have decided to follow the other fork, so he returned there and started up the Beaverhead. He had not been lost, just left out in the field without necessary information. Well fed, but very weary.

Shannon demonstrated the great improvement in his marksmanship, to Nathaniel Pryor‘s and Richard Windsor‘s relief, on 26 July 1806. Shannon was in Nathaniel Pryor’s group of four (the fourth being Hugh Hall) herding Lemhi Shoshone, Salish, and Nez Perce horses toward Canada to trade for supplies and assistance. The horses had been taken by Indians the night before, and the men were now traveling by quickly-constructed bull boats—hoping to catch up with the expedition but content that the Missouri would take them to St. Louis. A wolf sneaked into their camp and bit Pryor’s hand while he slept, then made to attack Windsor. Shannon shot the beast before more harm was done.

Biddle’s Able Assistant

Clark arranged for Shannon to assist Nicholas Biddle in editing the expedition’s journals, which were completed in 1812. Regarding Shannon’s abilities, Biddle wrote to Clark: “I have derived much assistance from that gentleman who is very intelligent and sensible & whom it was worth your while to send here.” Judging from Clark’s expressions of confidence in Shannon, and Shannon’s subsequent record as an attorney, he must have been one of the most literate of all the men in the Corps.”

Disabled Vet

When the Corps of Discovery left the Knife River Villages on the 18 August 1806, en route home, they had two distinguished passengers in the red pirogue—the Mandan chief, Sheheke , also known as “Big White,” and his wife, Yellow Corn. They had accepted the captains’ invitation to accompany them to the United States to visit President Jefferson. In the fall of 1807, Nathaniel Pryor, now with the rank of ensign, was in command of the party of soldiers responsible for escorting the Mandan chief and his wife home. That party included George Shannon. Unfortunately, they were stopped by a band of Arikara warriors, and a running battle ensued. One of the three Americans wounded that day, some 1,300 miles up the Missouri River, was twenty-two-year-old George Shannon.

On 11 October, more than four weeks after suffering his wound, Shannon reached Bernard B. Farrar, a St. Louis physician, who signed an affidavit describing the patient’s condition: “I found one of his legs in a state of gangrene caused by a ball having passed through it, and that to save his life I was under the necessity of amputating the limb above the knee, the loss of which constitutes in my opinion the first grade of disability.” In view of his disability, and in accordance with the provisions of the First Amendment to the Constitution,[3]“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Shannon had the right to petition Congress for a pension. With Clark’s help he won his case in 1814, seven years after the battle, receiving only eight dollars per month.

Three years later Clark wrote a letter to Henry Clay, the speaker of the House of Representatives, in support of Shannon’s petition for an increase, calling him “one of the most active and useful men” under his command on the expedition to the Pacific. Clark asserted that he himself, as agent for the government, had hired Shannon in 1807 “to accompany and assist the Mandan Chief on his return to his Nation, . . . for which he was to receive Twenty five Dollars per Month.” As to the amount of the pension, he concluded, “I conceive Mr. Shannon justly entitled to, at least one half of the Salary he was receiving from the government, at the time this misfortune befell him, which has occasioned his disability.”[4]Robert E. Lange, “Private George Shannon: The Expedition’s Youngest Member, 1784 or 1787–1836,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 8, No. 3 (August, 1982). At last, by another act of Congress in 1817, following almost ten years of struggle for fair treatment, his pension was increased to comparatively munificent twelve dollars per month. In March of 1822 Congress denied his petition for 640 acres of land as further compensation for his injury.

Law Career

George Shannon studied law more formally than many attorneys of the day, although he did not complete the two-year course at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. He left college during his second year, in 1810, when political change in Washington, D.C., temporarily cut off his pension. Shannon had continued to study law while working with Biddle, and afterward, then returned to Lexington to begin practicing later in 1812.

Shannon married the following year, and the couple had seven children. The law practice was reasonably successful, but suffered from cash-flow problems typical of frontier attorneys. In the early 1820s, he was elected to three successive one-year terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives–a career sometimes confused with that of his brother Thomas, who served in the U.S. House.

Appointed a circuit court judge soon after, he found himself on the bench as the governor’s son was tried for murder. When the man was convicted but the defense claimed that the jury had been influenced, Shannon set aside the verdict and ordered a new trial–displeasing both sides. With no future in Kentucky, the Shannon family moved west, to St. Charles, Missouri. Within a year George Shannon was serving as U.S. district attorney, by appointment of President Andrew Jackson.

In the major case of his career, Shannon served as one of three defense attorneys for the Iowa chief Big Neck in 1830. William Clark, as commissioner of Indian affairs, watched the case closely, along with much of the public. A skirmish had resulted between white settlers and Big Neck’s people when the whites attempted to enforce a treaty the chief had signed. No one could say who fired first, but all agreed Big Neck had been unarmed. Nevertheless, he and four other Iowas were arrested for murder. Shannon and the defense argued that the chief had not understood the treaty when he signed it. That and greatly conflicting testimony carried the day; the jury acquitted all five suspects without even retiring from the box.[5]Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 165-166.

Shannon ran for the U.S. House in 1833, and was defeated not two months after his wife’s death from typhus. After that, the man went downhill, drinking heavily and ruining his health. He was not reappointed U.S. district attorney in 1834. George Shannon died at the age of fifty-one in Palmyra, Missouri, where he had gone to defend a murder suspect.

Notes

| ↑1 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 1:521. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 5:55. |

| ↑3 | “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” |

| ↑4 | Robert E. Lange, “Private George Shannon: The Expedition’s Youngest Member, 1784 or 1787–1836,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 8, No. 3 (August, 1982). |

| ↑5 | Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 165-166. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.