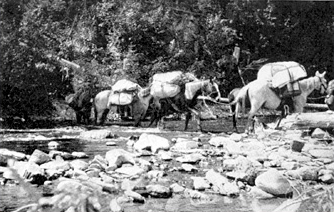

Pack Horses Cross Salmon River

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”

The Corps’ horses would not have been packed with loads as large as this, owing to the reported poor condition of the horses’ backs. Also, the horses would probably have been led one at a time, not in strings of two or more.

From Boats to Pack Horses

Back at Camp Fortunate on 18 August 1805, after Clark and his party left to explore the Salmon River as a direct waterway to the Pacific, Lewis “had all the stores and baggage of every discription opened and aired. and began the operation of forming the packages in proper parsels for the purpose of transporting them on horseback.” Clark’s hunters had killed one deer before they departed, and that evening Lewis “had the raw hides put in the water in order to cut them in throngs [thongs] proper for lashing the packages and forming the necessary geer for pack horses, a business which I fortunately had not to learn on this occasion.” Evidently several of the men still had a few lessons to learn.[1]On 24 August 1805, the day before leaving Camp Fortunate bound for the Pacific Coast, Lewis recorded details about Lemhi Shoshone horses and tack in The Shoshone Caparison

The next morning, while some of the men made much-needed leggings and moccasins, others were repacking the baggage, “making pack saddles &c.” Work continued until:

by evening the cash was completed unperceived by the Indians, and all our packages made up. the Pack-saddles and harnes is not yet complete. in this operation we find ourselves at a loss for nails and boards; for the first we sugstitute throngs of raw hide which answer verry well, and for the last to cut off the blades of our oars and use the plank of some boxes which have heretofore held other articles and put those articles into sacks of raw hide which I have had made for the purpose. by this means I have obtained as many boards as will make 20 saddles which I suppose will be sufficient for our present exegencies.

Loading and Handling

Loading and handling a pack horse is hard work. It demands not only a great deal of physical strength and endurance, but also an eye for balancing a load on the first try, a head full of horse sense, the patience of a saint, and lots of experience. Additionally, some folks say, a well-practiced vocabulary of uncomplimentary epithets seems to soothe the wrangler, and doesn’t offend a horse at all. Any of those qualifications that some of the men of the Corps may have lacked when they arrived at Camp Fortunate–fresh off the boat, so to speak–were probably remediated by the time they reached the Bitterroot Divide. The spirit of teamwork they had developed as boatmen in the crucible of the lower Missouri River in the summer of ’04 must have powered them through this new learning curve quite handily.

Above is a pack saddle of the type that the Corps of Discovery may have built. It is called a “sawbuck” because of its resemblance to the device used to steady a log while sawing it into firewood lengths. Cargo is securely roped to the X-shaped uprights. This late-19th-century example, assembled with rivets, is shown with steel fittings and stitched leather rigging. The sawbucks the Corps built out of boards salvaged from wooden crates, nailed and raw-hided together, may have been of much lighter construction, but they only had to last for two trips across the Bitterroot Mountains.

A Secret Cache

On 20 August 1805 Lewis took three men down “Jefferson’s River,” today’s Beaverhead, about three-quarters of a mile and “scelected a place near the river bank unperceived by the Indians for a cash [cache],” and “directed the centinel to dischage his gun if he pereceived any of the Indians going down in that direction which to be the signal for the men at work on the cash to desist and seperate, least these people should discover our deposit and rob us of the baggage we intend leaving there.”

For the sake of safety and efficiency, horse packing also requires the best of equipment–a well-fitted pack saddle, a strong, broad girth that won’t gall the animal’s belly; and a breeching—a rope or leather strap around the horse’s haunches—to keep the pack saddle and its load from riding up over the withers. Above all, it wants ropes that will hold a knot without slipping, yet will untie quickly in an emergency.[2]Clark “Purchased pack Cords” from a Shoshone supplier on the 30th, but left no clues as to the materials or workmanship. The Corps evidently started out with the simple equipment … Continue reading Nevertheless, these men were accustomed to making do with the best they could make, and all we can be sure of is that they made their best.

Leading a horse up or down steep mountain slopes is extremely exhausting and potentially hazardous to the leader.[3]From the mouth of the North Fork of the Salmon (elevation 3620 ft) to Lost Trail Pass (el. 7014 ft) the men and horses had to climb 3,394 feet in 20 miles. The last few miles before reaching the … Continue reading The horse lurches and leaps, sees and seizes routes sometimes faster than a man can move out of the way. Meanwhile, a horse is a solar-powered eating machine that needs at least 25 pounds of equine edibles per day, day and night, with scarcely a pause. Even while working, a horse is adept at snatching snacks of leaves and grass on the run, sometimes jerking the lead-shank (rope) out of the wrangler’s hand.

Dangers

Unfortunately, the two-legged critter can’t afford the distraction of eating or drinking on the run. Besides, keeping a heavy pack secure on a lunging horse’s back in rough terrain becomes a man’s overriding concern. That, and the need to guide the horse away from broken stumps of limbs—called “stabs” (horsmen say “stahbz”)—on downed trees, which can puncture the horse’s belly. There are no records of such accidents during the climb out of the Salmon River valley, but on the return trip over the Bitterroot Mountains, Pierre Cruzatte‘s horse “snagged himself so badly in the groin in jumping over a parsel of fallen timber” that he was useless thereafter. Also, pack horses (as opposed to mules) seem to have no feeling for how wide their loads are, and bang into every trailside tree without learning a thing.[4]Clark reported on 3 September 1805 that they had “met with a great misfortune, in haveing our last Thmometer [thermometer] broken by accident.” However, the month’s record of … Continue reading Indeed, when the Corps crossed the Bitterroot Mountains during a snowstorm on 16 September 1805, Clark noted, “we had in many places to derect our Selves by the appearence of the rubbings of the [Indians’] Packs against the trees.”

The journalists haven’t left us many details about the qualities of their 29 or 30 head of livestock, including one or two mules, which they bought from the Shoshones.[5]Patrick Gass estimated that their remuda cost them a total of about $100 in trade goods. Clark merely remarked (30 August 1805) that “we cannot Calculate 150-160 pounds per animal, or a total of no more than about 4,000 pounds. At that rate, each man would have to carry some duffel on his own back. On the other hand, Clark added, “The horses are . . . much acustomed to be changed as to their Parsture.” That is, they weren’t inclined to head for home the minute they were off the job. In a horseman’s lingo, they weren’t “barn-sour.”

Notes

| ↑1 | On 24 August 1805, the day before leaving Camp Fortunate bound for the Pacific Coast, Lewis recorded details about Lemhi Shoshone horses and tack in The Shoshone Caparison |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Clark “Purchased pack Cords” from a Shoshone supplier on the 30th, but left no clues as to the materials or workmanship. The Corps evidently started out with the simple equipment necessary for a “rope walk.” They called their camp of 17–18 June 1804, near Waverly, Missouri, “Rope Walk Camp” because there they made 600 feet of rope, according to Private Whitehouse. More than likely they would have had the same tools with them at Camp Fortunate, since rope was essential to the maintenance and navigation of their watercraft, and they had expected to have use horses for the portage. However, there is no mention of a rope walk there. (see also Making Rope) |

| ↑3 | From the mouth of the North Fork of the Salmon (elevation 3620 ft) to Lost Trail Pass (el. 7014 ft) the men and horses had to climb 3,394 feet in 20 miles. The last few miles before reaching the ridge were of course the steepest. |

| ↑4 | Clark reported on 3 September 1805 that they had “met with a great misfortune, in haveing our last Thmometer [thermometer] broken by accident.” However, the month’s record of morning and afternoon temperature readings continued through 4:00 p.m. on 5 September 1805. Indeed, Clark noted in the daily remarks for September that the instrument was indeed broken on 6 September 1805 “by the Box strikeing against a tree.” Moulton, Journals, 5:241. |

| ↑5 | Patrick Gass estimated that their remuda cost them a total of about $100 in trade goods. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.