International Competition

Figure 1

A French-Canadian Trapper

Frederic Remington

Courtesy Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

French-Canadian traders had operated on the Missouri River from bases on the Assiniboine and other rivers beginning in the 1780s, and others joined the American Fur Company and its competitors after that company entered the upper Missouri fur trade.

The Corps of Discovery had been, as James Ronda phrased it, “only the latest in a long series of traders and travelers” to visit the tribes living along the Missouri.[1]James P. Ronda, Lewis & Clark Among the Indians, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; bicentennial edition, 2002), 67. All that distinguished Lewis and Clark’s expedition was the number of men in the group and the size of their military barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’)—all other visitors from downriver had traveled in far more modest pirogues or in bull boats, or they had come overland. French voyageurs and, later, English traders had been visiting the Omaha and Iowa Indians and their neighbors on foot from Prairie du Chien and other points on the Mississippi River even before 1718.

The Mandans had been visited, overland, from the north in 1738 by Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, the Sieur de la Vérendrye, from his base on the Assiniboine River. Visitors coming up the Missouri, however, were rare until 1797, when John Thomas Evans arrived among the Mandans as part of an expedition sponsored by Spanish merchants in St. Louis. He was told to establish trading relations with the Missouri River Indians but, equally important, he was directed to expel British traders from a post they had established near the Mandans.

That post had been built by the North West Company of Montreal to compete with Hudson’s Bay Company traders for the Mandan and Hidatsa trade—an overland trade that had begun in the 1780s—and it was part of Upper Louisiana in which Spain was claiming that trade for itself.

Lewis and Clark had entered a region rife with competition between French, English, and Spanish traders for their Indian customers. The Louisiana Purchase had made American citizens of the St. Louis French and Spaniards, and the attempt began to evict English traders not only from this new American territory, but from their old haunts in the Old Northwest as well.

Road of the Voyagers

Guillaume Delisle (1675-1726) was one of the foremost French cartographers of the early eighteenth century. His charts included the most thoroughly researched and meticulously drafted representation of North America available as of 1718.[2]W. Raymond Wood, “Early Maps of the American Midwest,” The Living Museum 64, No. 1 (2002): 3-4. This excerpt from that map, for example, includes the overland route from Prairie du Chien to the Omaha and Iowa villages, which French and British Canadian traders had been using for some years.

Mackay and Evans Expedition

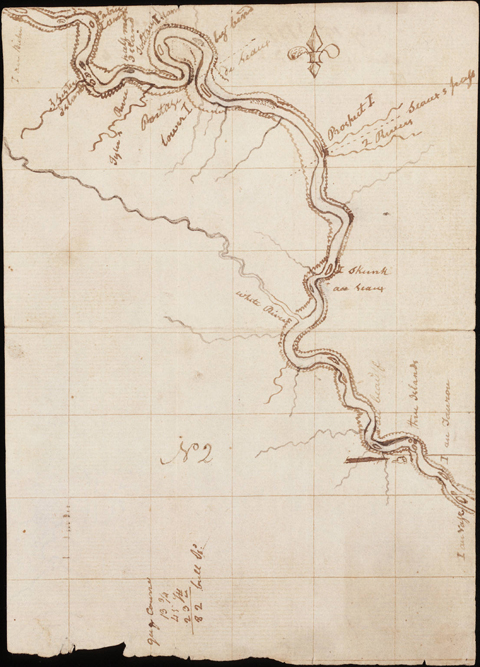

In 1795 Spanish merchants in St. Louis had sent James Mackay and John Evans on a trading expedition up the Missouri River with instructions to find a route to the Pacific Ocean. Between 1795 and their return in 1797 they produced a set of maps (Figs. 2, 3, 4) that charted the river from its mouth to the Mandan villages, and that gave names for all of its principal tributaries. French voyageurs almost certainly had given the explorers the names they’d attached to these streams—names that, for the most part, they still bear. The maps laid out in detail the first full year of the Lewis and Clark expedition and were important planning documents for the Captains.

This section (Fig. 3) of the Mackay/Evans map extends from the island at lower right called “au Vase”–now submerged beneath Lake Francis Case, the reservoir behind Fort Randall Dam in southeastern South Dakota–to “I au Biche,” which the Corps of Discovery may have reached on about 24 September 1804.

Expectantly, on 14 September 1804 both of the captains “walked on Shore with a view to find an old Volcano, Said to be in this neighbourhood by Mr. McKey.” They didn’t find the volcano, of course, but made two discoveries of exceptional importance: Clark shot the expedition’s first pronghorn antelope and wrote a short description of it, and Lewis wrote a detailed account of the first specimen of the white-tailed jackrabbit (See NE Nebraska Minerals and Hares and Jackrabbits) he had first heard of from Chouteau in St. Louis.

Five days later the Corps camped on the “lower I” at the downriver end of the Big Bend, which had been a major landmark for travelers on the Plains for almost a century.

Notes

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.