As he waits in Pittsburgh for the military barge to be completed, Lewis leaves little record of his day-to-day activities. The Ohio River boatmen he encountered there were described by other travelers.

Flatboat Men

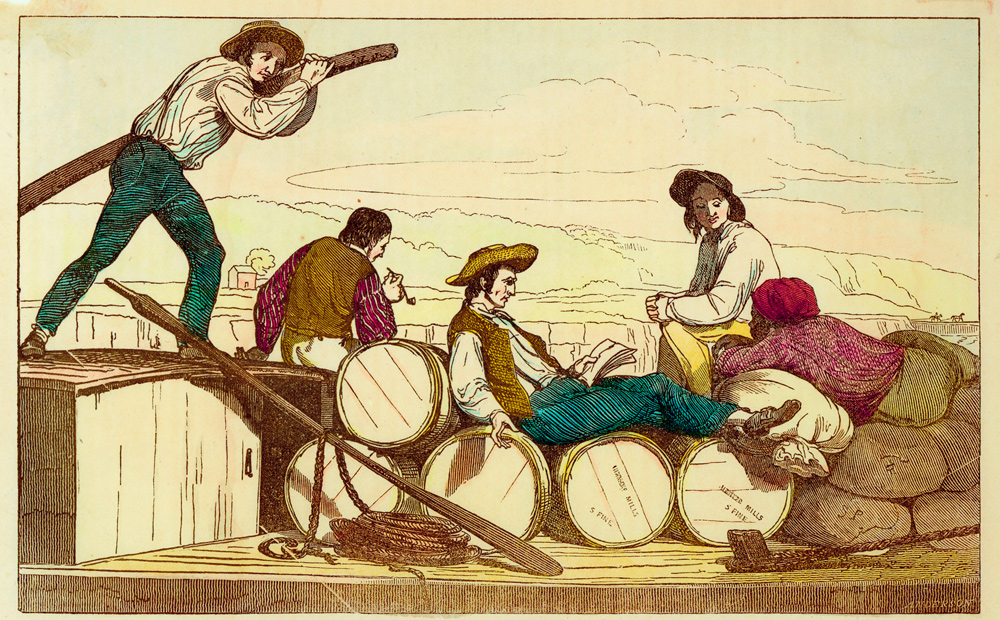

“Flatboatmen relaxing on their cargo” likely by Alexander Anderson, 1775–1870. Courtesy Missouri History Museum, N22055.

The Barge-Man Circuit

The major part of the merchants settled at Pittsburgh, or in the environs, are the partners, or else the factors, belonging to the houses at Philadelphia. Their brokers at New Orleans sell, as much as they can, for ready money; or rather, take in exchange cottons, indigo, raw sugar, the produce of Low Louisiana, which they send off by sea to the houses at Philadelphia and Baltimore, and thus cover their first advances. The barge-men return thus by sea to Philadelphia or Baltimore, whence they go by land to Pittsburgh and the environs, where the major part of them generally reside.

—François André Michaux[1]François André Michaux, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains (1805 reprint from London edition), p. 61–2 in Reuben G. Thwaites, Travels West of the Alleghanies (Cleveland: The Arthur H. … Continue reading

Ohio River Flatboat Men

After traveling down the Ohio River in a skiff in 1894, historian Reuben Gold Thwaites said this of the first Ohio River boatmen:

As for the boatmen who professionally propelled the keels and fiats of the Ohio, they were a class unto themselves—”half horse, half alligator,” a contemporary styled them. Rough fellows, much given to fighting, and drunkenness, and ribaldry, with a genius for coarse drollery and stinging repartee. The river towns suffered sadly at the bands of this lawless, dissolute element. Each boat carried from thirty to forty boatmen, and a number of such boats frequently traveled in company. After the Indian scare was over, they generally stopped over night in the settlements, and the arrival of a squadron was certain to be followed by a disturbance akin to those so familiar a few years ago in our Southwest, when the cowboys would undertake to “paint a town red.” The boatmen were reckless of life, limb, and reputation, and were often more numerous than those of the villagers who cared to enforce the laws; while there was always present an element which abetted and throve on the vice of the river-men. The result was that mischief, debauchery, and outrage ran riot, and in the inevitable fights the citizens were generally beaten.[2]Reuben Gold Thwaites, On the Storied Ohio: An Historical Pilgrimage of a Thousand Miles in a Skiff, from Redstone to Cairo (Chicago: A. C. McClug & Co., 1903), 164–65.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to August 22, 1803:

Notes

| ↑1 | François André Michaux, Travels to the West of the Alleghany Mountains (1805 reprint from London edition), p. 61–2 in Reuben G. Thwaites, Travels West of the Alleghanies (Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904), p. 159. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, On the Storied Ohio: An Historical Pilgrimage of a Thousand Miles in a Skiff, from Redstone to Cairo (Chicago: A. C. McClug & Co., 1903), 164–65. |