Photo by David E. Nelson

Research Associate Professor, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology

Bob Bergantino owes his interest in Lewis and Clark to his father, who was a surveyor for the U.S. Corps of Engineers at Fort Peck during the 1930s. Bob earned a degree in geology at the University of Montana, meanwhile gaining experience as a surveyor along the Missouri River in Montana and North Dakota, and then worked with the U.S. Navy Oceanographic Office in Washington, D.C., making bathymetric and seismic surveys, and mapping the sea floor. In 1974, he and his family moved to Butte, Montana, where he was hired as a hydrogeologist by the Bureau of Mines and Geology at Montana Tech.

In 1970, as a hobby, he and his wife Sharon studied the escape route of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and corrected some historical misperceptions. Next, drawing upon his interests, education, and experience, Bob set out to map the Lewis and Clark survey points, routes and campsites through Montana, steadily refining his conclusions with the maps and aerial photos available at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. He also mapped the portage route around the Falls of the Missouri.

Beginning in 1986 Dr. Bergantino was engaged in preparing the basic texts for the geologic and geomorphic footnotes for Gary E. Moulton’s new edition of the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and assisted in locating campsites and identifying creeks and other geographic features mentioned in the journals.

At about the same time he became greatly interested in the Expedition’s celestial observations. He eventually recalculated all their conclusions regarding latitudes, extended the data they collected for longitudes, and also mapped magnetic declinations for the explorers’ entire route.

In 1991 Dr. Bergantino provided the National Park Service with a database of the campsite coordinates from Wood River to Fort Clatsop and return. In 2002, he completed a GIS-compatible database of the entire Lewis and Clark route through Montana, for the Continuing Education at the University of Montana, as a resource for teaching map interpretation, and a basis for further research.

Contributions

After the expedition, the Three Forks area would see the death of Potts and Drouillard, the start of Colter’s famous run, and an emerging frontier lifestyle in Gallatin City, later to be known as Three Forks, Montana.

Pryor and six privates had successfully driven forty-one horses all the way to the Yellowstone Valley, apparently without any trouble. Then, smoke on the horizon. Twenty-four horses stolen on the twentieth. Seventeen taken on the twenty-fifth.

Determining the latitude of a location from a meridian observation of the sun is among the simplest celestial observations to take and to calculate. On 5 October 1805, Clark writes: “Latitude of this place from the mean of two observations is 46°34’56.3″ North.”

Jefferson’s Debt Paid at Last

Introduction to "Deciphering the Celestial Data"

by Robert N. Bergantino

Lewis and Clark made celestial observations at “all remarkeable points on the rivers.” Hassler was selected to complete the longitude calculations from that data, but he never finished the job. Jefferson was not satisfied.

Lewis and Clark sometimes called this coal “carbonated wood” because sometimes they could see the outlines of woody stems and other plant remains. Coal geologists call it lignite, but Lewis and Clark were essentially correct in their description.

Deciphering the Celestial Data

by Robert N. Bergantino

Lewis and Clark made celestial observations at “all remarkeable points on the rivers.” Hassler was selected to complete the longitude calculations from that data, but he never finished the job. Jefferson was not satisfied.

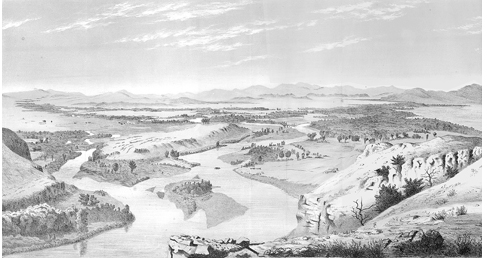

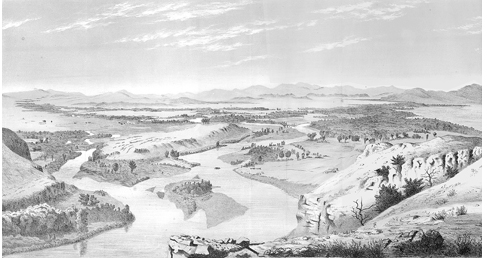

On 1 August 1805, Clark and the expedition’s flotilla of eight dugout canoes pushed up the Jefferson River through “a verrey high mountain which jutted its tremendious Clifts on either Side for 9 Miles, the rocks ragide.” They emerged into a “wide exte[n]sive vallie.”

On 28 July 1805, while a fever-ridden Clark drew maps, Lewis began his celestial observations. By late night on 29 July, Lewis had completed ten discrete celestial observations consisting of a total of forty-eight separate angular measurements.

Clark evidently began compiling a map of the Northern Rockies after meeting with Hugh Heney at Fort Mandan on 18 December 1804, and continued adding information acquired from other traders, as well as from Indians. The reality, he would find, was much different.

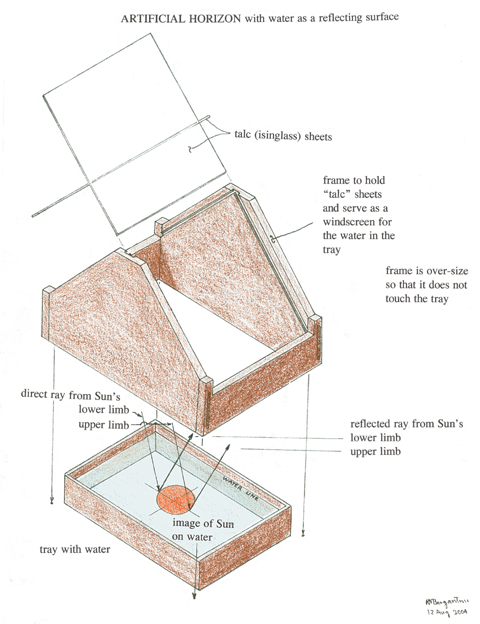

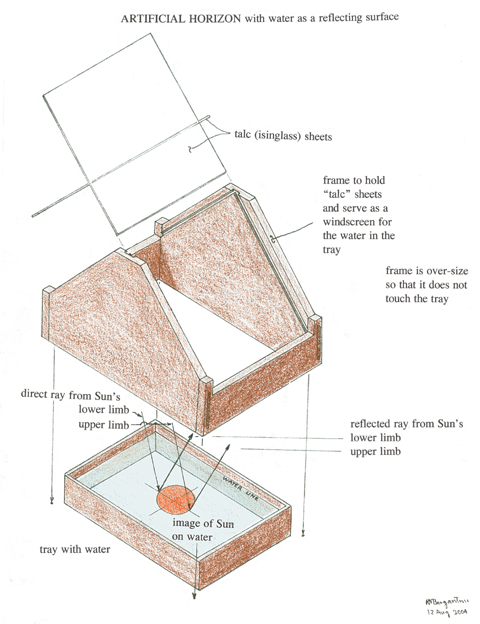

The morning of 16 November 1805 dawned “Clear and butifull.” At noon Clark took advantage of the conditions and made an observation of the sun’s altitude for latitude. He used the sextant and artificial horizon.

On 17 October 1805, at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers, Lewis set out the artificial horizon and got the sextant out of its case. One of the men stood by with the chronometer, ready to read and record the time of Lewis’s measurements.

If, as suggested, Fortunate Camp was at 44°59’36″N, how did Lewis, after averaging four observations, come up with a latitude 24 minutes too far south?

“at this place there is a large rock of 400 feet high wich stands immediately in the gap which the missouri makes on it’s passage from the mountains.”

Lewis’s simple, orderly concept of the Rocky Mountains began to crumble. The truth was, this was not the easy portage to the Pacific Ocean they had expected from the beginning. Countless “chains” of mountains still intervened.

The lignite in the Fort Union Formation ignites easily. Sometimes the materials adjacent to the burning coal beds become so hot that they actually froth and, when cooled, resemble the bubbly and cratered volcanic rock called pumice.

An analysis of Lewis’s celestial observations made during their stay at Long Camp near present-day Kamiah, Idaho.

It was a clear night. The moon, just two days short of its first quarter, was 23° above the horizon bearing S78° W when the captains began their observations about 9:30 p.m.

Lewis’s remarks about the comparative suitability of the three horizons used to observe stars—one using water and two with mirrors—are analyzed and illustrated by Robert N. Bergantino.

Celestial observations at the Kansas and Missouri river confluence began shortly after 8 a.m. on 27 June 1804. The first observation would provide the data necessary to calculate the magnetic declination.

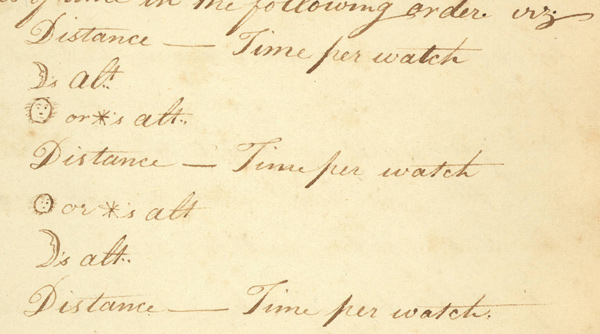

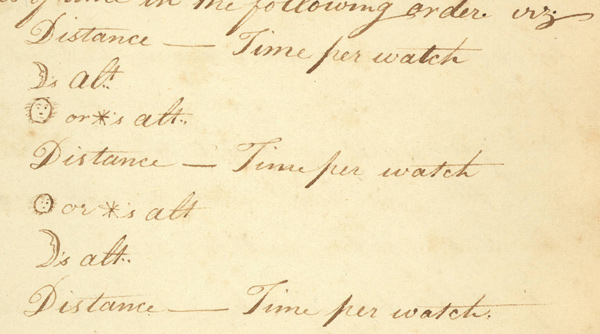

Known now as the “Astronomy Notebook,” this extraordinary document has been an obscure and often neglected detail in the history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Transcribed in full with commentary by Robert Bergantino.

The Fort Union Formation

by Robert N. Bergantino

Today it is a high and dry plain, but sixty million years ago it was a shallow saucer in the earth’s crust, filled with warm, steamy tropical jungles. That rich, dense vegetation would, over some millions of years, become a huge, complex deposit of lignite.

Before arriving at the three forks of the Missouri, Whitehouse wrote that they “passed some rough rockey hills, which we expect from the account we have from the Indian Woman that is with us, to be the commencement of the Second chain of the Rockey Mountains.

Late in the day on 19 July 1805, Lewis and his party entered a canyon between “the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen.” They seemed to rise “from the waters edge on either side perpendicularly to the hight of 1200 feet.”

Pumice Stone

by Robert N. Bergantino

“The Pumies Stone which is found as low as the Illinois Country is formed by the banks or Stratums of Coal taking fire and burning the earth imedeately above it into either pumies Stone or Lavia. This Coal Country is principly above the Mandans.”

In January 1798, Thompson took celestial observations at the villages and determined them to be at a latitude of 47°17’22″N and a longitude of 101°14’24″W. Why then did Lewis and Clark think it necessary to take twenty-six observations?

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.