Lewis’ Description

“Snags (sunken trees) on the Missouri” [cropped]

by Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Snags (im Missouri versunkene Baumstämme). Snags (troncs d’arbres obstruant le cours du Missouri). Snags (sunken trees on the Missouri).”[1]New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 20 July 2024, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c42f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Original from Voyage dans l’intérieur de … Continue reading

The Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, who was employed by Prince Maximillian von Wied (1809–1893) to accompany him on a journey to the upper Missouri River, painted this primeval forest of grotesque limbs reaching up from the dark water to grapple the side-wheeler Yellow Stone into submission, and submersion. The artist’s macabre sense of humor is reflected by that lumpy black spot poised on the tip of the snag at extreme left. A closer look reveals it to be a turkey vulture–hungrily awaiting the carrion to come.

On 31 March 1805, Meriwether Lewis wrote a long letter to his mother, Lucy Marks, from Fort Mandan detailing the daunting dangers he had faced on the Missouri River, and hinting at the anxiety that, even as a natural risk-taker, he was feeling in anticipation of rivers to come:[2]Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 222–25. The original letter is at the Missouri … Continue reading

So far, we have experienced more difficulty from the navigation of the Missouri, than danger from the Savages. The difficulties which oppose themselves to the navigation of this immence river, arise from the rapidity of it’s current, it’s falling banks, sandbars, and timber which remains wholy, or partially concealed in it’s bed, usually called by the navigators of the Missouri and Mississippi Sawyers or planters.

One of those difficulties, the navigator never ceases to contend with, from the entrance of the Missouri to this place; and in innumerable instances most of those obstructions are at the sam[e] instant combined to oppose his progress, or threaten his distruction. To these we may also add a fifth and not much less inconsiderable difficulty, the turbed quality of the water, which renders it impracticable to discover any obstruction even to the debth of a single inch.

Such is the velocity of the current at all seasons of the year, from the entrance of the Missouri, to the mouth of the great river Platte, that it is impossible to resist it’s force by means of oars or poles in the main channel of the river; the eddies therefore which generally exist one side or the other of the river, are saught by the navigator; but these are almost universally incumbered with concealed timber, or within the reach of the falling banks, but notwithstanding are usually preferable to that of passing along the edges of the sand bars, over which, the water tho’ shallow runs with such violence, that if your vessel happens to touch the sand, or is by any accedent turned sidewise to the current it is driven on the bar, and overset in an instant, generally distroyed, and always attended with the loss of the cargo.

The base of the river banks being composed of a fine light sand, is easily removed by the water, it hapens that when this capricious and violent current, sets against it’s banks, which are usually covered with heavy timber, it quickly undermines them, sometimes to the debth of 40 or 50 paces, and several miles in length. The banks being unable to support themselves longer, tumble into the river with tremendious force, distroying every thing within their reach.

The timber thus precipitated into the water with large masses of earth about their roots, are seen drifting with the stream, their points above the water, while the roots more heavy are draged along the bottom untill they become firmly fixed in the quicksands which form the bed of the river, where they remain for many years, forming an irregular, tho’ dangerous chevauxdefrise

Lewis’s Frisian Horses

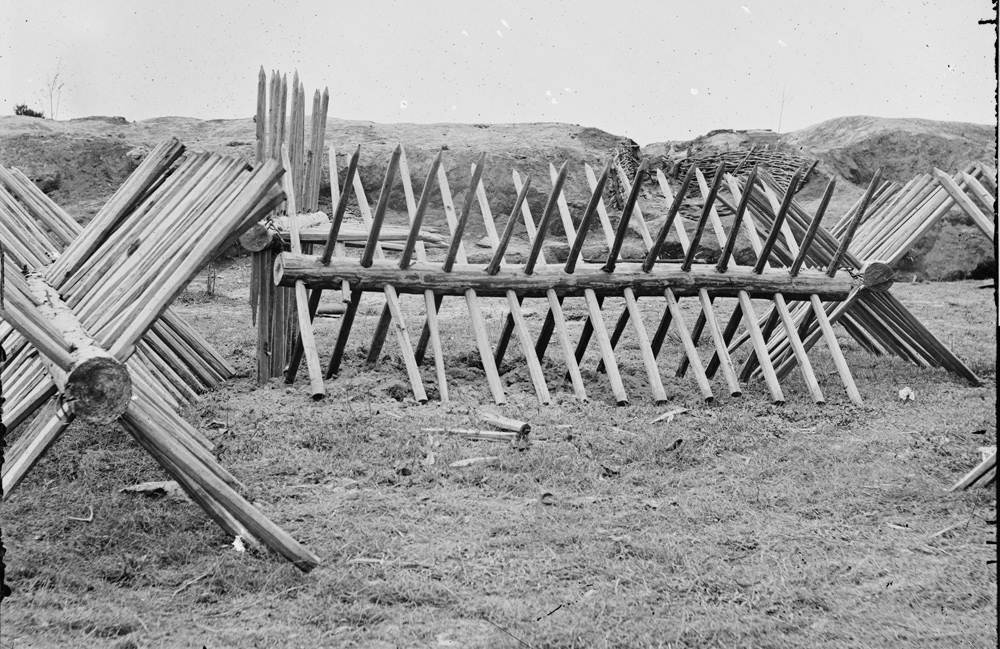

Cheval défriser, Lewis’s Frisian Horse

Sections of a Cheval défriser before the Confederate main works. From a 1865 glass plate negative created at Petersburg, Virginia. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpb-02597, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018666710/

Lewis’s metaphor was an apt choice. Properly cheval défriser (singular; plural, cheveux), the phrase denoted a “Frisian horse”, a nickname for a medieval defensive obstacle commonly employed against enemy cavalry ashore by the seagoing Frisian people, who occupied the North Sea Coast from the Netherlands to the border of Denmark. Variants of the cheval défriser were used in the American Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and in the defenses of some Pacific Islands during World War II.

Snags and Sawyers

Sometime in the more or less distant past, springtime floodwaters deposited rich loam on the floodplain here, then ran on downhill toward the Gulf of Mexico. At the water’s margins cottonwood trees, Populus deltoides like those in the figure took root in the hospitable soil, reaching down to drink, holding on for dear life.

Annually, the river sips away at the banks and claims what it left on them back then. In due time the cottonwoods succumb to the river’s subversion, lie down in the depths and die, and become snags. They are submarine sieves, straining through their flailing limbs and naked rootwads all the flotsam the river brings their way. Sometimes, even today, they trap boats and, occasionally, boaters. They are open manholes on the riverine roadways of the West.

All the snags’ branches wave under the water much as they blew in the wind. Those that protrude above the river’s surface also oscillate in the current, as if to warn sensible creatures away. These are called sawyers.

Captain Lewis recorded an encounter that Sergeant Ordway and Private Willard had with a gang of sawyers on the night of 4 August 1806, somewhere downstream from the mouth of the Milk River:

Ordway and Willard delayed so much time in hunting today that they did not overtake us untill about midnight. . . . In passing a bend just below the gulph, it being dark, they were drawn by the currant in among a parsel of sawyers, under one of which the canoe was driven and throwed Willard who was steering overboard. He caught the sawyer and held by it. Ordway with the canoe drifted down about half a mile among the sawyers under a falling bank. The canoe struck frequently but did not overset. He at length gained the shore and returned by land to learn the fate of Willard whom he found was yet on the sawyer. It was impossible for him to take the canoe to his relief. Willard at length tied a couple of sticks together which had lodged against the sawyer on which he was and set himself adrift among the sawyers which he fortunately escaped and was taken up about a mile below by Ordway with the canoe; they sustained no loss on this occasion. It was fortunate for Willard that he could swim tolerably well.

Snags and sawyers that break loose during high water can collect into log jams, which the French-Canadian boatmen with the Corps would have called embarrases—”hinderances.”—which could pin a boat broadside against its upstream edge, and possibly cause the current to capsize it.

Sandbars

The bridge pier above was on the South Dakota shore when it was built.

It cannot be said that there was a hierarchy of hazards, but shoals and sandbars where they could run aground and lose control exposed them in turn to potentially deadly driftwood or log jams (embarasses) against which a free-floating boat could be helplessly pinned by the powerful current, or propelled against falling banks, which could capsize or swamp a craft that blundered too near the falling dirt, rocks, and trees.

Riding the current downriver held another chapter of demands and dangers. The pilot or river man had to be unerringly observant, and capable of making quick decisions. The men had to follow his directions precisely and ply their oars strongly and steadily to keep moving slightly ahead of the current, especially when they had to cross (“break”) an eddy line, where the circling currents could swing the boat out of control. It required a sharp eye to read the river and avoid snags, “dead men” and “sawyers” that could puncture the hull.[3]One of the most eloquent explanations of what it meant to be able to read “the face of the water” like a book is to be found in the last three long paragraphs of Mark Twain’s … Continue reading

It was nothing short of miraculous that the barge‘s return trip from Fort Mandan to St. Louis was completed in 43 days at the height of the Missouri River’s spring freshet of 1805, without any reportable accidents that we know of. It is all the more remarkable because it is doubtful that Corporal Warfington had a full complement of oarsmen. What saved him from terminal disaster, beyond his own vigilance and skill as a ship’s captain, may well have been that his pilot and boatman was the French trader Joseph Gravelines, and his crew included at least five of the engagés who had helped the expedition reach the Knife River Villages in 1804–Deschamps, La Jeunesse, Malboeuf, Pineau (Pinaut) and Rivet.[4]Moulton, Journals, 3:227n. Their priceless cargo of scientific specimens, reports, journals, and maps, from which we are privileged to reconstruct many of the early achievements of the Corps of Discovery, is the everlasting–but frequently overlooked–monument to their navigational skill and personal bravery.

Collapsing Banks

There’s a saying among farmers who plant crops in the Missouri River flood plain—”You never know whether you’re going to harvest corn or catfish.” All rivers do it sometimes, in some places, but the unchastened Missouri won countless springtime championships in its time. Still does, as Jim Peterson’s photos prove. Every spring, when the freshet rises the Missouri begins to dance—sashaying from bank to bank through the yielding flood plain. It pushes hard and hurriedly against one bank, while slowing and settling on the other. The dance may last, with diminishing flourishes, until the end of summer.

Mark Twain put it as well as anyone ever has. He speaks here of the Mississippi, but the Missouri deserves his eloquence too: It is “a just and equitable river; it never tumbles one man’s farm overboard without building a new farm just like it for that man’s neighbor. This keeps down hard feelings.”[5]Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 203.

Frequently, the dangers of collapsing banks were worsened by combinations of other impediments—strong wind, swift current, shifting sands, trees and debris precipitated into the river. On one occasion (15 June 1804) the Corps “passed thro a verry bad part of the river, the wost moveing Sands I ever Saw, the Current So Strong that the Ours [oars] and Sales under a Stiff bresse Cld. not Stem it, we wre oblged to use a toe rope, under a bank Constantly falling.”

On the night of 21 September 1804, they barely survived an even worse situation. Clark wrote:

at half past one oClock this morning the Sand bar on which we Camped began to under mind and give way which allarmed the Sergeant on Guard, the motion of the boat awakened me; I get up & by the light of the moon observed that the land had given away both above and below our Camp & was falling in fast. I ordered all hands on as quick as possible & pushed off, we had pushed off but a few minets before the bank under which the Boat & perogus [pirogues] lay give way, which would Certainly have Sunk both Perogues, by the time we made the opsd. Shore our Camp fell in.

Ice

Although the “Little Ice Age” was steadily warming, winters in the northern latitudes still averaged several degrees colder in 1805 than they do now. Today the Missouri River infrequently freezes over solid anywhere, even in northwestern North Dakota. The winds are just as strong, however, sculpting graceful shapes of driven snow among the rumpled edges of an ice jam.

Clark, who accompanied the hunters on a nine-day, 30-mile round trip in early February, explained what it was like to travel on the frozen river. The second day out he broke through the ice and got his feet and legs wet—a very dangerous situation. The third day out, he complained, “walking on uneaven ice has blistered the bottom of my feat, and walking is painfull to me—”

Moreover, conditions on the river changed every few days:

The ice on the parts of the River which was verry rough, as I went down, was Smothe on my return, this is owing to the rise and fall of the water, which takes place every day or two, and Caused by partial thaws, and obstructions in the passage of the water thro the Ice, which frequently attaches itself to the bottom.— the water when riseing forses its way thro the cracks & air holes above the old ice, & in one night becoms a Smothe Surface of ice 4 to 6 Inchs thick,— the river falls & the ice Sink in places with the water and attaches itself to the bottom, and when it again rises to its former hite, frequently leavs a valley of Several feet to Supply with water to bring it on a leavel Surfice.

Hair-raising Hazards

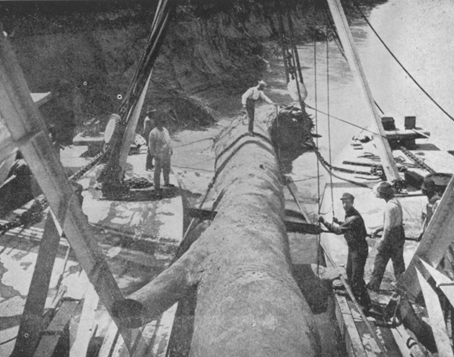

Perhaps the best luck the Corps of Discovery had in the entire two years, four months and ten days it was en route, was that it didn’t suffer any fatal encounters with hazards of the magnitude shown by Chittenden. Considering only as much of the tree trunk as can be seen in the figure (at least one limb has already been sawed off), it was nearly six feet in diameter. If about thirty feet of the butt-end of the trunk is visible, and if the tree is a cottonwood, then this piece of it weighed about five tons—dry! (Cottonwood weighs thirty-eight pounds per dry cubic foot). Imagine the crews of the barge and the two pirogues dealing with snags like this.

At the onset of the steamboat era in the early 1830s it became obvious that, considering the economic investments of the new industry and its importance to citizens living in the Midwest and Northwest, the federal government needed to do something about the kinds of river hazards Lewis and Clark had encountered, beginning with the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Congressional appropriations were first discussed in 1832, and work began in 1838. In that year alone, two snagboats, the Heliopolis and the Archimedes, removed 2,245 snags of all sizes, and trimmed off 1,710 overhanging branches, within the 385 miles between the Mississippi and the vicinity of today’s Kansas City.[6]Hiram Chittenden, History of Early Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1903), II:421.

Notes

| ↑1 | New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 20 July 2024, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c42f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Original from Voyage dans l’intérieur de l’Amérique du Nord, exécuté pendant les années 1832-1833 et 1834, par le prince Maximillien de Wied-Neuwied (Paris: A. Bertrand, 1840-43), Plate 6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 222–25. The original letter is at the Missouri Historical Society Library in St. Louis. (Re-paragraphed here for the reader’s convenience.) |

| ↑3 | One of the most eloquent explanations of what it meant to be able to read “the face of the water” like a book is to be found in the last three long paragraphs of Mark Twain’s memoir, Life on the Mississippi. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, Journals, 3:227n. |

| ↑5 | Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 203. |

| ↑6 | Hiram Chittenden, History of Early Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1903), II:421. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.