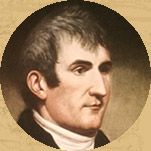

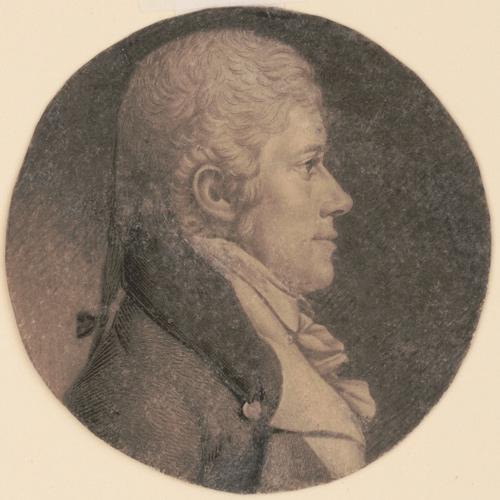

Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin

Self-portrait

Courtesy Collections du Musée des Beaux-arts de Dijon, mba-collections.dijon.fr/ow4/mba/voir.xsp?id=00101-1675&qid=sdx_q1&n=6&e=.

Earlier European Portraiture

Around the middle of the eighteenth century the hobby of a French finance minister named Étienne de Silhouette (1709–1767) initiated a trendy market for paper-cutout “shadow portraits” in black-and-white, or the reverse. They were simple and cheap, like the minister’s economic theories, and reportedly more popular.

The appeal of the new “silhouette” gained impetus in the late 1770s with the creation of a pseudoscience called physiognomy, founded by Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801), and based on the proposition that the shape of one’s profile reflected the owner’s innate moral and behavioral makeup. The next step toward meeting the demand was the technological and representational enhancement of profile portraiture using the camera obscura and other drawing aids such as the pantograph, a German invention dating from 1631, with which anyone could enlarge or reduce any drawing. In 1788, Gilles-Louis Crétien (1754–1811), a cellist in the court orchestra of Louis XVI, invented the physiognotrace, with which even a person without any artistic talent whatsoever could create an accurate profile portrait–in four minutes!

Saint-Mémin in America

In 1793, twenty-three-year-old Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, a royalist refugee from the French Revolution, arrived in America, studied drawing briefly, and taught himself engraving. In 1796, with his own improvement of Crétien’s physiognotrace, he set up his own business as a profile portraitist, quickly gaining fame and fortune as a facile, if not gifted, engraver. For twenty-five dollars a man received the original life-sized drawing, the reduced, engraved copper plate of it, and a dozen copies of the engraving, all accurate with what we might imagine was near-photographic exactitude in terms of facial features, hair styles, and clothing. A woman paid thirty-five dollars, presumably because of the increased details of her hairdo and attire.

In 1798 Saint-Mémin moved to Philadelphia, where he spent the next four years, making some 270 portraits for a well-to-do clientele. An advertisement announced that “the original portrait, [copper] plate and twelve impressions” cost $25 for gentlemen, $35 for ladies; “the portrait without engraving, may be had for 8 dollars.” He enlarged his customer base beginning in 1803 by spending periods of several months successively in other Eastern cities such as Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, and especially Washington, where Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark, were among his sitters, as well as a number of the Plains Indians who visited the President there between 1804 and 1807, including the Mandan chief Sheheke (Big White) and Yellow Corn.

Altogether, in the years between 1798 and 1814, when he returned to France, Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin turned out more than a thousand life-sized chalk drawings, watercolors, and small copperplate portraits that comprise a catalog of many of the most important personages in America during those years.[1]The largest of the copperplate engravings were 2 5/8 inches high by 2 3/4 inches inches in width. Later in life, writing of that luminous phase of his career, he wrote:

The creation of my little engravings is so much my own work that I was obliged to be at the same time draughtsman and engraver, builder of pantograph, physionotrace and small-sized press, manufacturer of roulettes and other instruments necessary to engraving, brayer of my ink, and, furthermore, my own printer.

For my ability in the drawing phase of art I make no claims, since I made use of an instrument in order to obtain the most essential features, and since, if there is any merit in the delicacy and studied exactness of the likeness, the draughtsman owes his ability, so entirely independent of his efforts, to providence.[2]Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 198.

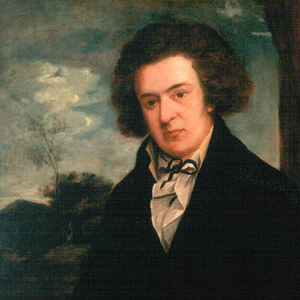

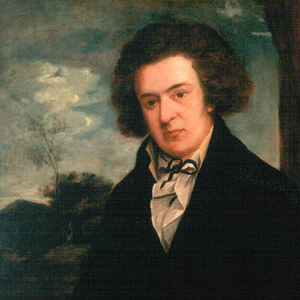

In 1802, Benjamin Smith Barton‘s older brother, William, asserted that Saint-Mémin’s profiles were strikingly true-to-life.[3]See “Federal Profiles, Saint-Mémin in America,” at http://educate.si.edu/migrations/portrait/npg.html. p. 2. In 1969 historian Paul Cutright concluded, however, that Charles Willson Peale‘s oil paintings “probably come closer to portraying accurately the features of the two explorers than any other likeness extant.”[4]Paul R. Cutright, “Lewis & Clark: Portraits and Portraitists,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, XIX, 2 (April 1969), p. 39. Barton’s judgment would seem to be the more reliable, inasmuch as he was a contemporary of the two captains. However, latter image has been more frequently reproduced than Saint-Mémin’s profile, especially with the approach of the expedition’s bicentennial, and so there appears to be a prejudice in favor of Peale’s painting.

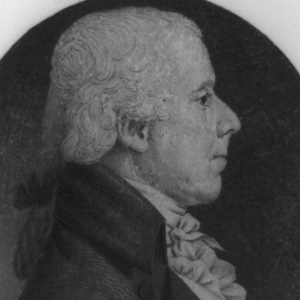

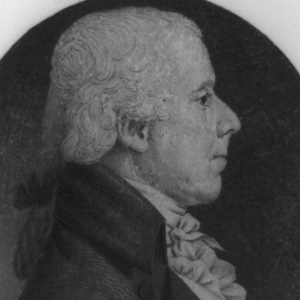

Meriwether Lewis (1803?)

Portrait by Charles Saint-Mémin

Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

Lewis’s Ponytail

In May 1801, a month after Lewis began work as President Jefferson’s private secretary, Brigadier General James Wilkinson, the commanding officer of the U.S. Army, directed that officers and enlisted men were to cut off their traditional pigtails and ponytails: “For the accommodation, comfort & health of the Troops the hair is to be cropped without exception, & the general will give the example.”

Saint-Mémin produced two profiles of Lewis, one probably in 1802, the other (above) in 1803. Either the captain had been exempted from the new regulation because of his inactive status, or else he defied the general’s order as a political gesture.

It may be that Lewis got his GI haircut before heading for the wilderness. In any case, it was gone when Peale painted his portrait in 1807.[5]Arlen J. Large, “Captain Lewis Gets a Haircut,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 23, No. 3 (August 1997), 14–17. His hairstyle then was known as a “Brutus,” after the Roman hero of the First Century B.C.

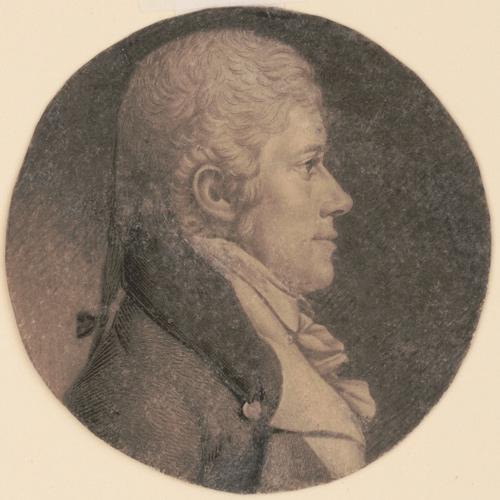

Peale v. Saint-Mémin

Judge for yourself. Compare Saint-Mémin’s and Peale’s portraits of Lewis and Clark:

Featured Artwork

The Osage Delegations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

They were “certainly the most gigantic men we have ever seen,” Jefferson wrote on 12 July 1804. A dozen Osage men and two boys had arrived in Washington City the previous day, escorted by Pierre Chouteau.

June 24, 1803

Expected timeline

In Washington City, Thomas Jefferson tells Benjamin Rush that the Western Expedition will leave Fort Kaskaskia the first of September. In Dover, Delaware, Thomas Rodney accepts two Federal appointments.

Portraits of William Clark

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Four portraits and one statue by five different artists show a diverse interpretation of the likeness of William Clark.

May 24, 1803

Conference with Dickerson

While preparing for the expedition, Meriwether Lewis enjoys a small network of influential friends and mentors in Philadelphia. According to Mahlon Dickerson, the two hold a conference on this day.

Important for the history of the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, its first plant specimens were consigned to Barton’s care. Here began the disassembling of the collection, and his promised volume on natural history was never written.

Sheheke’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Sheheke’s diplomatic trip to Washington City and his difficult return home brought down the careers of at least two great leaders—himself, and Meriwether Lewis.

February 20, 1804

Working in St. Louis

Based on his letter of 18 February, Lewis likely follows through on his promise to join Clark in St. Louis today. There, he helps Pierre Chouteau organize an Osage delegation bound for Washington City.

Cameahwait and some of his people agreed to help the Corps of Discovery carry its baggage over the divide. In the early afternoon. “We now dismounted,” wrote Lewis, “and the Chief with much cerimony put tippets about our necks such as they temselves woar.”

Notes

| ↑1 | The largest of the copperplate engravings were 2 5/8 inches high by 2 3/4 inches inches in width. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 198. |

| ↑3 | See “Federal Profiles, Saint-Mémin in America,” at http://educate.si.edu/migrations/portrait/npg.html. p. 2. |

| ↑4 | Paul R. Cutright, “Lewis & Clark: Portraits and Portraitists,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, XIX, 2 (April 1969), p. 39. |

| ↑5 | Arlen J. Large, “Captain Lewis Gets a Haircut,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 23, No. 3 (August 1997), 14–17. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.